Florida teachers union sues over forced return to schools as coronavirus cases increase

Trump is threatening to defund schools that refuse to reopen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Florida’s largest teachers union sued top state officials on Monday over an order mandating a return of in-person schooling, drawing the courts into an increasingly politicised nationwide debate over when and how children can return to class amid the coronavirus pandemic.

The suit from the Florida Education Association asked a judge to stop Republican governor Ron DeSantis and education commissioner Richard Corcoran from requiring the return of in-person schooling without first reducing class sizes and ensuring that educators have adequate protective supplies.

The move came as confirmed cases of the coronavirus are increasing in many states, including Florida, raising fears in some quarters that a return to brick-and-mortar schools in the fall could put students and teachers at risk and exacerbate the spread of the virus. Others argue that reopening schools is a critical step in a return to normalcy.

Florida teachers are asking the court to strike down an emergency order by Mr Corcoran, saying it violates a requirement in the state constitution for safe and secure schools.

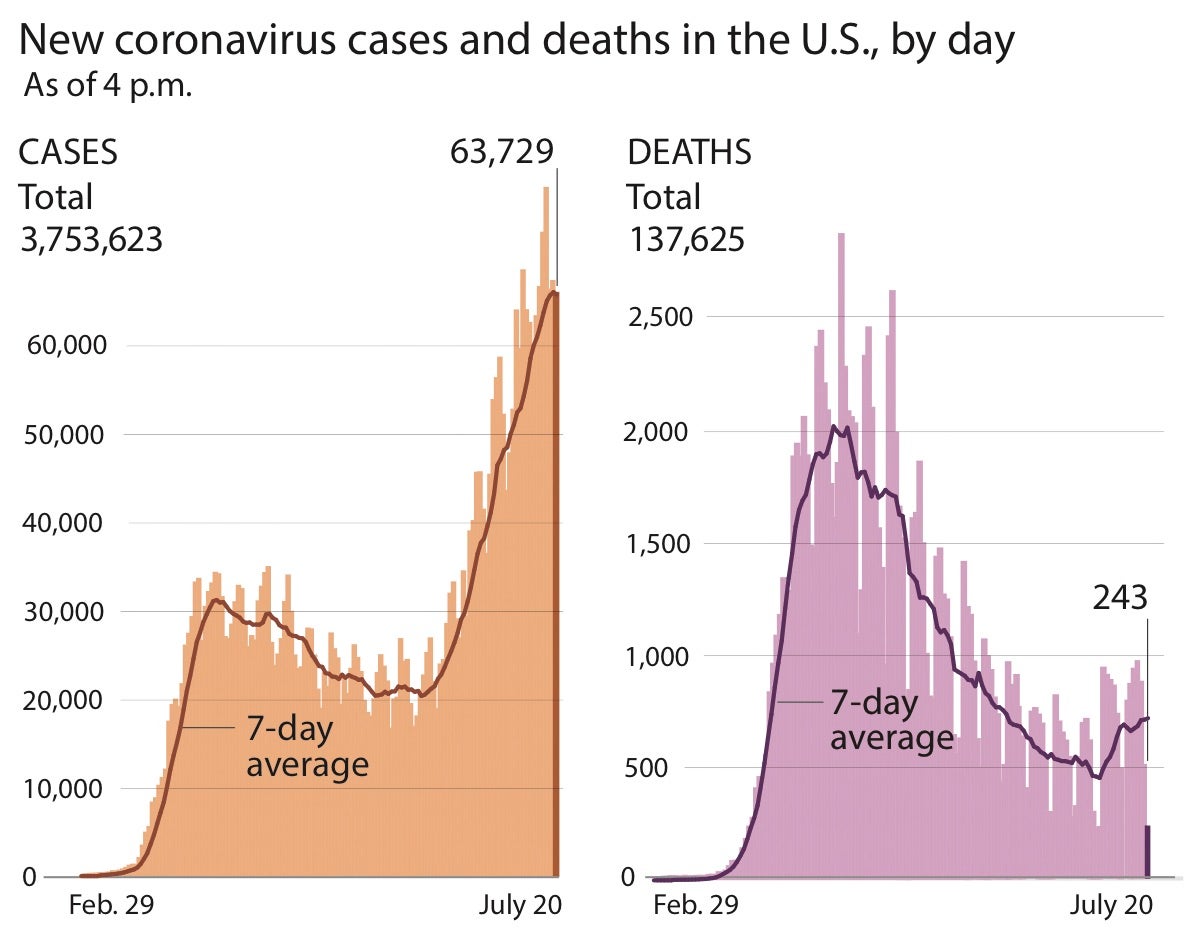

On Monday, the United States added more than 55,000 new cases and more than 380 new deaths – both below seven-day averages, though Monday typically sees lower figures than other days. Seven states and Puerto Rico reported new highs for currently hospitalised Covid-19 patients, with Florida reporting close to 9,500 inpatients.

At the same time, hospitalisations appear to be levelling off in Texas and Arizona. The two states combined still account for more than 18,000 of the estimated 56,000 currently hospitalised Covid-19 patients.

Officials say some of the recent increase in cases is probably attributable to increased testing, which was not widely available in the early days of the pandemic. But much also is probably caused by the rollback of government-imposed restrictions on business and social life, leading more people to have contact with one another and spread the virus.

The spikes have put pressure on state and federal leaders to take steps such as mandating the wearing of masks or slowing plans to reopen their economies.

Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot announced on Monday that she was tightening restrictions on bars, gyms and personal service businesses. Donald Trump said he would resume leading regular late-afternoon public briefings by the White House coronavirus task force and he more vigorously endorsed mask-wearing than he has previously, tweeting a photo of himself in a mask and suggesting that doing so was patriotic.

The Senate, meanwhile, returned to work for a three-week session before its August break. Lawmakers are under pressure to pass new coronavirus relief legislation before the November elections.

What to do about schooling has long been one of the thorniest dilemmas posed by the coronavirus – in part because the science about how the disease spreads among children, and from children to adults, is not yet developed enough to draw firm conclusions. After Mr Trump tweeted two weeks ago that schools “must” open in the fall, the issue has often been consumed by partisan bickering.

“We have managed to take what I think is one of the most important nonpartisan issues in America, which is getting our kids taught this fall, and turned it into a partisan battle,” said Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. “Here’s a crazy idea: let’s just do what’s good for kids and parents.”

Public health experts agree that children are generally less likely to get infected than adults, and they tend to develop milder symptoms. But children are not immune and a small number have died.

“They get the disease, and they do transmit,” said Michael T Osterholm, director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “The question is how much, and does that enhance transmission in the community?”

The data on that is mixed.

One study, from Australia, found that nine students and nine adults who contracted the coronavirus had close contact with more than 730 other students and 128 staff, but they could only be possibly linked to two infections.

Another large study from South Korea found that children under 10 years old appeared to transmit to others in their household far less often than adults did, though those between 10 and 19 years old appeared to transmit as much or more than adults.

“I’m going to await further data before I can stand in judgment whether we can assume that children are considerably less infectious than adults,” said Sten Vermund, dean of the Yale School of Public Health.

William Raszka Jr, a paediatric infectious-disease specialist at the University of Vermont Medical Centre, said some countries have reopened their schools without new outbreaks, while others have had problems. Of great importance, he said, is the level of spread in the community outside the school.

Places such as Vermont, which have relatively few cases, might be able to open up more easily than places such as Arizona or Florida, which are seeing cases spike, Mr Raszka said. He said high school and colleges might also have more trouble than elementary schools, as older children seem to be more acutely affected.

“Is that risk zero? No. We can’t develop a strategy that has zero risk,” Mr Raszka said. “But we can develop strategies that minimise that risk.”

Politicians and school leaders have taken varying tacks on how to address the crisis – with some advocating for partial or complete distance learning while others seek a return to in-person instruction. California Democratic governor Gavin Newsom, for example, issued rules last week that mean most schools will not reopen physical classrooms, while Texas reversed a previous order and allowed schools to delay in-person instruction. Texas’ attorney general has told religious schools that any local efforts to restrict their reopening might violate the constitution.

In an interview on Fox News Sunday, Mr Trump made clear that he favours face-to-face instruction and threatened to withhold federal funding from districts that do not offer that.

“I do say this – schools have to open,” he told host Chris Wallace. “Young people have to go to school, and there’s problems when you don’t go to school too. And there’s going to be a funding problem because we’re not going to fund – when they don’t open their schools.”

Mr Vermund said it was “disingenuous of the president to demand schools be reopened and then threaten to cut funding”, as schools with more resources would probably have a better shot of safely reopening.

Missouri Republican governor Mike Parson on Friday told talk radio host Marc Cox that kids “have to get back to school”, though he conceded that some were likely to contract the virus.

“They’re at the lowest risk possible,” Mr Parson said. “And if they do get Covid-19 – which they will, and they will when they go to school – they’re not going to the hospitals. They’re not going to have to sit in doctor’s offices. They’re going to go home, and they’re going to get over it.”

In Florida, the teachers union said in the lawsuit that the education commissioner’s order that districts must open brick-and-mortar schools, subject to the advice of state and local health departments, would “create an unsafe and unsecure environment for students, employees, and the community at large”.

“When students and employees return to the school site, they will be indoors with each other for 7 hours a day in derogation of CDC guidelines and executive orders issued across the state,” the lawsuit said. “They will be sharing common areas including buses, hallways, classrooms, clinics, locker rooms and bathrooms. They will be touching door handles and sharing equipment along with potentially hundreds of other people. These millions of individuals will return to their families and to the community to continue to accelerate the spread of Covid-19.”

The suit alleged that some teachers had rushed their retirements over the state’s plan and others were “preparing wills and living wills ahead of possible in person learning that can expose their health and lives to serious threats”.

Mr Corcoran, the Florida education commissioner, shot back that the union did not seem to have read or understand his emergency order and that even before it, state law required schools to operate for 180 days a year, which amounts to five days a week.

“This EO did not order any new directives regarding the requirements of schools to be open, it simply created new innovative options for families to have the CHOICE to decide what works best for the health and safety of their student and family,” he said in a statement.

Mr Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, said it would probably be impossible for a place like Florida – where it is believed one in 24 people is infected – to return to in-person schooling safely. Even if transmission from children to adults is low, he said, it is not nothing, and adults in the school could transmit to one another.

But Mr Jha said in other states, where fewer people are infected, schools could open with appropriate precautions. And there is good reason to do so, he said, as a lost school year brings with it serious consequences, particularly for those with lesser means.

“It’s not just the fall,” Mr Jha said. “Things aren’t going to be better in January. Things aren’t going to be better in February. They might not be better until April or May.”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments