Will the Idaho college murders become America’s next cold case?

It’s been one month since four Idaho students were brutally murdered, and fears are growing that the case is going cold. Rachel Sharp and Josh Marcus explore a troubling trend in America’s homicide clearance rates - and what happens to the families and communities left without answers

A month has now passed since four University of Idaho students were found brutally murdered in their beds, and police in the small university town of Moscow appear no closer to solving the case.

Not a single arrest has been made. No suspects have been identified. And the murder weapon is nowhere to be found.

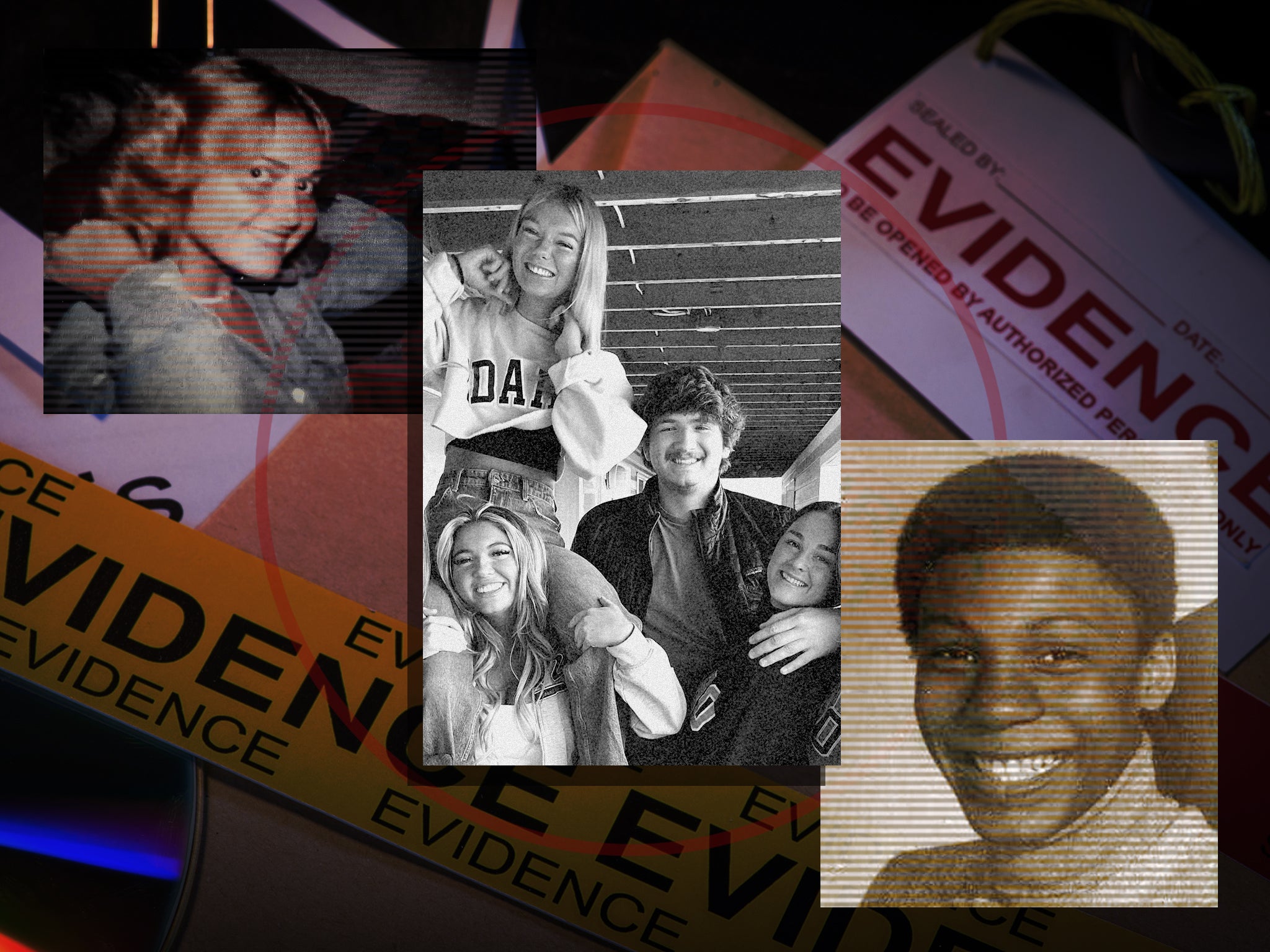

With each day that passes, fears grow that the investigation is going cold and that the mass murderer who violently stabbed Kaylee Goncalves, Madison Mogen, Xana Kernodle and Ethan Chapin to death will continue to walk free.

Confidence in law enforcement has been fraught from the get-go, after Moscow Police initially insisted that there was no ongoing threat to the community.

This claim was dramatically walked back days later, and authorities gave a chilling warning this Saturday urging students, visitors and locals to “stay vigilant” and travel in groups during the college commencement ceremony.

Students and locals previously enjoyed the relative safety of the small college town where many residents didn’t even lock their doors. Now they are arming themselves with guns and securing their homes with deadbolts. Some have upped sticks and left Moscow altogether.

Many have accused officials of bungling the murder investigation, with tensions between law enforcement and the victims’ devastated families now reaching boiling point.

“They’ve messed up a million times,” Goncalves’ father Steve Goncalves told Fox News last week. His family is now considering taking legal action against Moscow Police and are hiring a private investigator to work on the case.

Kernodle’s mother Cara Northington too has hit out at the lack of information about her daughter’s killing, telling NewsNation: “There is so much more that can be done that has not been done.

“They haven’t said anything. I learn more on the news and on TV than what they have said to me.”

Despite confidence waning in the abilities of law enforcement, Moscow Police Chief James Fry has insisted that his department still has a handle on the case.

“This case is not going cold. We have tips coming in, we have investigators out every day interviewing people. We’re still reviewing evidence, we’re still looking at all aspects of this,” he told Fox News.

But the reality is, in America, it’s almost as common for murders to go unsolved as it is for the killer to be caught.

A depressing curve

According to FBI data, just 54 per cent of homicides were cleared through arresting and charging the suspected killers in 2020 – marking the lowest murder clearance rate on record.

Thomas Hargrove, founder and chairman of nonprofit the Murder Accountability Project which tracks unsolved homicides across the US, tells The Independent that this rate likely plunged even further in 2021.

“Unfortunately we’re right on the edge of becoming the first Western nation to allow more murders to go unsolved than they are solved,” he says.

And the longer a case rumbles on, the likelihood of it being solved only diminishes further.

“It’s a depressing curve. Nothing good happens over time in a murder investigation,” he says.

This leaves communities searching for answers that sometimes never come.

‘There’s the feeling that this will never end’

Thirty miles from Moscow in another Idaho town along the Washington border, Gloria Bobertz knows this only too well.

For her family, it’s been 40 years since her cousin Kristina Nelson vanished from Lewiston one night, her body discovered in a canyon 18 months later.

It was 12 September 1982 and Nelson, 21, and her stepsister Brandy Miller, 18, went to buy groceries and do laundry. They were never seen alive again.

Stephen Pearsall, a 35-year-old janitor, also vanished that night, too, after heading to the local theatre where he worked to practice his clarinet. His body has never been found.

In the 18-month period before Nelson and Miller’s bodies were found, Ms Bobertz says she already knew deep down that her cousin was dead.

“I knew she was gone,” she tells The Independent.

“I knew she was not on this earth anymore, it’s a feeling… and when they found her body in March 1984, I remember it exactly – how I was standing in the backyard and what I was wearing.

“I remember it like I left and wasn’t there anymore, like I was back on the cross-country vacation we did together when we were 13.

“It makes you realise that there are monsters out there and it bothered me to know what happened to her as she was such a kind and gentle soul.”

The toll it takes on a family when a loved one is brutally murdered is one thing, she says. But when the murder then goes unsolved, it becomes a double blow to the families left behind – something that is always there no matter how many years go by.

“It’s been 40 years for our family,” she says.

“There’s anger, there’s hopelessness, there’s the feeling that this will never end, that we will never have answers.

“And sometimes you’re so tired of the digging, gathering and looking that you just want to throw in the towel but then if you do that there really will be no answers and no justice.”

Ms Bobertz says “it’s a ripple effect” that “touches each and every person in the family”.

“And the longer time goes on and the case goes unsolved, family members die,” she says.

For Ms Bobertz, getting answers about what happened to her cousin and justice for her murder has become a huge part of her life.

Over the last two decades, she has spent countless hours digging into the case alongside cold case detective Jackie Nichols. She often travels from her home in California to Lewiston to spend weeks at a time working on the case and visiting the place where her cousin was last seen alive.

She also runs a dedicated Facebook group to help gather tips which she then sends onto law enforcement.

Now that she is retired, she is going through the process of training one of her three German shepherds to become a cadaver dog – if not to help in her cousin’s case then to be able to help other families desperate for answers.

In order to stay focused on the case, she says she has to separate the practical side of things from the grief of losing her cousin.

“Over there I’m going to be emotional and over here I’m digging for tips,” she says.

“I’ve conditioned myself but I have moments of total frustration and there are times it does get too emotional and takes you to a very dark place…”

Returning to the theatre where she believes her cousin was killed gives her that push to keep fighting for answers.

“I sit there and I ask, ‘Please tell me where to look and what I need to see’,” she says.

“And usually when I’m there someone comes up to me and gives me a piece of the puzzle or tells me something about them that makes me realise what great people they were – that gives me the drive to keep going.”

Today, many believe the deaths of Nelson, Miller and Pearsall came at the hands of the same local man – a man many also believe to be a serial killer responsible for the unsolved Lewis Clark Valley murders. (One of those murders tragically also involved a University of Idaho student in Moscow.)

Ms Bobertz breaks down in tears as she explains what it would mean to her for her cousin’s case to finally be solved after all of these years.

“A happiness I don’t think I’d ever be able to describe just to know the victims have justice and us families have answers,” she says.

“I think I could finally break down at that point and release all those emotions I’ve had pent up. It would be overwhelming… just to know everyone has answers and justice.”

She hopes that the families of the four students in Moscow won’t have to wait as long to get answers in the case.

“My heart goes out to the families as, as a family member you want to know something is being done, you want answers and justice and right now they’re not getting it,” she says.

The families of those killed aren’t the only ones who suffer when murders go unsolved.

‘You look at everyone and wonder’

In the absence of answers, innocent people often fall under suspicion.

Back in 1980s Lewiston, Pearsall, the janitor who went missing, was considered a suspect for some time.

While he was later ruled out and is now regarded as a third victim of the same attacker, his body is still undiscovered, so some speculation will always remain.

Over the past three weeks in Moscow, several names have been circulating among internet sleuths in Reddit discussions.

While police are keeping much of the investigation under wraps, investigators have tried to slow the rumour mill by debunking theories and confirming that several individuals with ties to the victims – the two surviving roommates, an ex-boyfriend of one of the victims, the so-called “hoodie guy” seen with two of the victims not long before the murders – have been ruled out as suspects.

But that hasn’t stopped their names being made public online and rampant speculation circulating about their possible involvement.

“When a case is unsolved and you have a lack of credible information, you get a disturbing pattern of intense speculation,” Áine Cain, journalist and co-creator of The Murder Sheet podcast, tells The Independent.

“You get accusations against innocent people and basically a cycle that keeps turning where people really focus on the case – and while it can be well-intentioned and helpful, at the same time there can be a lot of speculation and accusations.”

Ms Cain and her husband and business partner Kevin Greenlee have spent years reporting on two infamous cold cases in Indiana.

One is the Burger Chef murders.

It was 17 November 1978 when four young workers aged 16 to 20 vanished from a Burger Chef restaurant in Speedway, Indiana, near the end of their shift.

Two days later, their bodies were found nearby. They were all still dressed in their restaurant uniforms.

To this day, no one has ever been charged with their murders.

The second case is the Delphi murders.

Back on 13 February 2017, best friends Libby German, 14, and Abby Williams, 13, set off on a walk along the Monon High Bridge Trail in Delphi. The next day their bodies were found in a wooded area less than half a mile off the trail.

Before they were killed, Libby had managed to capture a man believed to be their killer on her cellphone. In a chilling video, the man is heard telling them: “Guys… down the hill.”

This October, there was finally a break in that case as a local man was arrested and charged with the murders of the two teens.

A community unable to recover

Living in Indianapolis, Indiana, close to the towns where both the Speedway and Delphi murders took place, Ms Cain and Mr Greenlee have seen firsthand the impact unsolved murders can have on a community.

“It’s harmful and traumatic for the community as it can spread paranoia,” says Ms Cain.

And it doesn’t matter if the case is five years old – like the Delphi murders – or 40 years old – like the Burger Chef murders – says Mr Greenlee.

“It’s really devastating to the families. If you lose someone you love, it doesn’t matter if it was yesterday or last week or 40 years ago if you don’t have answers – especially if it happens in a small town as it’s always in the back of people’s minds,” he says.

“You go to the store and see people and before you know it you wonder if someone in the store had something to do with it.”

Ms Cain adds: “People see their hometowns being thrust in a new light. The murder becomes what the town is known for.”

Indeed, before the murders of teenage best friends Libby and Abby, Delphi was barely on the map.

Now it’s a town whose name is forever synonymous with the horrific crime.

Fears are growing that Moscow will soon become the same.

It had long been known as a college town, with University of Idaho students making up around half of the 25,000 residents – not to mention the character – of the small, safe border town.

Residents of Moscow have told The Independent of their fears that, if the killer or killers of the four students isn’t caught soon, the toll on the community will only escalate.

While it is perfectly understandable that the public wants a quick resolution in shocking murder cases, Professor David Carter, a criminologist who has studied police clearance rates, says this often doesn’t match up with the reality of police work.

The more expansive the crime and crime scene, the longer it takes to investigate.

“I understand the community need and social media need,” he tells The Independent. “We want to know what happened. We want to know who the suspect is.”

Clearing homicides

However, he says a case like the Idaho murders has numerous elements that police need to work through slowly and deliberately to get things right: a large crime scene, extensive blood at the murder site, and multiple victims. Then, there’s all the usual elements of police work: interviewing witnesses, searching for surveillance footage, and cross-referencing information between different evidentiary sources.

“It’s incredibly time-consuming to do all this,” Professor Carter says.

The Moscow Police Department declined The Independent’s request for comment.

Idaho State Police say they are working “around the clock” in their mission to assist the Moscow police as the departments examine more than at least 113 pieces of physical evidence, as well as sifting through thousands of digital tips.

An Idaho State Police spokesperson told The Independent going through this mountain of information carefully and effectively will take time.

“We need the public to understand, unlike what is portrayed on television, complex investigations take time and resources,” the agency wrote in a statement. “Investigators comb through thousands of pieces of evidence, tips, leads, and digital media to understand the crime and capture the individual(s) responsible. Investigators keep an open mind, and no option is out of the question when they investigate leads.”

Despite the complicated nature of the case, there may be one detail about the Moscow Police Department that gives those searching for justice in the Idaho murders concern. Police there tend to do far worse than their counterparts across the state in solving crimes.

Up until the student killings, there hadn’t been a murder in Moscow since 2015, so it’s difficult to compare the department’s homicide record to other agencies around the state and country.

However, generally speaking, Moscow police only cleared about a quarter of “Group A” crimes between 2016 and 2021, according to The Independent’s analysis of state data, a broad category which includes everything from murder to theft. The state average during this same period was a clearance rate over 50 per cent.

More broadly, clearance rates in homicides have been declining, period, since the 1980s, when police solved closer to 70 per cent of murders, according to federal data.

Explanations for this decline range from crimes increasingly being committed between strangers rather than associates, to the rise in gun violence, to police being more accountable and less likely to stitch together flimsy charges than in the past.

“The reasons are multifaceted,” says Mr Hargrove, of the Murder Accountability Project.

“The number one reason is a lack of resources. Places where police simply don’t have enough people or enough investment or crime scene technicians are much less likely to clear murders.

“As a rule of thumb, a detective should be assigned no more than four or five homicides a year. Unfortunately, the reality is a lot of cities can’t follow those guidelines as they don’t have the people. It’s as simple as that.”

It’s unsurprising then that the data shows that murders that take place in rural communities where fewer crimes are generally committed are more likely to be solved than murders in urban areas.

As far as Ms Bobertz is concerned, one of the main reasons many murders including her cousin’s have gone unsolved is that “the laws work for the perpetrator not the victim”.

“There’s so many hoops you have to jump through and a lot of steps that I don’t think a lot of people are aware of,” she says.

That’s why she is calling for legislation to be passed which would allow law enforcement to collect the DNA of homicide suspects.

Whatever the reason for declining clearance rates, it’s not a universal phenomenon.

Some police outfits still solve nearly all their murder cases, so communities are right to expect a swift and professional response from police when a killing occurs, according to Charles Wellford, emeritus professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Maryland-College Park.

“That variation tells us something important,” he told The Marshall Project earlier this year. “It says that it’s not inevitable that there will be low clearance rates.”

This may offer hope to the grieving families and community of Moscow as the investigation enters its fifth week.

Hopes for Moscow

Just as doubts in the ability of law enforcement reached a boiling point, investigators revealed what appears to be the biggest break in the case so far.

An undentified car – a white 2011-2013 Hyundai Elantra – was spotted near the students’ home in the early hours of 13 November, around the time that the four victims were killed.

Investigators are looking to speak to the occupant or occupants of the vehicle and are urging the public to come forward with any information.

It might just be the missing “piece of the puzzle”, police said.

Whether it takes a week or a year, neither the Moscow police nor the families of Kaylee Goncalves, Madison Mogen, Xana Kernodle and Ethan Chapin are giving up.

“We’re gonna get our justice,” Goncalves’ father Steve Goncalves told an audience at a community vigil earlier this month.

“We’re gonna figure stuff out. This community deserves that.”