Could the verdict in the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers spell the end for so-called ‘vigilante justice’?

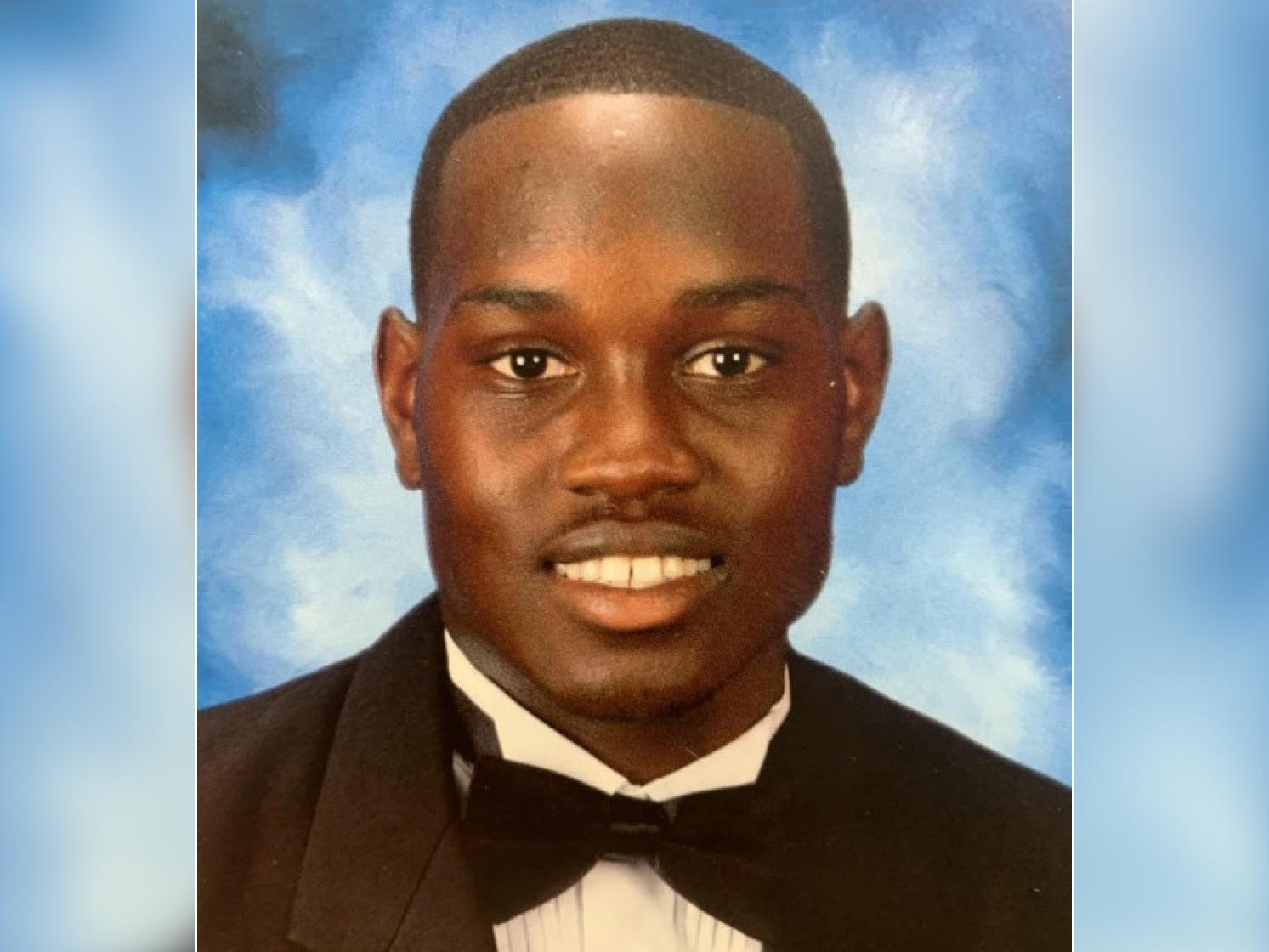

The Black jogger’s death and the trial of the three white men accused of his murder has exposed the blurred lines between vigilante killings and America’s laws on citizen’s arrests and self defence, Rachel Sharp writes

It’s a tale as old as time.

Everyday citizens decide to take the law into their own hands in what they claim is the pursuit of justice.

In this case, a Black 25-year-old former high school football star ended up dead, shot twice at close range on a spring afternoon in Georgia, while his family said he was out for a run.

Ahmaud Arbery’s death - and the trial of the three white men accused of his murder currently underway in Brunswick - has shone a spotlight on the concepts of self defence, citizen’s arrest, stand your ground and open carry laws.

For years, these laws - many of them rooted in statutes drawn up before America was even founded - have offered protection to the people pulling the trigger.

But the high-profile nature of the trial and its prominence in the racial justice movement has raised questions about where the line is drawn between vigilante justice and, quite simply, racism and murder.

“People talk about vigilante justice but what it turns into is vigilante injustice,” Ira Robbins, a law professor at American University’s Washington College of Law, tells The Independent.

The three white men charged with Mr Arbery’s murder claim they were carrying out a citizen’s arrest because they suspected him of break-ins in the area after he was spotted on surveillance footage entering a home under construction in the months prior to his death.

The man who then pulled the trigger - Travis McMichael - claims that he then acted in self-defence as Mr Arbery grabbed his shotgun when he had it pointed at the unarmed Black man. He gave a tearful account at his trial of what he described as a “life or death situation”.

Prosecutors claim Mr Arbery was “under attack” from the three men who had no reason to think that he had ever committed a crime. The Black man’s family has called his death a “modern-day lynching”.

On Thursday, the defence rested its case ahead of closing arguments beginning on Monday.

All eyes will then turn to the jury of 11 white people and one Black person to reach a verdict which experts say could have a far broader impact than simply determining the fate of the three defendants.

Regina Bateson, assistant professor at the Graduate School of Public and International affairs at the University of Ottawa who has written on the topic of vigilantism, believes the verdict could see a shift in public opinion around the entire concept of vigilante justice.

“This case has the potential to be transformative,” she tells The Independent.

Vigilantism and power hierarchies

Ms Bateson says vigilantism is rooted in “hierarchies of power” and people asserting their power over other people in less powerful positions in society.

This means vigilantes are also in a position of power to shape the public discourse after their actions.

“Vigilantes often try to seize the power of controlling public debate and shaping public opinion,” says Ms Bateson.

“So what we have seen in other cases like this is that people first take the law into their own hands, then they use their power to try to win public support on the ground and then the state responds by expanding the envelope of permissible behaviour.”

Ms Bateson explains that, early on in the case, the three suspects were out on top in this power dynamic.

It was 74 days before Travis and his father Gregory McMichael were arrested for the murder of Mr Arbery.

It was then another 14 days until their neighbour and co-defendant William “Roddie” Bryan Jr was arrested.

Gregory McMichael was a retired police officer with Glynn County Police and had worked for two decades as an investigator in the Brunswick district attorney’s office.

Hours after the killing, he called his former colleague - then-DA Jackie Johnson - to ask for “advice”.

Ms Johnson went on to recuse herself from the case before handing over to another DA who recommended no charges be brought, before also recusing himself.

What went on behind the scenes is now part of a separate criminal case with Ms Johnson facing criminal charges over her handling of the investigation into Mr Arbery’s death.

For three months, the three white men managed to evade any repercussions until footage of the shooting was released online.

However, since then, says Ms Bateson, the case has “bucked the trend” around power and vigilantism.

“What’s striking in this case and where it could go is that this has already flipped the pattern,” she says.

“Instead of doubling down and condoning their actions, the state is now pushing back and defining the bounds of acceptable behaviour.”

The three men were all eventually charged and are standing trial for Mr Arbery’s murder.

During the trial, several members of law enforcement have taken the stand and denounced the defendants’ actions, “showing that the vigilantes are not the allies of law enforcement that they believe they are”.

And the Republican-led state of Georgia has repealed the citizen’s arrest law being used as the defence.

Pro-vigilante laws

The Civil-war era citizen’s arrest law allowed any Georgia citizen to arrest another citizen if they believed they had committed a felony crime either “in his presence or within his immediate knowledge”.

Travis McMichael testified that he had a “reasonable” belief that Mr Arbery could have broken into the home under construction belonging to Larry English when his father said he saw him running past the house.

He claimed this belief that Mr Arbery may be responsible for burglaries led him to jump in his pickup and chase Mr Arbery on the day he shot him dead.

Witnesses for the prosecution testified that he had not even seen Mr Arbery at the property that day and had no knowledge that he had even been at the site or committed any crime.

Police bodycam footage from an incident two weeks before the shooting showed a police officer telling the McMichaels that Larry English did not believe Mr Arbery had stolen anything from the property.

The suspects were told that Mr Arbery could be given a warning for trespassing - a misdemeanor under Georgia law, not a felony.

Following Mr Arbery’s death, Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law was repealed and replaced with a bill only allowing certain citizens to carry out an arrest under limited circumstances, such as a store owner who catches someone shoplifting.

But, while the repeal of the law was hailed, most other US states still have some version of citizen’s arrest law in place.

And other laws that critics say encourage vigilantism are still in place in Georgia.

Under self defence laws, a citizen can justify hurting or killing another citizen if they have a reasonable belief that they themselves are in danger.

If the person is the “initial aggressor” of the situation then they do not have the right to self defence.

Travis McMichael told the court that Mr Arbery grabbed his gun and was “attacking me” leaving him in fear for his life when he shot him.

"I shot. He had my gun. He struck me. It was obvious that he was attacking me, if he would have gotten the shotgun from me, it was a life or death situation,” he said.

Under cross-examination, Travis McMichael admitted that he told police officers in an interview hours after the killing that “I can’t remember” if Mr Arbery had grabbed his gun.

Who the “initial aggressor” was in the situation is also blurry under the law because of the McMichaels’ claims they were carrying out a citizen’s arrest and that Mr Arbery didn’t comply as the armed white men chased him through the neighbourhood.

Meanwhile, stand your ground laws (which many states including Georgia still have) make it legally permissible for a citizen to use deadly force to defend themselves, other people or property if they believe it is necessary to prevent death, bodily injury, or a felony.

Under this law, there is no obligation to retreat from the danger even if it is safe to do so.

Many southern states like Georgia also have open carry laws meaning it is legal to carry a firearm openly if the person has a permit.

Reckless vigilantism vs lawful self defence

So what then is the difference between reckless vigilantism and lawful self defence?

It’s this question that the trial ultimately centres around.

But, because the laws all differ state-by-state, boundaries between the two more generally can be murky.

And the laws are especially open to interpretation, explains Mr Robbins, who has written a paper on vigilantism and citizen’s arrest laws.

“To have the reasonable belief that you have a right to use deadly force and to stand your ground is subjective,” he says.

It does not matter if your belief - that you are in danger so must act in self defence or that a person has committed a crime so you have a right to arrest them - is proven incorrect.

It only matters that it is “reasonable” that you had the belief.

“And it’s also subjective to say what a reasonable person would do,” says Mr Robbins.

Mr Robbins says the entire case for the three men on trial is a house of cards resting on the now-repealed citizen’s arrest law.

“Number one, was there a right to effect a citizen’s arrest in that circumstance? If not, then you don’t get to self defence,” he says.

Vigilantism is equally complex to unpack.

Ms Bateson explains that the types of vigilantism run along a spectrum from: collective to individual, public to private, violent to non-violent, offensive to defensive, and spontaneous to institutionalised.

More often than not, vigilantes will portray themselves as defenders of something.

In the case of the McMichaels, they claim they were defending their community from a suspected burglar.

However, Ms Bateson says their action of “going out looking for people to catch” when they jumped in their pickup truck and chased Mr Arbery through the neighbourhood leans into the offensive end of the spectrum.

For Mr Robbins, the difference between vigilantism and citizen’s arrest comes down to training.

“Vigilantism is untrained people taking the law into their own hands,” he says.

“Because I don’t think most ordinary citizens know what a citizen’s arrest is and, under what circumstances, they do or don’t have the right to do things.”

When Travis McMichael took the witness stand at his trial, he testified that he had gone through law enforcement training when he served in the US Coast Guard from 2007 to 2016.

He described being trained in de-escalation and control, use of force, and how to show your weapon to encourage compliance.

He did not mention being trained around Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law and he was not a trained law enforcement officer when he killed Mr Arbery.

Under cross examination, he was asked about his thoughts on vigilantism.

Prosecutor Linda Dunikoski showed him Facebook posts where he had said anyone committing crimes in his neighbourhood was "playing with fire" and urged people to "arm up” in response to a spate of crimes.

In a conversation with another social media user who said their father was “old as dirt and doesn’t care about going to jail”, Travis McMichael agreed that his father was “the same way”.

He added: “Hell, I’m beginning to feel the same."

Parallels with Kyle Rittenhouse

It’s impossible not to draw parallels between the trial of the McMichaels and Mr Bryan and the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse, who was acquitted by a jury on all five counts, including homicide, at a courthouse in Kenosha, Wisconsin, last week.

In both cases, white men armed themselves with firearms and shot other men dead before claiming they were acting in self defence.

Mr Rittenhouse was 17 when, armed with an AR-15, he travelled to Kenosha during protests over the police shooting of Jacob Blake last summer.

He shot and killed two men and wounded a third.

Like the men accused of Mr Arbery’s murder, Mr Rittenhouse claimed self defence after claiming he was attacked by the people he shot and had no choice but to use deadly force to protect himself.

He also claimed his reason for being there that night was to protect his community (the Illinois teenager said his father lived in Kenosha and he felt part of the community).

The big difference between the two cases, says Mr Robbins, is the race of the victim and the indication that the suspects racially profiled Mr Arbery by assuming he was committing a crime.

According to Mr Robbins, citizen’s arrest laws date back to medieval England and the year 1285 when, before organised police forces were created, citizens were made responsible for enforcing the law and capturing fellow citizens who broke it under the order of the king.

In Georgia, the now-repealed law is closely rooted in America’s slave trade past.

The law was passed in 1863 - the same year as the Emancipation Proclamation when slavery ended in America and the Fugitive Slave Act (calling on “good citizens” to to return runaway slaves to their owners) was repealed.

It’s then no surprise that the law has long been seen as a new way to deputise white people to detain Black people.

“In the US, vigilantism and race are inextricably linked,” says Ms Bateson.

“One of the terms we often use when discussing vigilantism is lynching which emanates from racial terror in the US.”

Ms Bateson argues that had the roles been reversed - and a group of three Black men chased down a white man and shot him - they would not have been looked on as “upstanding members of the community”.

“They might not have even survived the aftermath,” she says.

“The [defendants’] whole argument and framing of what happened has been open to them because of their race.”

White vigilantism

White vigilantism is not a new concept, however.

The death of Mr Arbery has stark similarities to the case that led to the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement and first threw stand your ground laws into the national spotlight.

It was 2012 when former neighbourhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman shot dead unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida.

Mr Zimmerman was acquitted of all charges after claiming he acted in self defence and under the stand your ground law.

Then, in 2019, white woman Hannah Payne shot and killed 62-year-old Black man Kenneth Herring in an alleged road rage incident in Georgia.

Mr Herring had left the scene of a crash after their vehicles collided. Ms Payne is accused of chasing after him and then shooting him dead.

Ms Payne, who is awaiting trial, is also claiming she was trying to carry out a citizen’s arrest under Georgia’s law at the time.

Joseph Marguiles, professor of practice, law and government at Cornell Law School, tells The Independent that the deaths of Mr Martin and Mr Arbery especially are very similar as they involve the “convergence of citizen’s arrest, open carry gun laws and stand your ground”.

“The Trayvon Martins of the world and the Ahmaud Arberys of the world are predictable when you combine the three laws with what we know about implicit and explicit bias and the associations white people make between blackness and criminality,” he says.

“I don’t think the laws are drafted to protect Black men. The reasonable judgements are not to protect Ahmaud Arberys.”

Instead, he argues, the laws protect the people who commit a crime while acting on the suspicion - true or false - that another person has or is about to commit a crime.

Research from gun control nonprofit Everytown for Gun Safety found that homicides where white shooters killed Black victims were five times more likely to be deemed justifiable than the other way around in stand your ground states.

Overall, the rate of firearm-related homicides is also higher in stand your ground states, with 5.4 killings per 100,000 people compared to 3.6 per 100,000 people in states without such a law.

The verdict

Other states will be watching what happens in Georgia closely as a test case about their own citizen’s arrest and self defence laws.

In recent months, lawmakers in New York, Florida and South Carolina have all proposed bills to repeal the laws in their states but progress has been slow.

And if a not guilty verdict is returned, Mr Marguiles fears that deaths like Mr Arbery’s will continue to occur.

“If [the defendants] are acquitted it will reaffirm the perceived legitimacy of the kind of biases that led them to chase down Mr Arbery in the first place and these laws will continue to do their damage,” he says.

However, if the McMichaels and Mr Bryan are convicted of murder, it could mark a major step forward in bringing about an end to ordinary citizens arming themselves with firearms, going out into the streets and taking the law into their own hands, says Ms Bateson.

“The US is a country awash in weapons and a long history of racial terror and immunity for these killings and that doesn’t go away overnight,” she says.

“But the reassessment of stand your ground laws in recent years, a critical reassessment of self defence and a repeal of citizen’s arrest laws has the potential to deter this kind of behaviour and to hold people accountable when it does occur.

“And now the verdict also has the potential to show other vigilantes that there are consequences to their actions.”

As Mr Robbins says: “The bottom line is, people shouldn’t be taking the law into their own hands.”