From distress to destruction: The unheeded warnings before a former Army reservist’s deadly mass shooting in Maine

Friends and family tried to get help for months for Maine Army reservist Robert R. Card II, who was clearly suffering from deteriorating mental health before he killed 18 people in Lewiston mass shootings last October. A new Army report details how Card and his family were failed repeatedly by civilian and military resources – culminating in the devastation of countless lives, writes Sheila Flynn

Robert R. Card II had been hearing voices and talking about “shooting up” places for months when he walked out of a New York psychiatric facility last summer. He’d been sent there by his Army Reserve superiors after concerning behavior at annual training; this followed almost half a year of escalating instability that repeatedly prompted his close friends and family to seek help.

They hit walls at every turn – and Card’s inexplicable discharge last summer would be no different. He spotted a friend’s car through a window and seemingly walked out without medical instructions for his ride back to Maine, complaining on the journey that he’d been misdiagnosed by a team of doctors who noted paranoia, psychosis and homicidal ideation.

Card’s doctors didn’t talk to his commanders. Those officers mistakenly thought they had no access to his records. Attempts to contact Card for medical follow-ups were abandoned simply because he ignored messages. Even when a close friend texted Card’s superior to warn he feared the truck driver could “snap and commit a mass shooting,” law enforcement visited Card’s home but retreated without engaging him.

Within weeks, the 40-year-old launched an assault on patrons at a Lewiston bar and bowling alley, killing 18 and injuring 13 others before vanishing, armed and dangerous. The 38,000-person city and its environs endured a terrifying two-day lockdown amidst a multi-agency manhunt before Card was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on October 27, 2023.

The catastrophic series of failures leading up to that moment – with virtually everyone but Card’s family dropping the ball – was outlined in a new report released this week by the Army. After interviewing 43 witnesses and gathering 445 exhibits, the report authors laid out in stark, damning terms how communication lapses and other missteps preceded the massacre.

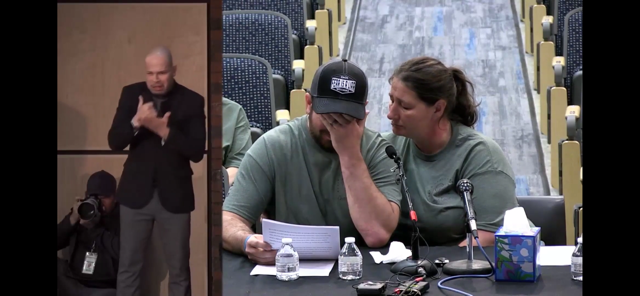

Every failure bolstered the emotional testimony of Card’s friends and family, who spoke in May before an independent commission set up by Maine’s governor. Shaking with sobs at times and frequently pausing for composure, they detailed how messages they left with Card’s superiors went unanswered while attempts to secure help elsewhere faltered, too.

“It’s on all of us to make sure the next time we need to get help for someone, we do better,” Card’s ex-wife, Cara Lamb, told the commission.

That much is certainly evident in the report released this week but dated March 7, which reveals that three Army reserve officers were disciplined for dereliction of duty following Card’s deadly actions. The report not only highlights failures leading up to the rampage but also notes, with an undertone of angered incredulity, how relevant individuals refused to cooperate with the investigation.

The Army hospital Card’s superiors sent him to wouldn’t talk. Neither would the psychiatric facility that released him last August. Even the Maine State Police didn’t furnish requested reports “which included interviews with other witnesses … and other forensic information about the last days of SFC Card’s life,” the Army report complains in its 115 pages.

But the findings within those pages still “paint a very clear picture that there were numerous errors along the path leading up tot this tragedy,” Travis Brennan, a lawyer representing families of the victims said this week.

“There were repeated warning signs that the shooter displayed before the shootings.”

That behavior began at the beginning of last year, according to friends and family of Card, who’d grown up locally and was described by fellow reservists as “kind, friendly, calm and generous.”

“The first time SFC Card complained about hearing people talking about him behind his back occurred in January 2023 … Shemengees Bar and Grille,” the report states, naming the establishment where Card would ultimately open fire on October 25.

Card, who’d suffered long-term hearing problems that didn’t require a waiver for joining the Reserves, also ordered hearing aids around this time; they arrived in March.

While the truck driver endeavored to become accustomed to them, however, he was also more frequently insisting that he overheard people talking about him – calling him a pedophile or other insults. He started worrying people were talking about him online, too, according to the report.

His increasingly volatile behavior and paranoia – including answering the door with a gun – had prompted friends and family to contact local law enforcement by May, detailing at least four concerning instances. They all noted his access to weapons; he’d recently retrieved at between 10-15 guns from a storage spot, the report states.

Army Reserve superiors were aware of concerns when Card attended monthly training in May and June though assumed he was being treated by doctors; his behavior at annual training in July at West Point, however, could not be overlooked.

In addition to exhibiting paranoia, Card was muttering what seemed to be threats, sequestering himself in his room and glaring with a “thousand-yard stare,” according to the report. That prompted the involvement of New York State Police, who interviewed Card and declined to take him into custody but escorted him to Keller Army Community Hospital at West Point.

After an assessment, he was transferred to Four Winds Hospital in Westchester, which had more comprehensive facilities; reasons for his admission included reports of psychosis, paranoia, homicidal ideation and “the patient endorsing having a ‘hit list,’” according to the report.

But Card requested release, prompting a scheduled court hearing for August 2. But Card rescinded his request and the court hearing was cancelled – only for him to be discharged on August 3 and essentially left to his own devices.

“The facts surrounding SFC Card’s discharge are suspect,” the report states.

Upon his return to Maine, Card’s paranoia seemed to increase, and he began accusing more people within his close circle of being against him. When the Sagadahoc Sheriff’s Office checked on him in September – following reports that Card was suffering psychotic episodes and threatening to shoot up military facilities – they heard him moving in the trailer but decided to leave “due to being in a very disadvantageous position.”

Just under six weeks later, Card first walked into Just-In-Time bowling alley, opening fire and killing eight people before driving to nearby Schemengees bar & Grille, where he killed ten more. Terrified locals cowered in their homes as only law enforcement swept the street for two days before Card was found at the recycling corporation that once employed him; he’d taken his own life.

“I defer findings, pending the results of Walter Reed’s evaluation, on whether Four Winds met the standard of care, or whether mental health treatment could have prevented the mass shooting and/or suicide,” the report states. “Based on the testing administered by Four Winds, I believe SFC Card should have remained hospitalized in July/August 2023 rather than being released after a brief 19 days.”

The failures kept coming, however.

“I find a preponderance of evidence that if Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office had fully executed the health and wellness check on SFC Card in September 2023, then the mass shooting and suicide may have been avoided,” the report states … SCSO had the last, best, chance of impacting SFC Card’s actions.”

And the report, despite coming from the Army itself, did not let the Maine reserves off the hook whatsoever.

When investigators asked whether Card’s “command team sought information from Four Winds on SFC Card’s discharge instruction, prognosis, or need for follow-on care,” they were told “that they believed they were not privileged to this medical information … there are no indications the chain of command sought guidance from their serving Legal Advisor or Command Surgeons.

“At the very least, some members of the chain of command should have known of the command exception to HIPAA,” the report states, recommending more training.

The three Army members disciplined (they are not allowed further promotion in the military, ensuring their Army careers are limited) have not been identified, and parts of the report are heavily redacted. A separate report from the Maine governor’s independent commission is expected later this summer. Family members are clamoring for more comprehensive probes into how and why such a tragedy could happen, especially with so very many missed red flags.

Within the Army Reserves, however, Lt Gen. Jody Daniels acknowledged this week the “series of failures by unit leadership” and promised the military would try to do better.

“My heart and soul goes out to all those families, the folks that were witnesses to what happened,” Daniels told reporters. “We’re doing the best that we can in terms of understanding what did transpire, then make changes for the future.”