He grew up obsessed with ‘The Thomas Crown Affair’ – then committed a crime even more outlandish than the film

Truth about Ted Conrad, aka Thomas Randele, only emerged on his death bed, writes Andrew Buncombe

As a child in Cleveland, Ohio, Peter Elliott came to learn the name Ted “Theodore” Conrad at an early age.

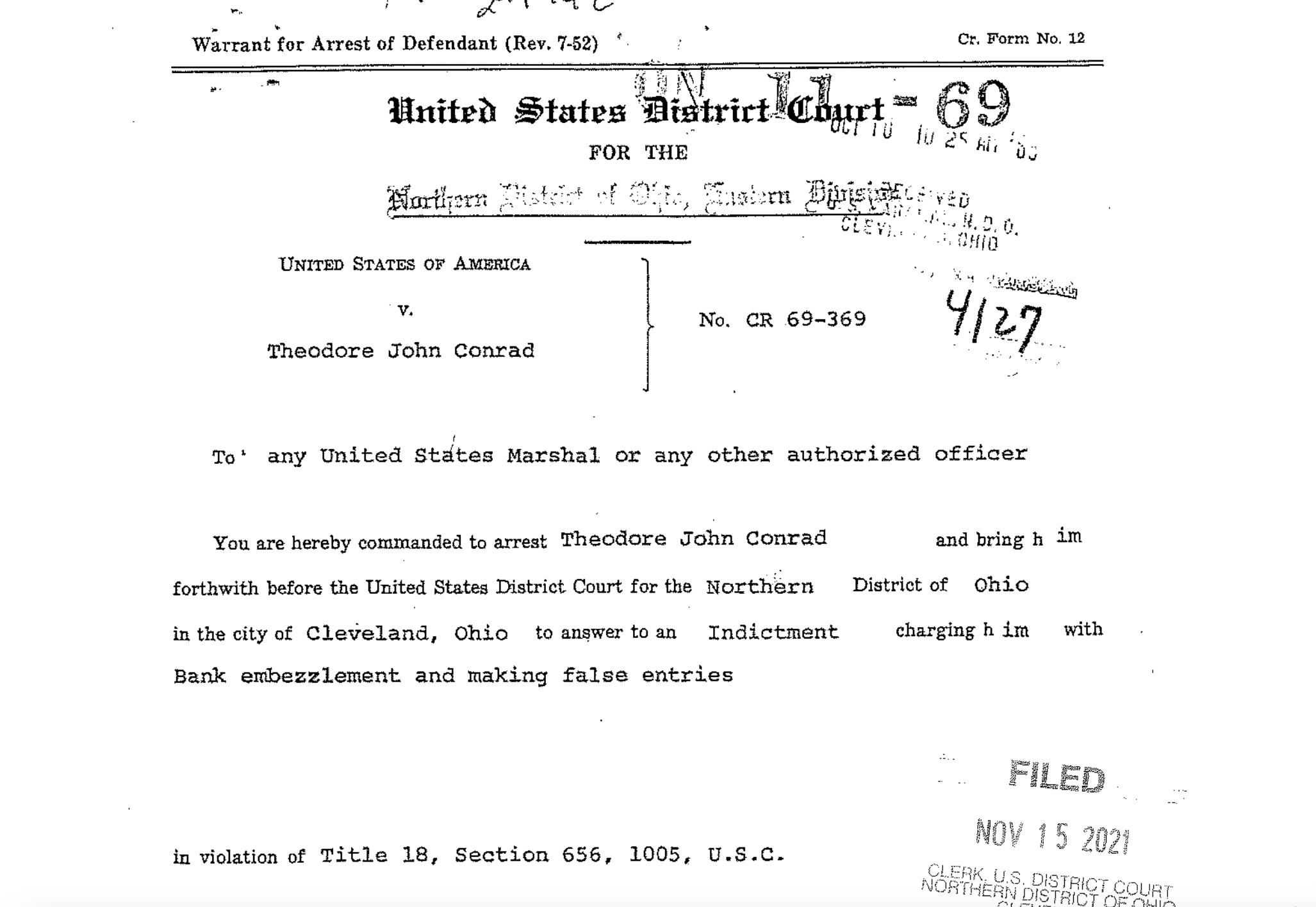

Elliott’s father, John Elliott, was a deputy US Marshal and took part in the effort to solve what became one of the city’s most notorious crimes, the theft in 1969 of $215,000 from the Society National Bank.

Conrad, obsessed with the 1968 movie The Thomas Crown Affair, starring Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, told friends he believed he too could steal money from a bank. Moreover, he would not require the complex heist featured in the movie directed by Norman Jewison; Conrad had a job in the Society National Bank that gave him access to the vault.

All he needed to do, was to engineer a situation whereby he was left alone there, a breach of the bank’s protocols, but something easy enough to secure by telling a colleague they could knock off early.

And that is precisely what the 20-year-old Conrad did. According to the authorities, on Friday July 11 1969, he walked out of work, with a paper bag containing the cash, today worth $1.7m.

And then he disappeared. His closest friends say they never heard from him again. The authorities have no evidence he even spoke to his parents, who were divorced, or any of his three siblings.

One friend imagined Conrad had made his way to the southern oceans, his hand on the tiller of an expensive yacht.

Yet, that is not what happened. Recently it was revealed that after leaving Cleveland, Conrad in 1970 had made his way to Boston – the city where much of The Thomas Crown Affair was filmed – obtained a new social security card with a fictitious name, Thomas Randele, added two years to his age, and started a new life.

He married, had a daughter, worked selling cars, and as a golf professional, and was known as a kind and cheerful man with a ready smile, someone always willing to help. Among his friends was a retired FBI agent.

Last May, stricken by cancer, he confessed the truth to his wife of 40 years, Kathy. Presumably reeling from he had told her, she nevertheless invited some of his golfing buddies and former colleagues to their house, to say one final farewell. By that point he was too ill to speak.

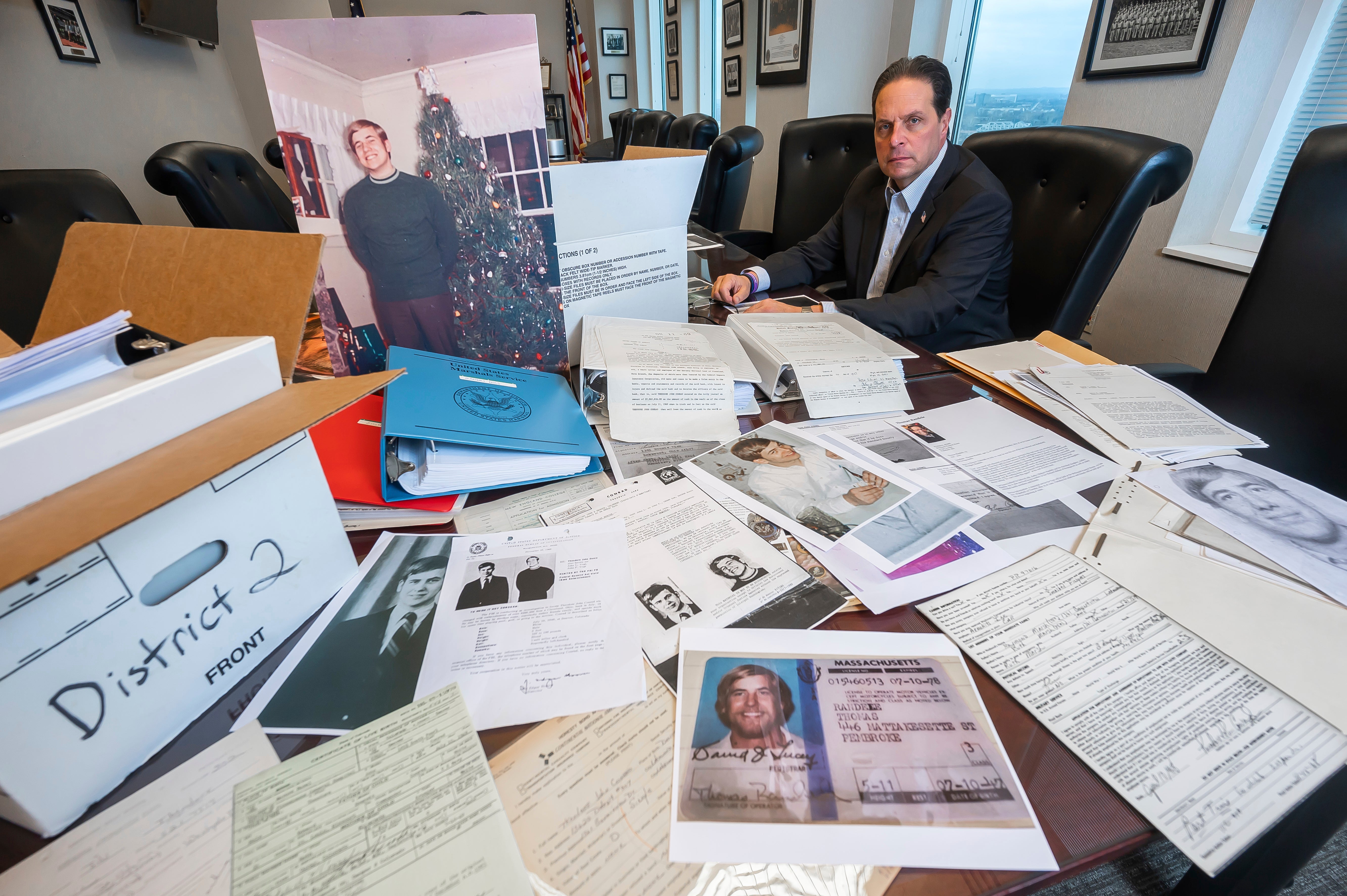

Six months later the authorities knocked on her door, asking for her help with that unsolved crime from a half-a-century ago. The officer who spoke to her was Peter Elliott, who had followed his father into the US Marshals Service and was now seeking to close the circle on the mystery.

“I knocked on the door, and his wife invited me and my deputy in,” Elliott tells The Independent. “She was a little reluctant at first to say anything, and I told her I was not there for her. I said, ‘You’re not in trouble. I’m just here because I don’t think your husband is who he said he was’.”

Elliott says the journey that took him from his offices in downtown Cleveland to a quiet street in the city of Lynnfield, part of the Boston metropolitan area, contained a number of twists.

For many years, Elliott’s father was quietly obsessed with the crime, and trying to solve it. The name Ted Conrad got thrown in and mixed up with every day conversations.

“We’d be at dinner and he would say ‘Pass the mashed potatoes – and where do you think Ted Conrad is’,” says Elliott, 59.

Part of his father’s fixation, says Elliott, was that Conrad had moved to the Cleveland neighbourhood of Lakewood as a teenager and attended Lakewood High School. Elliott and his father also lived in Lakewood. Both Conrad, and Elliott’s father went to the same doctor. For some time, Conrad worked in a store where Elliott took his son to buy ice cream.

“It’s kind of bizarre, right,” says Elliott. “But my father really took an interest. For my father, when I was growing up, that was literally his fixation.”

Even after his father retired in 1990, he retained an interest in the case, as his son continued to get tips and suggestions about what may have happened from across the world. Five years ago, he received a tip from the authorities in Britain, suggesting Conrad may have stayed at boarding house in the city of Canterbury. Elliott and his team looked into the tip, but found it was not their man.

What was his father’s theory?

“Well, he had a bunch of different theories going over the years,” says Elliott. “Sometimes he thought Conrad was alive. Other tips came in saying this and that. He thought Conrad did the same thing again, and he followed up some of those leads. You know, we’ve followed up leads from Hawaii to Oregon to England.”

In its own way, the reality was even more surprising. And much closer to come.

For the bulk of the time after he left Cleveland, Conrad, the one time wannabe-master thief, was living just 650 miles to the east, in a suburban neighbourhood, where he started a new life, and apparently slipped right in.

He played so much golf he became good enough to be a club professional at the Pembroke Country Club, south of Boston, where he gave lessons and eventually become the manager.

In 1982 he married his wife, Kathy Mahan, whom had met in the early 1970s, and they had a daughter, Ashley. He later worked selling cars at several dealerships, a career that would spread over four decades. His friends said he kept a set of golf clubs in the showroom and when business was slow, he would practice swinging a 7-iron.

“He was just a gentle soul, you know, very polite, very well spoken,” Jerry Healy, who first met him a dealership in Woburn, Massachusetts, recently told the Associated Press.

He added: “It never dawned on us, and that’s a half a dozen guys that aren’t easy to fool.”

Matt Kaplan, another of the half-dozen or so friends who played together and socialised, said the man they knew as Thomas Randele was the definition of a “gentleman”.

“The only way it makes sense is that at that age he was just a kid, and it was a challenge kind of thing,” Kaplan said of the 1969 bank theft.

“It’s not like he became a professional bank robber.”

He added: “If he would have told us way back when, I don’t think we would have believed him because he wasn’t that kind of guy. The man was different than the kid.”

His wife did not respond to enquiries from The Independent. Indeed, her only comment to the press since the truth about the man she lived with for more than 40 years became public, was to the Cleveland Plain Dealer. She said: “I’m still grieving the loss of my husband, who was a great man”.

Elliott says the authorities were only able to solve the mystery of the missing bank thief after he had died. Somebody – he will not say who – tipped them off about an obituary for Thomas Randele his family arranged to have published in the weekly Lynnwood News. It is not clear how the tipster understood that this obituary, amid the countless thousands published every week across the nation, led to Ted Conrad.

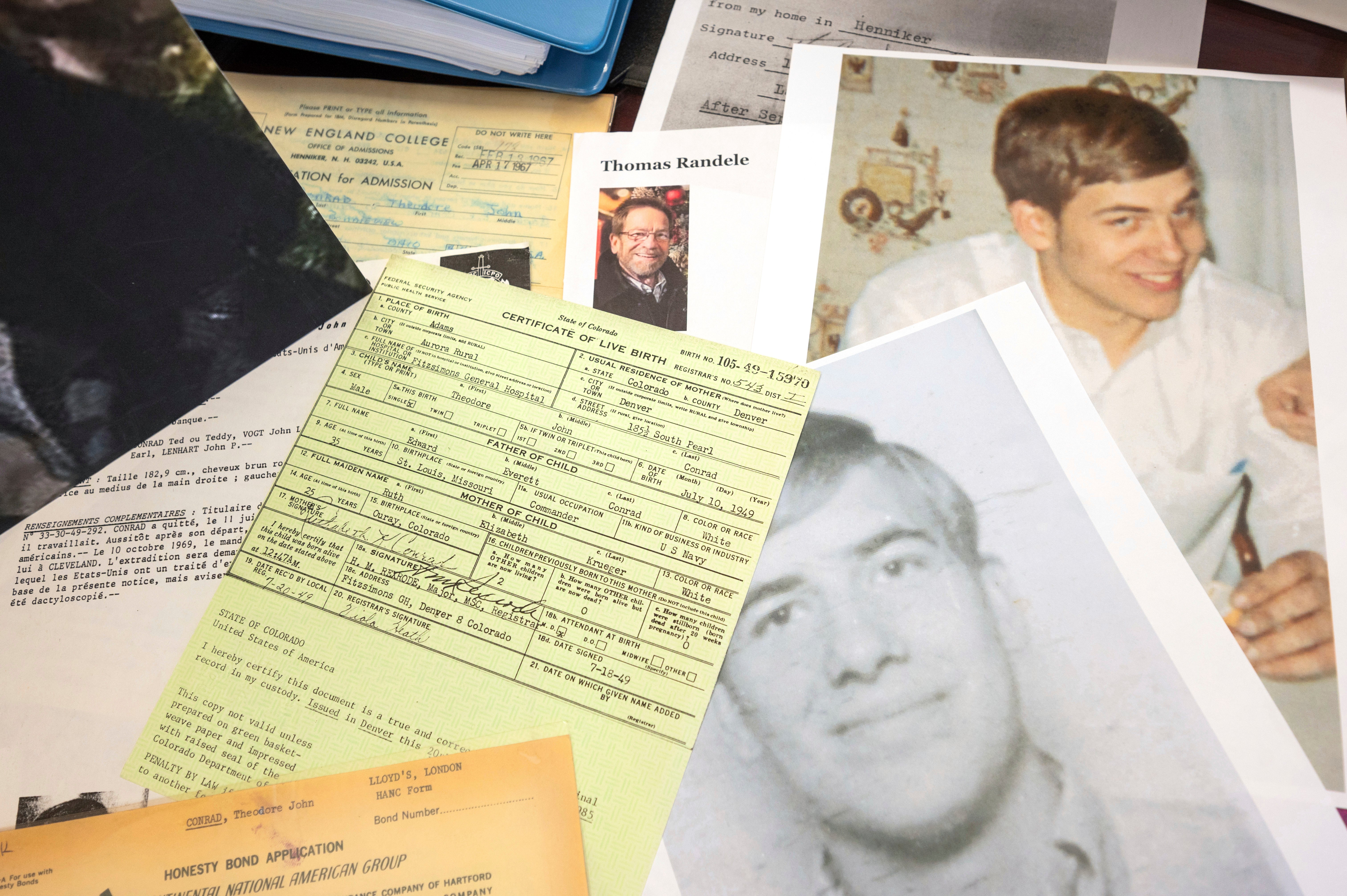

It noted that he had been born in Denver on July 10, that his parents names were Edward and Ruthabeth, and that he had attended New England College in New Hampshire.

All of these – apart from the year of his birth, which he had changed in 1970 – matched with what the authorities knew about Ted Conrad.

Elliott says they began to investigate the matter, and discovered that Thomas Randele had filed for bankruptcy in 2014, and his team was able to obtain from the Boston courts, the filing that contained his signature. He says among the documents his father had collected over the year was Conrad’s 1967 application to New England College, located in the town of Henniker, which had been signed by the young man. They looked the same.

“One thing about handwriting, good or bad, is that it doesn’t really change over a period of time. You may get a little sloppier, but you still do your Ds same way and so on,” he says.

“If you take a look at these signatures, you know right away.” He added: “I really need to give my dad credit for this. Because, although he had passed away, we were able to use those documents he had collected over the years.”

Armed with that information, Elliott and his deputy were able to travel to Lynnfield, and approach the property, set among mature trees, where Conrad is believed to have lived since 1986.

He says he believes Conrad’s widow had been expecting that sooner or later there would be a knock on the door from someone like him. “I think she anticipated one day, somebody was going to find out something, is what I guess,” he says.

“She then admitted that, he had admitted he was really Theodore Conrad, before he passed away, and that he had taken the money back in the 60s, and regretted it, which I really do believe.”

Elliott says one of several sad elements about the tale is that the family is apparently short of money. He says there were more unopened bills stacked in the house than he had ever seem, an irony for a man who once stole from a bank.

Another challenge for the family, he says, as it grieves the loss of a father and husband, is that Conrad’s next of kin are living with a false name.

Does Elliott believe there was a sense of relief from Conrad’s widow and daughter?

“Yeah, I do think there was part of them that knew this was going to come up. It’s an embarrassment in a lot of ways to them,” he says.

“And, because everything I know about – let’s call him Thomas Randele – is that in that life he was a good person, a good man, a good father, a good husband, a good family man, a good friend to many, and from what I heard, a pretty good guy.”

He adds: “So for them, I think there was part of it, where they didn’t want this to come out. But I think they knew eventually it probably would.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.