‘My world is shattering’: The foreign students left stranded by coronavirus

As their bank accounts dwindle, some international students say they have had to turn to food banks for help

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

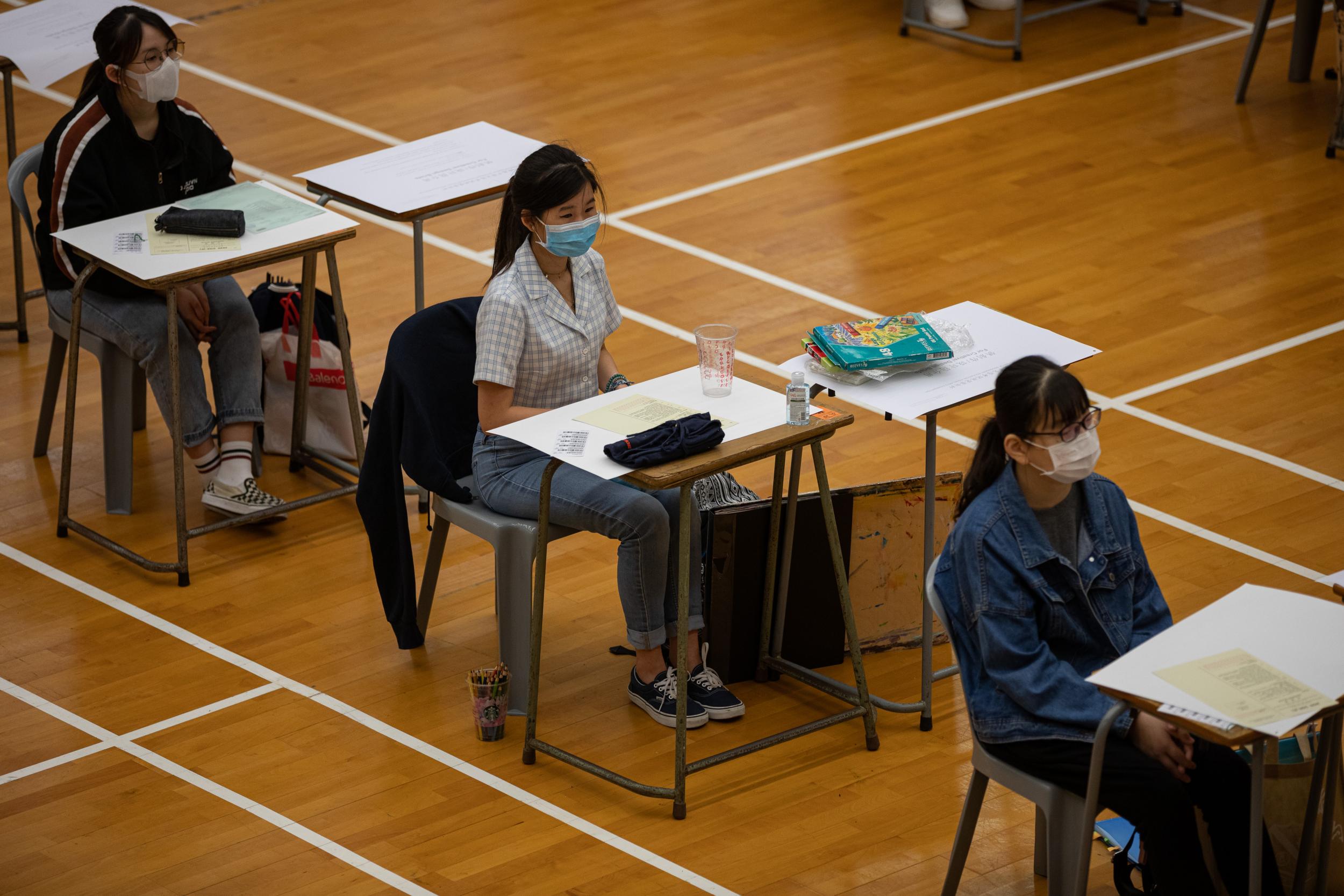

Your support makes all the difference.When universities abruptly shut down last month because of the coronavirus pandemic, many students returned to their parents’ homes, distraught over having to give up their social lives and vital on-campus networking opportunities. Graduating seniors lost the chance to cross anything but a virtual commencement stage.

But the campus closures have created much greater calamity in the lives of the more than a million international students who left their home countries to study in the United States. Many had been living in college dorms and were left to try to find new housing, far from home in a country under lockdown.

A substantial number of international students are also watching their financial lives fall apart: visa restrictions prevent them from working off campuses, which are now closed. And while some come from families wealthy enough to pay for their housing or whisk them home, many others had already been struggling to cobble together tuition fees that tend to be much higher than those paid by Americans.

As their bank accounts dwindle, some international students say they have had to turn to food banks for help. Others are couch surfing in the family homes of their friends but don’t know how long they will be welcome. Those who rushed to fly home before international borders closed are not sure they will be able to come back.

“My world is shattering,” said Elina Mariutsa, a Russian student studying international affairs and political science at Northeastern University whose parents sold an apartment and borrowed money from friends to pay for her previous semesters of college.

She is all but certain that, with the Russian ruble’s recent rapid devaluation amid the ongoing global economic collapse, her family will be unable to pay the $27,000 bill for her final semester of college — let alone help her with living expenses now.

“I’m not sure if I’m going to be able to graduate. Right now we definitely can’t pay for the last semester, and it’s literally just four courses left,” she said.

Universities, which often receive a substantial share of their budgets from foreign students, said they moved quickly to help international students by opening a limited number of dorms when possible, flying students home in some cases and lobbying the federal government for support. New York University, which has more foreign students than any college in the country, created emergency grants available to international students.

“It’s hard and it’s constantly evolving,” said Jigisha B Patel, the chief adviser for international students at Northeastern. “Everybody has really moved towards doing everything they can during this time.”

The federal government has stepped in to help college students who have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic, but in keeping with its America-first agenda, the Trump administration announced on Wednesday that international and undocumented students would be excluded from the roughly $6bn in federal aid targeted to help students pay for expenses like food and housing.

Many students said the help that was provided by their universities was not nearly enough.

“It was a very hectic moment because I had no idea where to go,” said Anna Scarlato, an Italian student who learned in March that she would be kicked out of her dorm at the University of Chicago within days.

With nowhere else to go, Scarlato moved to her boyfriend’s dorm at a different school, but the next day they learned that campus housing was closing there, too.

Scarlato agreed to sublet a room in a Chicago apartment but then learned that her parents, who were under lockdown as a result of the pandemic in Italy, would be unable to get to a bank to transfer her any money for rent.

At the last minute, her boyfriend’s mother bought Scarlato a ticket to go home with him to Orange County, California. “I have no idea where I’m going to be in the next two weeks or a month or two months,” she said. “It feels like I’m being a parasite in some way.”

When classes were cancelled at Yale University, Sam Brakarsh, a student from Zimbabwe, feared carrying the virus back to his ageing parents or getting stranded by flight restrictions. The Internet in his parents’ home works for only three hours a day.

Instead, he decided to bunk temporarily with a classmate from Amherst, Massachusetts, who was moving home with his parents and younger brother.

Now, hoping to avoid overstaying his welcome and the fact that his student health insurance only works near campus, Brakarsh is planning to move next into an extra bedroom in the home of a professor.

But “nothing is definitive”, he said.

Some students have been reluctant to share the extent of their troubles with their families, who were already struggling to pay for their schooling.

Stephany da Silva Triska said her mother in Brazil stopped eating out in restaurants, didn’t replace her old car, and cut back on vacations so her daughter could study politics at California State University, Long Beach.

In turn, Triska worked hard to justify her mother’s sacrifice. She was chosen by professors as an outstanding senior in her major and won a prestigious international policy fellowship.

A ceremony to recognise her achievements has been cancelled and her fellowship is on hold. But she has bigger problems, including whether she will be able to finish college at all. Her mother’s interior design business, which funded the portion of her education that was not covered by scholarships, has dried up.

Triska, who lives in an apartment she pays for with her student job, still owes $600 towards the tuition fee for her final semester of college.

“Every time I log into my student account, I see the $600 balance. I don’t even know who I should go to if they would be open to negotiating the remaining balance,” Triksa said.

Students who rushed to airports to beat looming border closures and wait out the pandemic at home also fear they will face legal hurdles when they try to return to the United States to complete their schooling.

Mercy Idindili, a sophomore at Yale studying statistics, said she returned to Tanzania after feeling pressured to do so in a series of emails from college administrators that made clear the institution was going to make “very few exceptions” for international students who wanted to stay in the United States.

At first, Idindili made plans to stay with a friend in Georgia, but when other international students warned her that the arrangement could become uncomfortable if it went on for too long, Idindili decided to go home at the last minute.

Before leaving on a ticket paid for by the school, she made sure to warn her professors that she was going to be seven hours ahead and that her Internet access would be inconsistent because of frequent blackouts.

“Honestly, that whole week was very hard,” she said, “I did cry a lot because I was so confused and so disappointed by everything.”

At first, she had been waking up at 3am to attend virtual lectures in a linear algebra class that was giving her trouble. Her professor has since begun recording the lectures for her, which is helping her keep up.

But Idindili’s visa to re-enter the United States expires in July, and American consulates abroad are all closed indefinitely. The State Department has also suspended visa processing until further notice.

“I’m just really scared of what happens if Tanzania doesn’t solve this problem soon enough, and the US consulate chooses to remain closed for a long time and I’m not able to renew my visa and go back to school,” she said.

The legal status of all international students has become less certain because of the coronavirus pandemic. Normally, their visas require them to take classes in person, rather than online. The Department of Homeland Security temporarily relaxed that rule in light of the crisis, but the exception could be reversed at any time.

Some students said they cannot wait for a more permanent solution to their visa problems. Emma Tran, who studies studio art and psychology at California State University, Long Beach, burst into tears explaining she only has enough money in her bank account to cover another month and a half of living expenses, and will likely have to return home to Vietnam.

Tran lost both of her campus jobs because of the coronavirus pandemic. Her parents’ income from an apartment they own, half of which they typically rent out to tourists, has also dropped precipitously.

Trying to stretch funds, Tran at first went to a food pantry on campus, but her parents discouraged her from taking donated goods that others might need more than she did. Since then, she’s resorted to eating rice for more of her meals and either skipping or limiting the amount of meat she consumes to save money.

“My mom said if this thing doesn’t get controlled in two or three months, I will have to go back home,” she said, “It’s really sad.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments