‘Strawberry shortcake’ and Scott Peterson: The bizarre scandal being compared to the Ghislaine Maxwell jury

Experts say the jury system’s Achilles heel is that it relies on the honesty of jurors. Bevan Hurley reports

Richelle Nice broke down in tears as she was asked about the 17 letters she wrote to convicted murderer Scott Peterson after helping send him to death row.

Ms Nice, who was part of the 12-member jury that found Peterson guilty of the 2002 murder of his pregnant wife Laci and their unborn son Conner, was grilled in the witness box in March about whether she had profited from the notorious case, and whether she’d lied on a pre-trial questionnaire.

Peterson’s lawyer Pat Harris alleges Ms Nice is a “stealth juror”, someone who deliberately masks their biases to ensure they are picked for the panel and then ensure a guilty verdict is reached, and are seeking a retrial for one of the most notorious murderers in recent American history.

In the years after Peterson’s conviction, Ms Nice spoke to 20/20 and E! True Hollywood Story, took part in the TV documentary The Murder of Laci Peterson and co-wrote a book with six other panelists We, the Jury: Deciding the Scott Peterson Case.

Over the course of those interviews, details emerged about how Ms Nice had been the victim of domestic violence by an ex-boyfriend, and that she was granted a restraining order against another ex-partner’s girlfriend who tried to kick her door down.

Ms Nice failed to mention either of these experiences during jury selection in the Peterson trial. She hadn’t intentionally left it out, she said while testifying with impunity from prosecution in March, it just hadn’t “crossed her mind”.

Ms Nice, no longer sporting the shock of bright red hair that earned her the nickname “Strawberry Shortcake” during Peterson’s 2004 trial, said she didn’t really consider herself to be a victim of crime.

“I’ve been in many fights and I don’t consider myself a victim,” Ms Nice, now brunette, said.

“It might be different from you or someone else. You might consider yourself a victim, but I don’t.”

Peterson was sentenced to death for murdering Laci and dumping her body in San Francisco Bay and mutilating his unborn son’s foetus. Authorities learned he had been having an affair with another woman Amber Frey, and told her he was a widower. His sentence has since been commuted to life in prison.

Last week, Peterson was back in a California courtroom arguing for a new trial due to Ms Nice’s alleged misconduct.

The judge has 90 days to issue a ruling.

In a case that revolved around violence committed against a pregnant spouse, Ms Nice’s life experiences would have raised immediate red flags had lawyers impanelling the jury been aware of them, Los Angeles-based defense attorney Josh Ritter told The Independent.

“I don’t know how filled with drama her life has been but you would think this is the kind of thing that would stick out to her,” Mr Ritter said.

“It’s hard for people to separate their lives. People are not robots. As much as we tell them they need to put all that aside, it’s very difficult for them to do because their lives are shaped by their experiences.

“This is where the jury system, as good a system as it is, can be deceived.”

Clay Conrad, a partner in the Houston-based lawfirm Looney and Conrad, told The Independent, that a judge had to ask three questions when considering a retrial: was the juror specifically asked about their past, was information intentionally withheld, and did the juror’s background have an impact on their deliberations.

“It would seem to be that there’s a pretty good argument that might have affected her deliberations. If the answer is yes, then chances are he will get a retrial.”

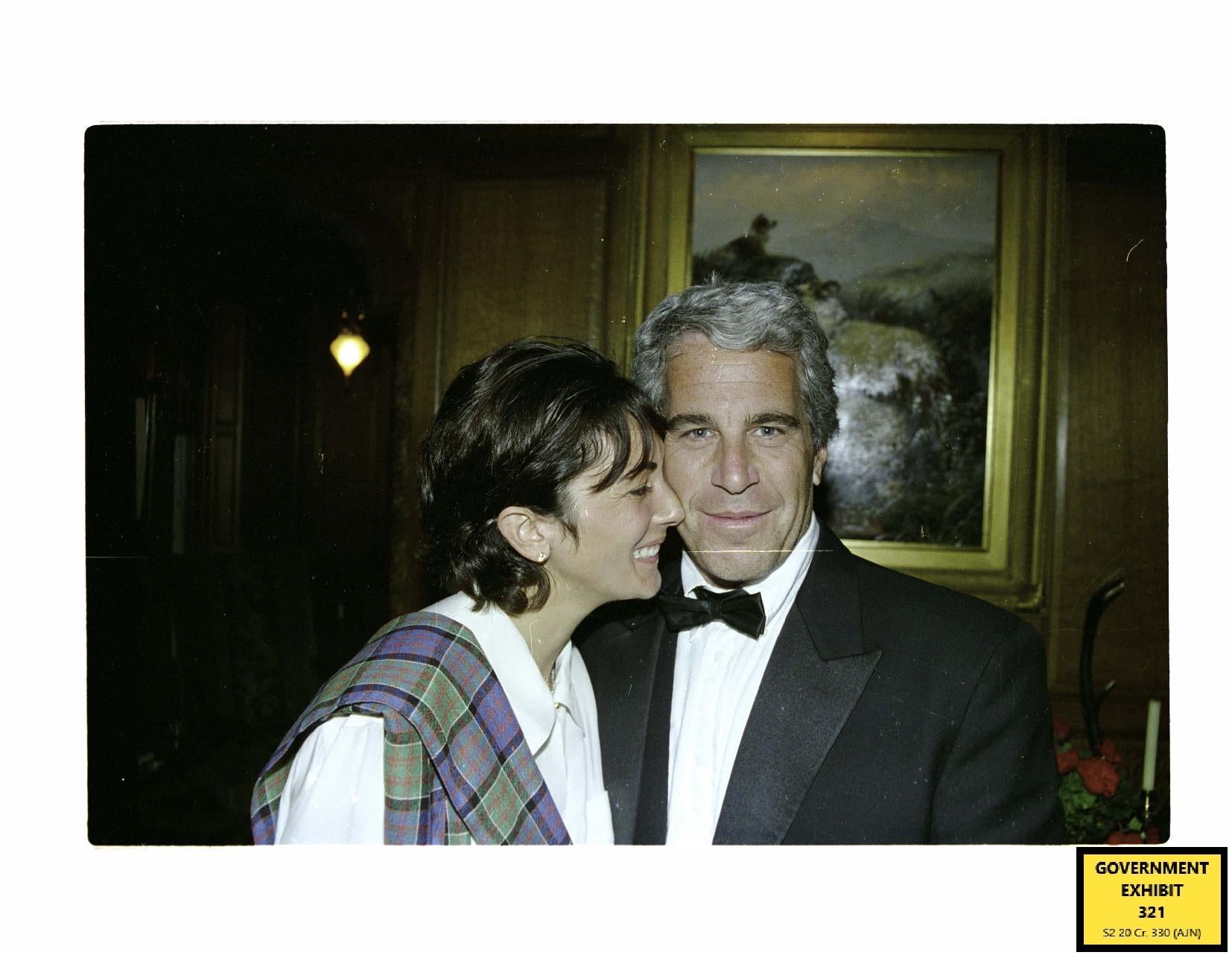

The possible cracks exposed in Peterson’s case bear strong parallels to an effort made by Ghislaine Maxwell’s lawyers to have her convictions for sex-trafficking thrown out, after a juror failed to disclose his history of sexual abuse during a pre-trial survey.

Maxwell’s lawyers claimed Juror 50, known by his first names Scotty David, violated her right to a fair trial after telling by failing to disclose his history of child sexual abuse. He first revealed his experiences of abuse in an interview with The Independent after the trial, and said he had educated other jurors on the historic sexual abuse testimony that were central to the case.

Judge Alison Nathan ultimately denied Maxwell’s bid for a retrial, ruling in April that Scotty David had been a “fair and impartial juror”.

She sentenced Maxwell to 20 years in prison in June.

Mr Ritter told The Independent David’s account of his actions had been problematic, given how carefully vetted information presented to the jury is.

“The parties heavily litigate what is allowed to be presented to the jury - it’s a confined universe of knowledge.

“Whether it’s looking up a location on a map, or some detail on Wikipedia, (jurors) are specifically instructed not to do that.

“In this juror’s case, he’s essentially taking on the role of an expert witness.”

He said if the prosecution had felt it was important for a jury to understand why a victim of sexual abuse may wait a long time before they report it, they would call an expert in that area.

“We don’t want these rogue jury room experts explaining a bunch of stuff that hasn’t been vetted by the lawyers.”

Mr Ritter, a former trial prosecutor who has been involved in dozens of jury selections, said in the vast majority of cases attorneys were not given enough time to properly vet prospective jurors.

“The garden variety defense attorneys don’t have the resources to explore the backgrounds of these folks, and what they’re doing is just spending a few minutes asking questions about their background.”

Without the chance to perform a criminal background check, the jury system still relied on honesty.

“Even when lawyers do have the resources, they cannot get to the depths of the issues if jurors are not willing to engage honestly with the process.

“We don’t hook people up to lie detectors.”

Mr Conrad told The Independent rebellious juries had a storied place in US legal history. He cited examples such as racist charges historically laid against African-Americans, controversial cases during the Prohibition and Civil Rights eras, and says jurors also helped bring cases of spousal abuse to justice during periods when lawmakers looked the other way.

“Cops have discretion to say that’s not worth my time. Prosecutors have discretion, judges have discretion.

“The jury, which actually represents the people, shouldn’t they have discretion as well to say ‘no that’s not how we want our laws used for’?” said Mr Conrad, whose 1998 book Jury Nullification examined the doctrine of jury independence.

In certain circumstances a jury could decide that a law was being unjustly applied, and acquit a defendant who may have otherwise appear to be guilty.

“The people are supposed to be a bit skeptical of the government, and looking over its shoulder, and that is what the jury is supposed to provide, a look at what the government is doing, to whom and why.”

But that would not apply to jurors deliberately withholding or lying about their personal circumstances, he said.

Stealth jurors have been cited dozens of times by defense lawyers hoping to get a conviction overturned on appeal.

After Martha Stewart was convicted of insider trading in 2004, juror Chapple Hartridge gave several media interviews claiming the TV personality’s conviction was a “victory for the little guy who loses money in the markets because of these types of transactions”.

Stewart’s lawyers used the comments to argue unsuccessfully that the verdict was tainted by the juror having an alleged motive to convict.

The plot of John Grisham’s 1996 novel The Runaway Jury followed the efforts of a fictional stealth juror who planted himself on a civil jury which awarded a record damages award against a tobacco company.

Josh Ritter told The Independent jurors were unlikely to ever be prevented from giving interviews or writing books about their own experiences, as those rights are preserved under the 1st Amendment.

However, dreams of writing a Grisham-esque blockbuster could become a “sticky issue” if jurors are already making those calculations before the trial.

He said it appeared some of the jurors in the Scott Peterson trial may have had it in their heads they were “going to hit a jackpot moment”.

Meanwhile, while taking the stand in March in San Mateo, California, Ms Nice was asked about one of the more than dozen letters she wrote to Peterson while he was on death row.

In one, Ms Nice wrote that she was upset how “others got rich” after the trial.

When asked by Peterson’s lawyer about wanting to make money from the trial, Ms Nice said shot back: “I didn’t get rich!”