‘Everyone has a theory’: The terrifying serial killer who killed at least nine women - and got away with it

Scores of unsolved crimes have flown under the radar across America for years. Sheila Flynn chronicles the weirdest hair-raising cases

No one connected the dots when the women first started disappearing.

It was 1988 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a busy seaport full of working-class families who tended to grow up, buy homes and stay in the area. Not unusually for a port, particularly in the ’80s, the small New England city was grappling with drugs.

So it took a little while, as young woman upon young woman turned up dead – most of them addicts, prostitutes or both – for the cops to notice a pattern.

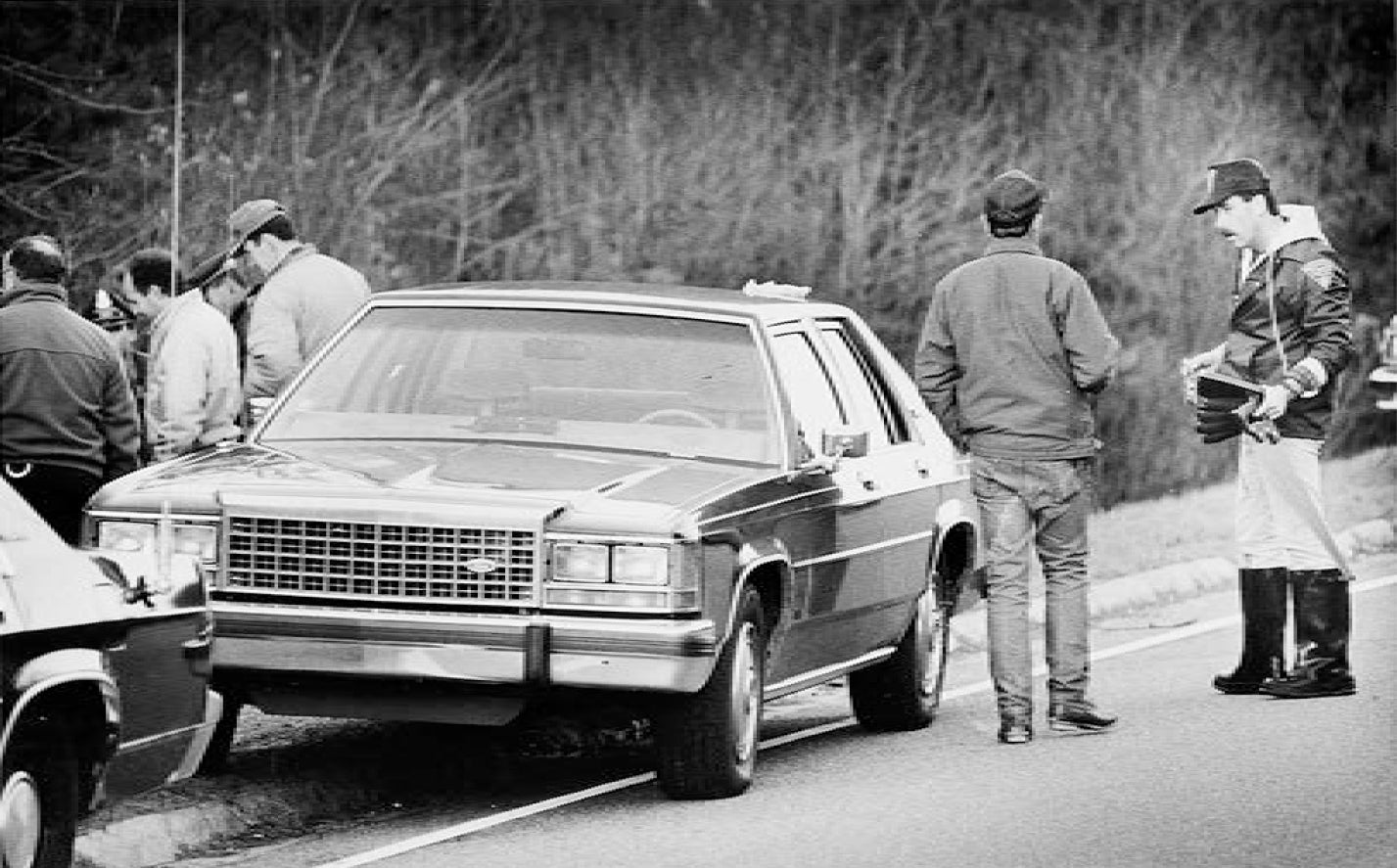

Once they did, however, it became apparent that New Bedford was dealing with a serial killer, one who preyed upon the vulnerable, possibly used a badge and tended to dump bodies near the highway or major roads.

And, after murdering what is believed to be at least 11 women, that killer has never been found.

“Some of the theories are that he’s in jail, or he died, and that’s why he stopped, or he moved away and is maybe killing someplace else,” author Maureen Boyle, a professor who covered the cases as a young journalist, tells The Independent. She adds that the lack of answers constitutes “the most frustrating thing for everyone” – and a latent fear.

Ms Boyle, who wrote a 2017 book about the unsolved murders titled Shallow Graves: The Hunt for the New Bedford Highway Serial Killer, says that multiple theories abound regarding the killings – and the size of the suspect pool is “frightening”.

“You have to step back and realise: Oh my god, there are so many people who could be capable of doing this,” she says. “It really is terrifying.”

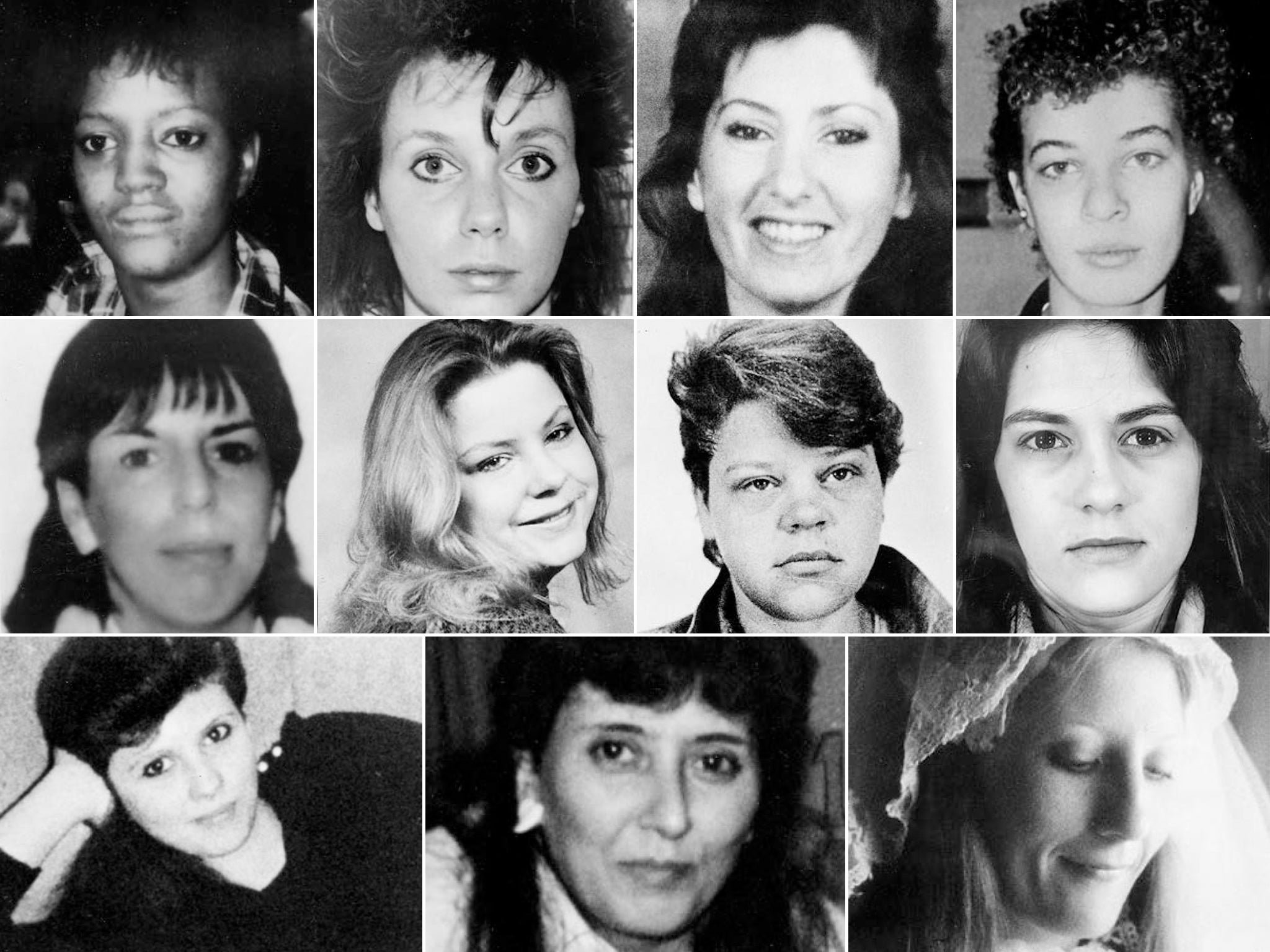

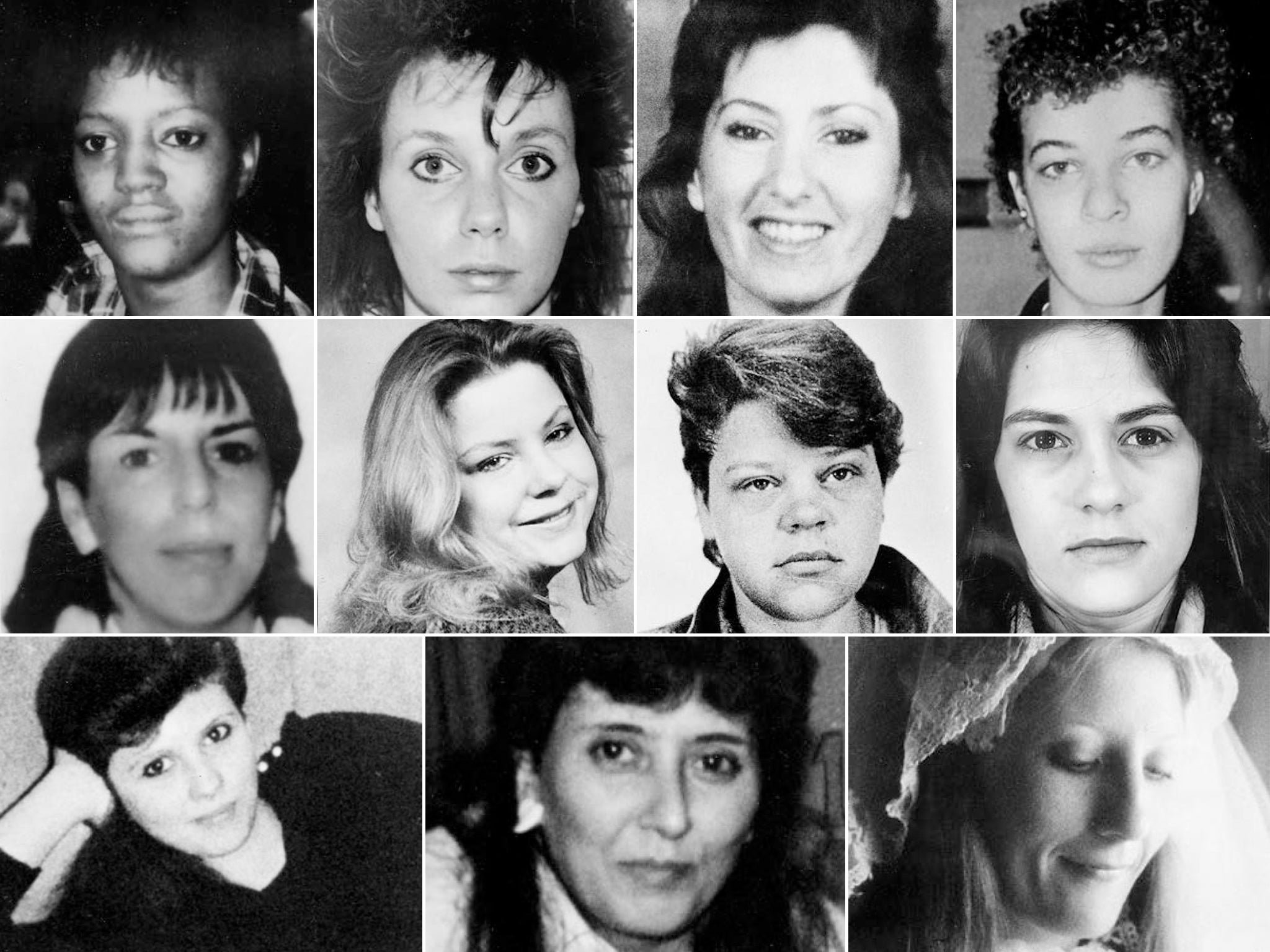

The unrecognisable remains of the first known victim, Debra Medeiros, were discovered in July 1988 by a passing motorist near northbound Route 140 in Freetown, Massachusetts. Within weeks, another woman‘s body materialised; mother-of-two Nancy Lee Paiva had been reported missing by her boyfriend and, while her body was found near I-195, it was only identified months later.

In the meantime, more victims began turning up either missing or dead. There was Mary Rose Santos, 26, also a mother; Sandra Botelho, who left home without a trace on 11 August 1988; Dawn Mendes, 25, who went missing on 4 September; Cape Cod woman Rochelle Dopierala, 28; Debroh Lynn McConnell, 25; and New Bedford teen Christina Monteiro. Debra Greenlaw DeMello, 35, was found dead after walking away from a work-release programme; the body of Robbin Rhodes was found in March 1989.

The bodies of Ms Monteiro, 19, and Marilyn Roberts, 34, have never been found but are presumed to have fallen prey to the same killer. The victims left behind a total of 15 children between them.

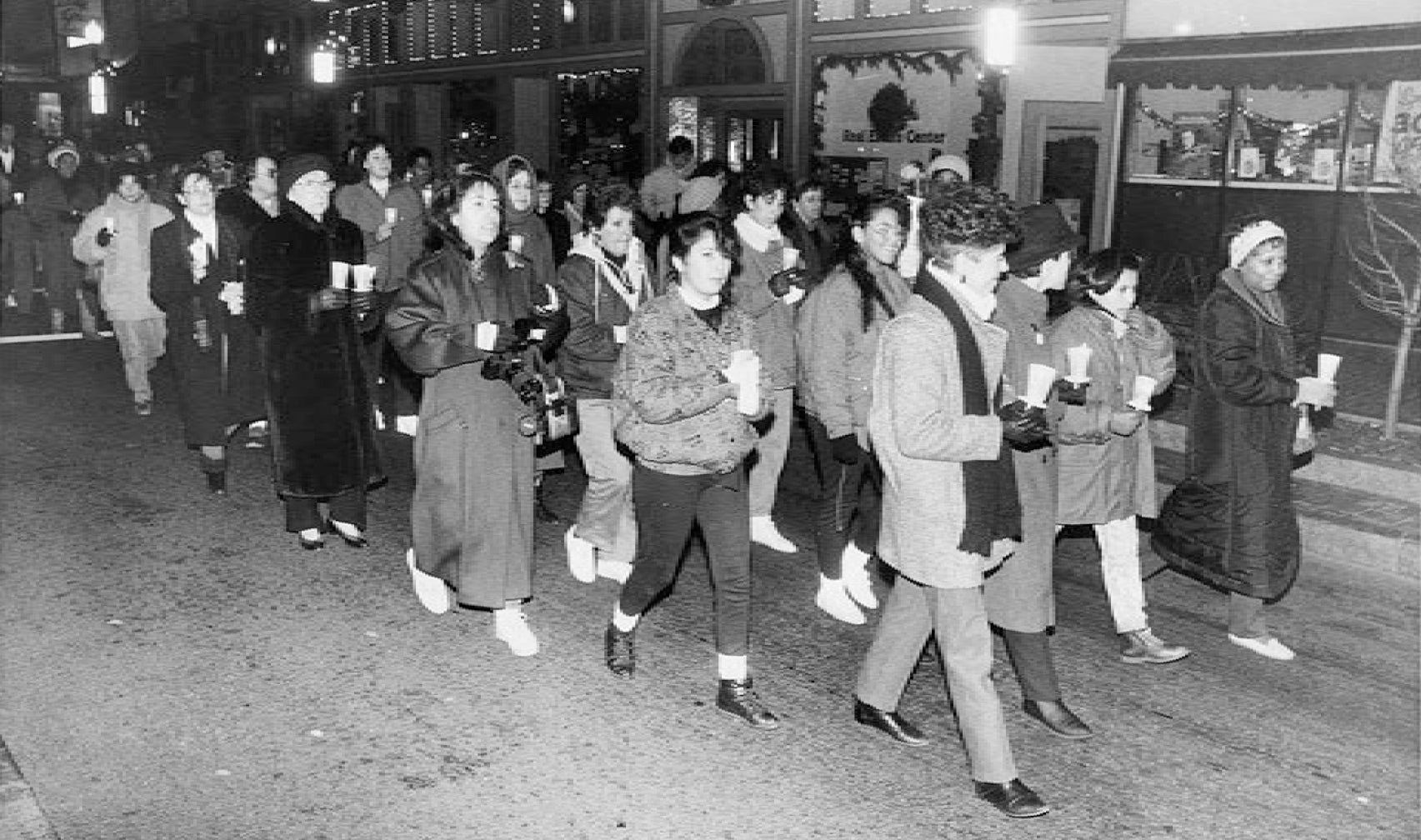

New Bedford is heavily populated by people who emigrated from Portugal and their descendants, many of whom work in the fishing industry; to this day, a Portuguese-language radio station exists in the region. And many of the women came from that tight-knit community, which was horrified not only by the murders and disappearances but by the drug problems they hoped would one day be resolved.

“These are not just women who were found dead,” Ms Boyle tells The Independent. “These were women who ... had families, who were missed.”

She adds: “These were not throwaway people. These were people that were loved, and these were people that had a past before drugs – and they were robbed of the future that they could have had after drugs because someone preyed on them because they were vulnerable ... to this day, the families just always wonder: Who is it? Because everyone has a theory.”

The first person with a theory was a local police officer who noticed the similarities in the young women’s backgrounds. New Bedford Police Detective John Dextradeur might not have been able to immediately identify a culprit, but he guessed there was a serial offender responsible – and convinced the higher-ups to convene a task force months after the first body was found.

It wasn’t long before investigators identified more than a few potential suspects.

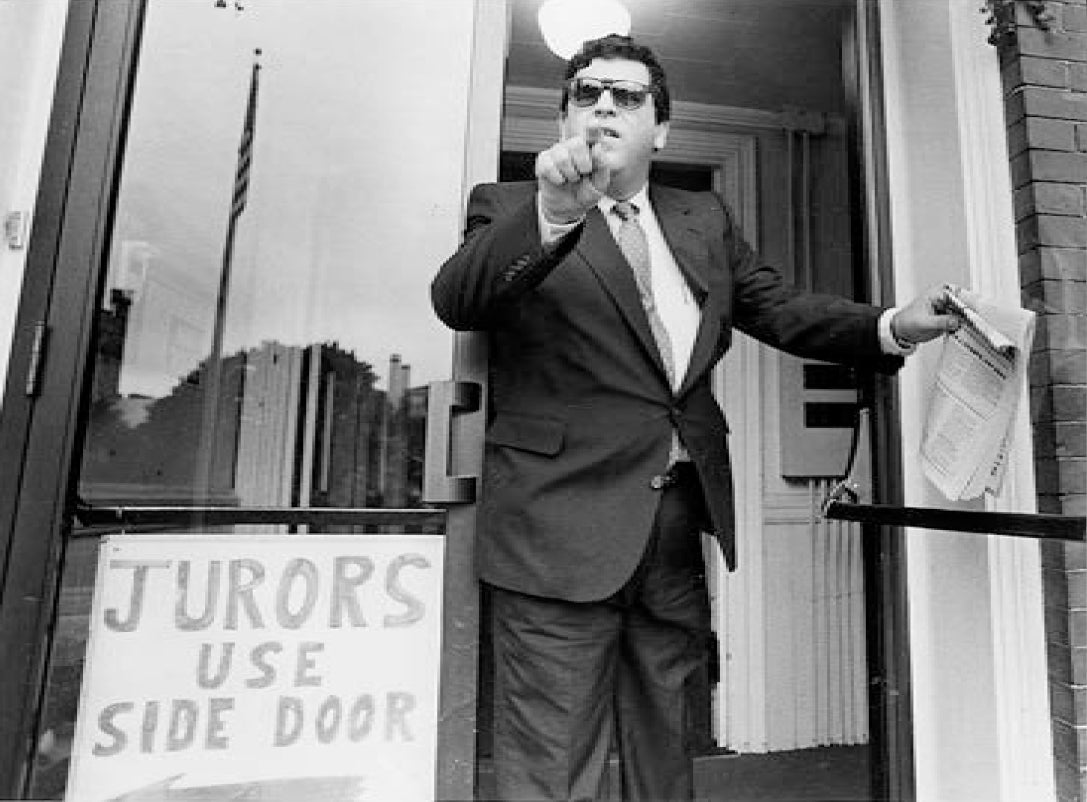

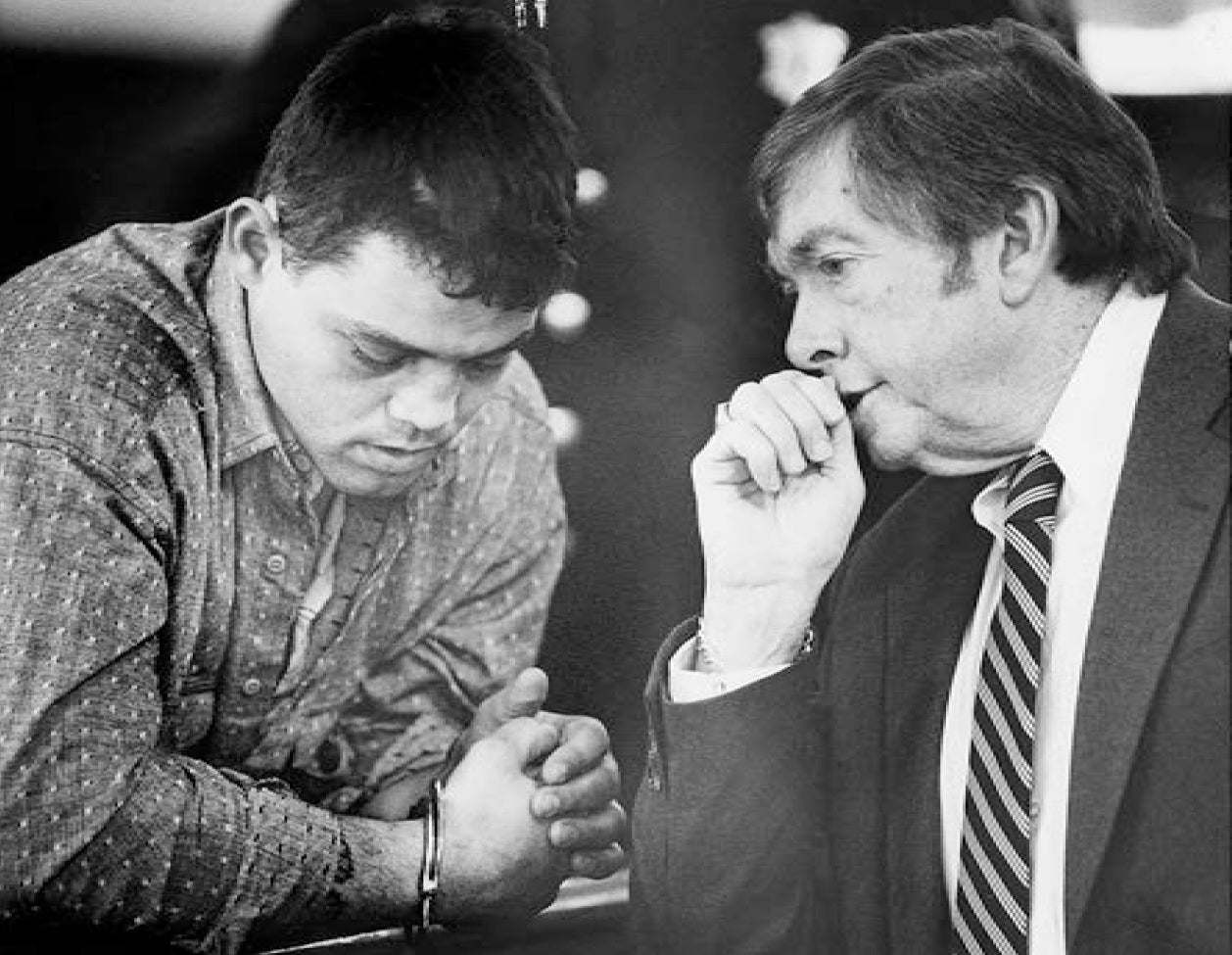

A local lawyer with connections to several of the victims piqued the continued interest of detectives. Kenneth Ponte had represented Ms Santos, worked with Ms Paiva, allegedly dated Ms Rhodes and had at one point hosted Ms Dopierala; on top of that, Ms Mendes had reportedly been seen at his home, too.

He’d been a heroin addict himself before studying law, passing the bar and even earning a deputy sheriff position – including a badge and a gun.

“The girls on the street told stories about his paranoia, how he would bring them to his house, bolt the doors and wouldn’t let them leave. He didn’t seem violent, just really strange,” Ms Boyle wrote in Shallow Graves. But that didn’t stop the girls from going with him, and none of the girls considered pressing any charges. He did, after all, give them coke and didn’t seem interested in sex.”

The timing of his decision to move to Florida, just months after the discovery of the first body, also raised eyebrows. His behaviour down there didn’t help as he ranted about his innocence before being eventually charged with one murder count in the death of Ms Dopierala – a case that was ultimately dropped.

“There wasn’t enough evidence to convict,” Ms Boyle wrote. “There was no ‘smoking gun;’ they had no eyewitness to any of the murders; they had nothing to link Kenny directly to any of the killings.”

The lawyer died in 2010 at the age of 60, with all of these questions still unanswered.

Also in the suspect pool was another New Bedford-area man, Tony DeGrazia, who was feared by the girls on the street for his violence – and recognisable for his flattened nose.

“Most of the girls on the street just knew to stay away from the guy who looked like a boxer,” Ms Boyle wrote.

DeGrazia was interviewed in 1989 but denied killing anyone, though he failed to turn up for a scheduled lie detector test. The testimony of another prostitute named Margaret Medeiros, however, who appeared before a special grand jury, was damning; she said a man named Tony “lunged at my throat” and “tried snapping my neck ... And he told me what he was going to do to me like he did to the other b****es.”

In May 1989, DeGrazia was charged with four counts of rape, six counts of assault and battery, and one count of assault with intent to rape, the charges stemming from attacks on prostitutes during the same time the victims had been killed.

He took his own life in 1991 – again taking any answers to the grave. But he and Ponte were far from the only possible killers on the suspect list.

“There were several other people who came up – and I think what’s more frightening today, when you look back at it, is just how many possible suspects there were – how many people are out there who could have been the killer,” Ms Boyle tells The Independent.

Investigators were shackled by a lack of technology and forensic evidence. DNA testing was still in its infancy; cell phones were essentially nonexistent and even CCTV footage was rare. The case went cold, though everyone in New Bedford still wants answers. The number of victims surprisingly never gathered as much attention as murderers like the Zodiac Killer or Long Island Serial Killer – whose victims, interestingly, began appearing just a few years after the last were discovered in New Bedford, also women dumped on the beach not far from highways, just about four hours south of the Massachusetts crime scenes.

Ms Boyle believes there are reasons that the New Bedford case never really caught the public’s interest.

“It was the [lack of] technology, and it was not in a major city,” says Ms Boyle, an associate professor of communication at Stonehill College.

She adds: “It flew under the radar, because there wasn’t social media; it was pre-internet. So unless you we rereading it in your local paper or seeing it on television, you wouldn’t know anything about the case.”

There’s a cold case unit in New Bedford, and they haven’t given up; neither have relatives of the victims.

Judy DeSantos, the sister of victim Nancy Paiva, told a local CBS affiliate last year that she thinks of her sibling every time she drives by the highway where Nancy’s body was dumped.

“Every time I go by there I’m always looking,” Ms DeSantos said. “Somebody thought she was trash and could dispose of her so easily. It makes me angry.”

Ms Boyle’s book in recent years has also sparked renewed interest to the murders.

“That’s one of the reasons I wrote the book – to refocus attention on the case and document what really happened, because I could see that, as time went by, people were misremembering what happened,” Ms Boyle says.

Locals were “repeating stories like in the children’s telephone game ... in the telling, the stories get changed in the community,” she says.

She won’t name who she thinks might be the actual killer, saying it’s irresponsible as she’s had “so many theories over the years.”

“But there is, in every single community, every single state, unsolved murders – which means that there are killers who got away with murder, killers that are living amongst us. The victims are children, the victims are young women, older women, young men, older men ... It is really frightening what is out there,” she says.

“And as a police reporter, I would see all of that ... there are evil people out there.”