We were sexually assaulted years before Madison Brooks. LSU failed us, too

In the aftermath of Madison Brooks’ alleged rape and death, former Lousiana State University students and sexual assault survivors Samantha Brennan and Elisabeth Andries tell Andrea Blanco how the school has failed to address rape culture

Seven years before Madison Brooks was allegedly raped and left to her fate in the middle of a roadway, Samantha Brennan also got in the car with a stranger.

Ms Brennan, then 19, was a student at Lousiana State University and had been out drinking before she lost consciousness inside the vehicle of a football player at the college, she told The Independent. Soon, pictures of her partially naked body began circulating in student circles and LSU’s football recruiting office, where she worked.

“We were both underage drinking at a bar in Tigerland, both met a stranger that night, got in a vehicle with them,” Ms Brennan said of the eerie similarities between her assault and what allegedly happened to Brooks. “It was just unfortunate that her night ended up the way that it did.”

After her assault, Ms Brennan woke up at her apartment, with little memory of what had happened the night before. Brooks saw a much worse fate, having been dropped off on a dark road in Baton Rouge, where she was fatally struck by a car.

Lawyers for Brooks’ accused rapists have since denied test results showing her blood alcohol level was four times the legal driving limit, pointed the finger at her for following the suspects to a parking lot, and claimed that “she wouldn’t have complained at all” about the alleged assault if she were still alive. Meanwhile, a statement by LSU decried underage drinking but largely downplayed the much bigger issue of rape.

That type of victim blaming is all too familiar for both Ms Brennan and fellow LSU alum Elisabeth Andries, 24, who went through a re-traumatising process while filing a Title IX complaint with the school after a classmate sexually assaulted her in 2017.

Ms Andries, too, had been drinking. Alcohol, too, became a focal point in the conversation around her attack.

“Everyone breaks the law a little bit in their life, but why does someone have to die like that? She went out drinking at a bar and she died because she was under 21? That makes no sense. It could happen to her at 21 too,” Ms Andries told The Independent about the university’s response to Brooks’ death.

Ms Brennan and Ms Andries are among at least 10 current or former studentsinvolved in an ongoing class action lawsuit against LSU over its handling of Title IX complaints after an audit report found that the university mishandled sexual misconduct allegations for years. The investigation was prompted by a USA Today article published in 2020.

Both women say that for years, LSU has sent a poor message that ultimately perpetuates an endless cycle of injustice for victims and lack of accountability for predators. While Brooks’ death has reignited a crucial conversation, it is up to the university to take the steps that are needed to spark change, they said.

‘You’re not alone, but also, you shouldn’t be here’

Ms Andries lives in France, a country she calls her safe haven. Every so often, she travels to the US for depositions in her litigation with LSU.

She was a freshman in the industrial engineering program when a classmate invited her as his date on a bus trip to New Orleans with his fraternity. She remembers drinking heavily and vomiting before her date began to touch her without consent. Then she blacked out.

While the attack - which was eventually deemed credible by the university - took place more than five years ago, the consequences are still unravelling.

For nearly two years, she did not report the assault. Then, she walked inside a classroom and realised her attacker was there.

Ms Andries said she started having chronic panic attacks and it became unbearable to attend class. Due to her PTSD, some of her absences were accepted by the school, but not all.

She filed a Title IX complaint seeking to obtain a no-contact order and remove her attacker from class. But because he had not contacted her for a year before filing the complaint, Ms Andries was told she had to reach out to him herself and warn him not to contact her,according to emails reviewed by The Independent.

The Title IX office failed to promptly communicate with Ms Andries while she continued to miss class, she said. Some teachers made accommodations for her after she explained her situation, but the Title IX office told her “there was nothing they could do” about removing her attacker from her classes.

Ms Andries said a female employee told her that she was the one who had to figure out how to arrange her classes that didn’t coincide with her attacker’s because she “was the uncomfortable one.”

Over the course of the Title IX investigation, Ms Andries recalled being asked by a male employee whether she had consumed weed, cocaine, heroin or other substances on the night of the assault that could have possibly affected her recollection of events.

“When he was asking me about what drug I got, I got enraged,” Ms Andries said. “I was like, are you going to ask me what I’m wearing next? Is that what you want to know? It was a Bernie Sanders costume in case you’re wondering.”

“I looked disgusting because I was dressed as an old man. It just felt like [it was] victim blaming.”

The student Ms Andries accused was ultimately found “responsible” for the assault, emails reviewed by The Independent show.

The perpetrator first received a deferred suspension — meaning that he would only be suspended if he was found responsible for another complaint or had another disciplinary issue — before another victim appealed and he was briefly suspended from school.

Ms Andries, who participated in the appeal panel, said she encountered him at a football game during his suspension period.

On the same day that USA Today published an article on allegations by Ms Andries and Ms Brennan, the former said she received an email from LSU staff telling her that the man who assaulted her would return to class the following semester. By then, the pandemic had started and online classes replaced in-person lectures.

Ms Brennan and Ms Andries say that many of the women currently in the lawsuit have, regrettably, very similar stories.

“I think LSU has sent a pretty poor message to students,” Ms Brennan said. “Many of the other girls that I’m currently in the lawsuit with … their assailants were LSU students and nothing was done.”

“Some of the girls are still students, so the girls in our lawsuit have spanned from, I think 10 years ago up until pretty recently. Nothing has been done. How are students going to feel comfortable trying to report and go forward with it?” she added.

An LSU spokesperson told The Independent that “significant improvements” have been made since the scandal broke in 2020. The university said that its Title IX office has been revamped and “continues to review processes and monitor any potential barriers to reporting.”

“The university has built a robust Office of Civil Rights & Title IX with 12 staff members on the main campus,” the statement read. “The creation of this office and its increased staffing help move complaints through the process more quickly and efficiently.”

Some of the resources offered to students, the spokesperson said, are based on their housing, academic, and mental and physical health needs.

But Ms Brennan said that certain decisions, such as LSU ending its partnership with the Sexual Trauma and Response (STAR) nonprofit, send a loud message.

The group offered training sessions on workplace harassment, sexual assault and how to deal with trauma. The university had hired STAR in 2021 following a damning audit report that revealed issues with Title IX complaints, the Louisiana Illuminator reported.

When asked why the contract with STAR was not renewed, the university said that the plan “was always to grow our internal Title IX office, and to be able to [independently] provide all the services and trainings.”

“Now that we have accomplished that, we no longer need to contract with an outside organization for these services,” LSU said.

Despite LSU’s position, STAR president Racheal Hebert said in an interview with the Illuminator last year that she worried the program was scrapped too soon, with the university potentially not recognizing sexual violence as the pressing public health issue that it is.

“[Every time] a new girl joins the lawsuit, it’s a weird feeling of ‘you’re not alone, but also, you shouldn’t be here,” Ms Andries said.

A trial date for the case was set for 26 June, according to court documents.

‘This is not the time to blame the victim’

The night that Ms Brennan was assaulted, she bought drinks with a fake ID that had her weight off by 40 or 50 pounds and said that she was five inches taller than she really is.

It did not even have her real picture, but she was allowed to buy alcohol.

Her case is not isolated. Tigerland, the area where she was out drinking that day and also where Brooks met her alleged rapists, is notorious for being a dangerous area where minors can easily access alcohol.

Following Brooks’ death, LSU President William Tate vowed to investigate businesses that allow underage drinking in a statement to students. He did not make mention of the sexual assault, only saying that “what happened to her was evil, and our legal system will parcel out justice.”

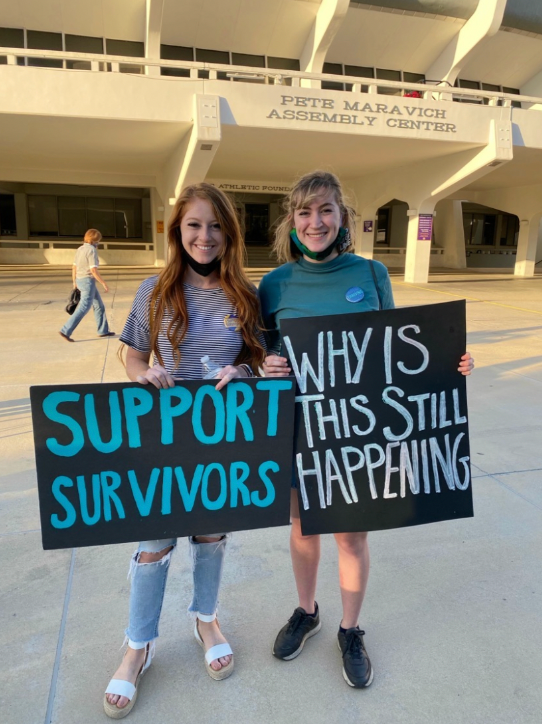

Students have said the message falls short of condemning the issue of sexual assault and demanded that Mr Tate use his “energy to fix the sexual violence our community faces instead of using alcohol as a scapegoat.”

“While students are grieving the loss of our peer and fearing for our safety and well-being, your administration directs its attention to the underage consumption of alcohol. This response is inexcusable,” the group LSU College Democrats said in a statement.

When reached by The Independent, an LSU spokesperson said that Mr Tate’s statement addressed “perpetrators and establishments that enable them to weaponize alcohol against our students.”

“Coming down hard on bars that are serving minors in our community is one of many strategies the President is proposing,” the statement read.

Rhetoric about the role of alcohol on the night that Brooks died has also emerged in social media, but Ms Brennan warns that debate cannot be used to justify the unjustifiable.

“There is something to say about underage drinking,” Ms Brennan said. “But that should not be the highlight. [Tigerland] is such a dangerous area, people are easy to be preyed on, but LSU has had a pretty bad run in history with sexual assaults and rape.”

“They could push harder and do more and take more action to try to advocate and really enlighten the student body ... Being in a similar situation when I was 19 ... nobody asks to be taken advantage of, and nobody asks to be left on the side of the road.”

Attorneys for Brooks’ alleged attackers —Casen Carver, 18, Kaivon Deondre Washington, 18, Everett Lee, 28, and an unnamed 17-year-old — held a press conference saying Brooks “wouldn’t have complained” about the alleged rape “if she was alive”.

That hypothetical scenario, Ms Brennan said, would have not been an indicator of whether a crime was committed by the suspects.

“I never told my parents what happened to me. I filed that police report and I dropped out of school and I never told them why it was. Not until when all of this resurfaced,” Ms Brennan said. “I tried to tell myself that it wasn’t my fault and that I didn’t ask for that. And that’s a really tough state.”

The man accused of taking pictures of Ms Brennan’s partially naked body was not disciplined by LSU, nor was he criminally charged in connection with the alleged incident. Ms Brennan said that she was not informed of her right to file a Title IX complaint, and was instead advised to file a police report — but did not press charges.

The university only banned him from the football program after two 2016 rape allegations against the man and three 2020 domestic violence incidents in which he was involved resurfaced in the 2021 audit report, according to ESPN.

Ms Andries also did not file a police report against her attacker, and said LSU never advised her to.

Brooks’ impact on the LSU community

As part of the investigation into the circumstances leading up to Brooks’ death, four men have been charged.

On 22 February, a state grand jury upgraded charges against the 17-year-old suspect Desmond Carter, 17, so that he will now be tried as an adult.

The bar where Brooks met them had its liquor license removed, but denied serving her alcohol.

Her family has created a foundation to “provide financial help to those in need, advocate for the safety of young adults and spread awareness for the gift of organ donation” — Brooks donated her heart and kidney.

“Really the goal of Madi’s mom is to never have this happen again, to never have any family feel the kind of pain she is feeling right now,” the family’s attorney Kerry Miller told WAFB last week.

And students who never met her but have been touched by her story are doing everything in their power to make sure it is not repeated.

Alisha Ortolano, a pre-vet student, created an “LSU girls’ ride” GroupMe so young women can offer and request rides if they find themselves in an unsafe situation and have no way to get home. According to Ms Ortolano, more than 900 girls have already joined.

“There have already been so many girls who have been picked up by other girls in the group chat,” Ms Ortolano told The Independent. “They’ve said that they’ve made friends through this and feel so much safer ... I’m hoping LSU implements a lot more safety features that are accessible to all, male and female.”

Ms Ortolano said that another initiative, which entails having groups of female “sober monitors” take shifts in Tigerland to ensure no one is taken advantage of, is also in the works.

“I am hoping girls at other universities take the initiative to start something like this on their own campus,” she said. “No girl should ever feel alone or feel like they’re in an uncomfortable situation with no way out.”