The fight to end juvenile life sentences without parole – which only happen in America

The US is the only place in the world that sentences kids to prison for life, but that could end this decade if trends continue, Josh Marcus reports

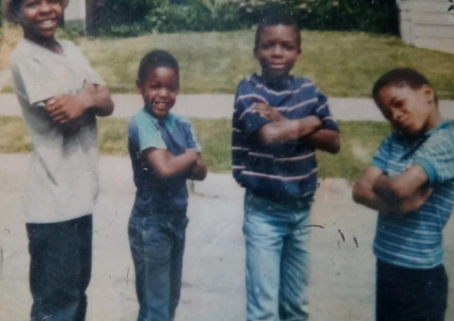

Lorenzo Harrell, 46, says he owes society a debt he can never repay, after committing a homicide aged 17 during a dispute in the drug world of 1990s Detroit.

“He was in the same game I was in, the drug game. I didn’t even know the guy,” Mr Harrell said. “Every day I wake up, I pray for his family. I’ve been doing this for 20 years now.”

Until recently, however, it was a debt he was unable to make good on, unable to turn into something positive for the community. He went to prison in 1993, when he was a teenager, sentenced to juvenile life without parole (JLWOP). It seemed like the end of the line.

He didn’t know such a punishment existed until he was in court, but the criminal justice system was familiar. The son of a drug addicted father and an alcoholic mother, Mr Harrell was first arrested at age nine, describing himself as the “typical, all-American, impoverished Black teen.”

“I was primarily raised in the streets by the people I looked up to, which were the drug dealers and so forth,” he said.

By the time he made it to adult prison, he recognised a lot of the teens and young men around him. They knew each other from juvenile jail. He accepted his fate and focused on trying to survive the “predator and prey” world of prison violence. Healing those he hurt, healing himself, was far from his mind.

Eventually, a 1997 visit from his daughter inspired him to change things, quit using drugs, and try to better himself. He joined a training programme to learn how to become a braille translator, one of the options on offer. He didn’t have a personal connection to the visually impaired, but he thought working with braille seemed like a good way to do something positive.

“From that point on I started working on my life, it didn’t matter that my sentence was life without parole, I just wanted to be the best that I could be in that situation,” he said.

A pair of Supreme Court decisions gave him a chance to do one better. In 2019, after growing from a child to a man during nearly three decades in prison, the growing legal and legislative trend to abolish juvenile life without parole allowed him to be resentenced and eventually released.

Now, he works as a braille translator and an assistant in the state appellate defence office in the Detroit area, and works on criminal justice reform. It’s the end of a long road for Mr Harrell, who was once one of the roughly 1,500 to 2,500 children at a given time sentenced to juvenile life without parole.

America is the only nation in the world that allows children to be sentenced to life in prison, and if a group of reformers have their way, Michigan will be the next in a growing movement of states to abolish the punishment. If they’re successful, it will mean that a majority of US states have outlawed the punishment, an inflection point in US criminal justice history.

Things looked very different ago. In 2012, all but five states allowed kids to get life sentences without parole. Then, came Miller v. Alabama (2012) and Montgomery v Louisiana (2016). The former found that nearly all juvenile life sentences without parole were unconstitutional, and that every mandatory sentence of this type was prohibited. The latter applied these principles retroactively to older cases. It was a major moment, as Justice Kennedy wrote in Montgomery, recognising “children are constitutionally different from adults in their level of culpability.”

Now, 25 states and the District of Columbia have abolished juvenile life without parole, and another seven have no one currently serving such a sentence.

“There’s a reason why we don’t let kids get married, serve on juries, serve in the military. We won’t let a kid sign a contract. We won’t let ‘em buy tobacco,” Preston Shipp, senior policy counsel at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth (CFSY) advocacy group, told The Independent.

“Kids’ brains are not fully developed,” he explained. “They lack the ability to appreciate the consequences and risks of their actions. They lack impulse control. They’re not as good at regulating their emotions. Peer pressure exerts so much influence over these kids, so does trauma.”

That’s why the CFSY has joined with other criminal justice groups, as well as a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers, to push for the end of juvenile life without parole in Michigan, the state with the largest population of juvenile lifers in the country.

This year, lawmakers began pushing to make it so children under 18 can only get a maximum sentence of 60 years in prison, and are eligible for parole review after 10 years inside.

“All individuals should be held accountable for their actions,” state senator Michael MacDonald, one of the Republican sponsors of the initiative, said in January. “Yet, particularly when it comes to youth, the focus should be on rehabilitation and creating a future as a productive member of society rather than simply spending millions of dollars to punish them. These reforms would replace the juvenile life-without-parole laws which have been deemed unconstitutional with responsible outlines for how to deal with minors who have committed crimes.”

Lawmakers are also hoping to pass provisions making it so courts are required to consider a child’s age, immaturity, family environment, life circumstances, and social setting when weighing severe sentences.

It’s a change that couldn’t come soon enough for some serving life sentences in Michigan. Six years after the Montgomery decision in 2016, 80 people eligible for review still haven’t been given a first resentencing hearing, according to CSFY.

There’s also momentum building outside the statehouse.

This year, the Michigan Supreme Court seemed to beat lawmakers to the punch, ruling that courts must consider teens up to age 19 constitutionally different from adults during all sentencing, not just those involving life without parole, noting that youth have “diminished culpability and increased prospects for reform.”

As other criminal justice campaigns around second-chance hiring and automatic record expungement have shown, reforming the prison system and its consequences have shown wide bipartisan appeal, in part because the problems at hand are so glaring.

Reformers hope that the severity of sentencing a child to life in prison, not far off from a death sentence, is enough to move some on moral dimensions. They also believe stats showing that former juvenile lifers have a roughly 1 per cent recidivism rate will convince others that such severe sentences don’t serve much of a public safety purpose.

According to CSFY data, states like Arkansas and Wyoming are paroling 50 per cent or more of their juvenile lifers, suggesting many people are ready for reform.

Other states seem set to join Michigan on this path.

This year, the North Carolina Supreme Court held in a pair of cases concerning people convicted while children, that any sentence longer than 40 years must be parole-eligible, and that a lengthy sentence for a 15-year-old who pleaded guilty to raping and killing his aunt, and wouldn’t be parole eligible for another 45 years, was unconstitutional.

In New Mexico, the senate passed a bill outlawing juvenile life without parole in February, and the state currently has no lifers who entered prison as kids.

Mr Shipp, of CFSY, said this nationwide movement offers a rare chance at non-partisan reform.

“This is not an issue where only the coastal states have done it. When you’ve got the Dakotas on board with Ca, we really really pride ourselves on being able to avoid people feeling like this is a partisan issue,” he said. ”This is an issue where we can bring conservatives and progressives together.”

Mr Harrell is a believer in giving former juvenile life inmates this second chance.

“I know that everyone has the capacity for change, everyone,” he said, as his daughter could be heard playing in the background of our phone call.

“I see a lot of us juvenile lifers out here,” he continued. “A lot of us are doing wonderful things. You can’t tell me that there’s people who can’t come out there and make a difference in the community. It’s just hard to believe because I see it every day.”