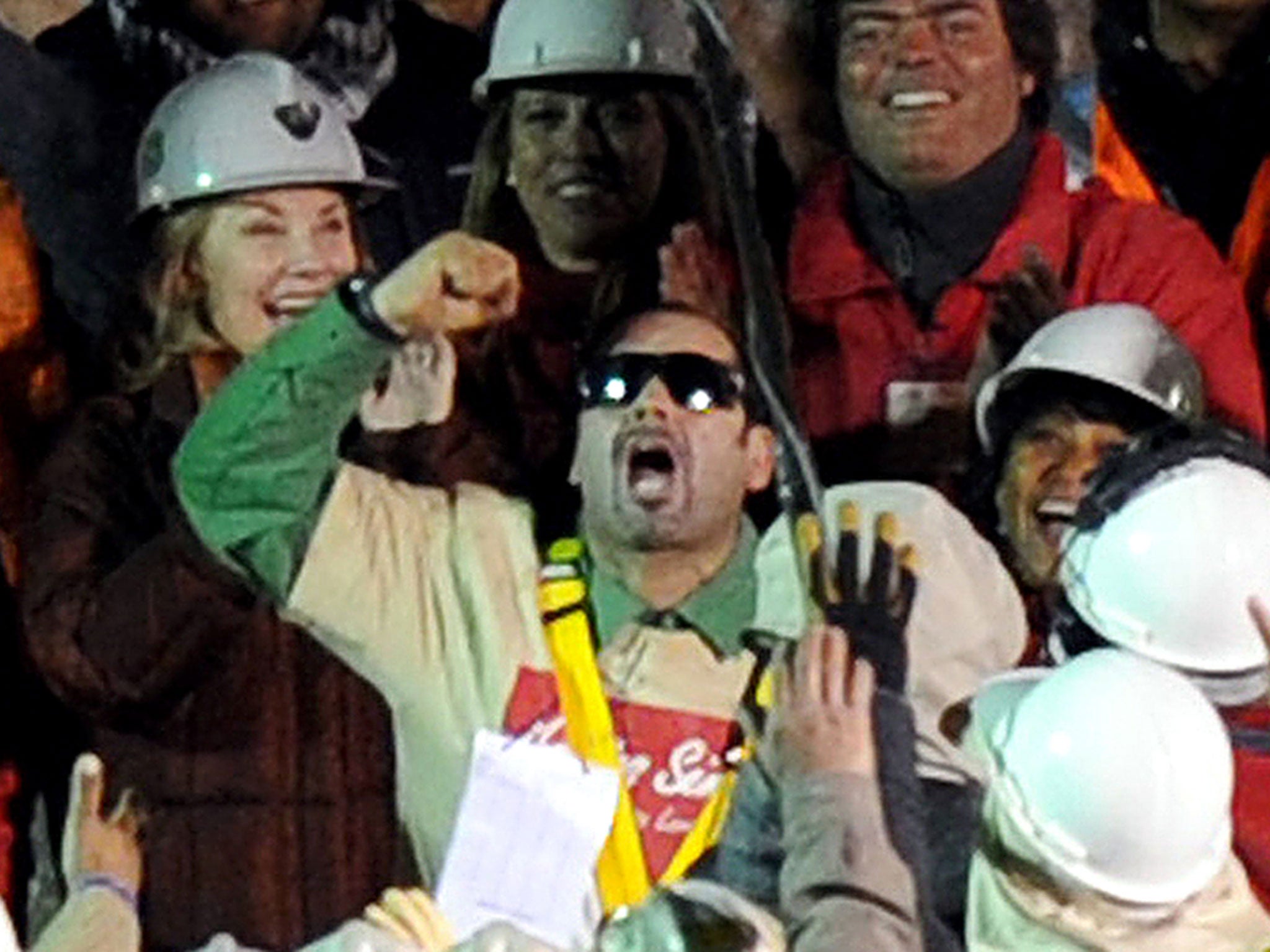

Chile's San José miners talk about their 18 days sealed in an underground hell - 'the 33 of us'

Their rescue unfolded in August 2010. But before the miners were set free, they each promised not to sell their story. Instead, they would talk to one man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The San José Mine is located inside a round, rocky and lifeless mountain in the Atacama Desert in Chile. Few sightseers visit this corner of the Atacama, though Charles Darwin did pass nearby, during his 19th-century journey around the world on HMS Beagle.

During their 12-hour shift on 4 August 2010, the miners have noted a kind of wailing rumble in the distance. The mine is “weeping” a lot, the men say to each other. They have heard these gathering storms before. The thunder always recedes and eventually the mountain returns to its steady and quiet state.

Down the mine, sea level is the chief point of reference. On the morning of 5 August, the men of the A-shift are working as far down as Level 40, some 2,230ft below the surface, loading freshly blasted ore into a dump truck. Just after 1pm, the collapse hits them as a roar of sound, as if a massive skyscraper were crashing down behind them, according to miner Franklin Lobos.

The metaphor is more than apt. The vast and haphazard architecture of the mine, improvised over the course of a century of entrepreneurial ambition, is finally giving way. A single block of diorite, as tall as a 45-storey building, has broken off from the rest of the mountain and is falling through the layers of the mine, knocking out entire sections and causing a chain reaction as the mountain above it collapses, too. The ceiling and floor become undulating waves of stone and the mountain hurls boulders that emerge from the blackness of the tunnel and roll and bounce downhill, each a lethal weapon aimed at their bodies.

“We were a pack of sheep and the mountain was about to eat us,” José Ojeda later says. They watch, mesmerised, as another blast wave rushes through the tunnel. It seems to pick up Alex Vega, the smallest and slightest of the miners, and lifts him off his feet. Others are knocked over; falling, flailing at the air.

When the turbulence dies down, Mario “Perri” Sepúlveda shines his light in the faces of the older men and sees the blood-drained look of mortal fear. They follow the lights of their headlamps and flashlights through a gravelly cloud, until the beams strike an object that appears to be blocking the way forward. It’s the gray surface of a stone slab, its size and shape not quite clear in the still swirling dust.

They sit and wait in that cloud for several minutes, for the air to turn less gravelly. As it does, the full size of the obstacle before them becomes apparent. The ramp is blocked, from top to bottom and all the way across, by a wall of rock. To supervisor Luis Urzúa it looks “like the stone they put over Jesus’s tomb”.

Only later will the men learn the awesome size of the obstacle before them, to be known in a Chilean government report as a “megabloque”. A huge chunk of the mountain has fallen in a single piece. The rock before them is about 550ft tall. It weighs 700,000,000kg, or about 770,000 tons, twice the weight of the Empire State Building.

Some of the men can already sense the enormity of the disaster.

“Estamos cagados,” one miner says. Loose translation: “We’re f***ed.”

“We have to break it open!” one of the men calls out. “We’re hungry.” The cabinet around which they are gathered that evening is supposed to contain enough food to keep 25 men alive for 48 hours in the event of an emergency. Many of the men haven’t eaten since dinner the night before, to avoid the vomiting caused by working underground in intense heat, humidity, and dust-filled air.

Lobos opens the cabinet and the rebellious miners’ main object of desire is revealed: packages of cookies with the brand name Cartoons. They’re really children’s snacks; chocolate- and lemon-flavoured sandwich creams, several dozen packages in all. There are four cookies in each package, several of which are quickly dispensed to those who will take them, though many miners refuse.

Later, one of the miners will remember listening to the looters of the food box eat in the darkness, sitting in a corner with their headlamps off, as if they were ashamed of their own hunger and yet unable to keep the crackle of crumpling plastic and the moist crunch of their chewing from filling the small space, to be heard by men who did not take any food at all.

Sepúlveda helped to take an inventory of the remaining emergency provisions: one can of salmon, one can of peaches, one can of peas, 18 cans of tuna, 24l of milk (eight of which turned out to be spoiled), 93 packages of cookies, minus the ones that had been eaten, and some expired medicines.

There were also 240 plastic spoons and forks, but only 10 litres of bottled water. The miners figured that if each man ate one or two cookies and a spoonful of tuna every day the provisions might last a week. There were thousands of litres of water stored underground in tanks, but the water was used to cool the industrial machinery and it was tainted with oil.

Urzúa counted the men again, checking the list against his mental notes on how many men should be there.

“There are 33 of us,” he announced.

“Thirty-three?” Sepúlveda shouted. “The age of Christ! Shit!”

Several other miners repeated the phrase: “The age of Christ!” Even for men who weren’t especially religious, the number carried significance. Normally, there would have been only 16 or 17 of them, but because many were working overtime, or make-up days, there were twice as many – so many that no one man had met all the others.

Finally, Sepúlveda spoke, raising his voice so that everybody could hear.

“There are 33 of us,” he said. “This has to mean something. There’s something bigger for us waiting outside.”

Several times during those first days, the mountain rumbled as though it were exploding again. A few of the men took the stretchers and used them as beds; others put cardboard onto the tile floor.

The men were covered in soot. Without any ventilation, the area started to smell like their fetid, unbathed bodies. One miner said: “I’ve smelled corpses before and after a while it smelled worse than that.” The few litres of bottled water were finished in a day, so the men drank from the industrial water in the tanks.

Sepúlveda organised the men into teams and every two days they drove a vehicle to a tank, to fill a 16-gallon barrel. Before the collapse, the men would rinse their dirty gloves in the tanks. Sepúlveda had sometimes jumped in to take a bath. A few men pointed out that they were drinking his bathwater. When they shone their weakening lamps on the water, they could see a black-orange film and drops of motor oil. That water was keeping them alive.

The hunger hit them most painfully during the first few days. They could not defecate and the emptiness in their stomachs felt like a fist pushing downward. Mario Gómez, at 63 the oldest member of the group, was in bad shape. He had silicosis and his incessant cough conveyed history, as if it were something transmitted by his grandfathers, who were miners. José Ojeda, a 47-year-old widower, was diabetic. Would two cookies a day keep him from going into shock? Jimmy Sánchez, at 19 the youngest of the miners, was acting like an old man. He wouldn’t get up and his lethargy was beginning to spread to other men.

Victor Segovia began keeping a diary on the back of forms used to monitor the vehicle he operated. He wrote: “There is a great sense of powerlessness. We don’t know if we are being rescued or what is going on outside because down here we don’t hear any noises from machines or anything.”

Segovia had been expelled from school in the fifth grade, but he wrote with stark clarity. At 3.30am on the third day, he began with a note to his five daughters: “Girls, unfortunately destiny only allowed me to be with you until the fourth of August. I am weak and very hungry. I’m suffocating... it feels like I’m going to go crazy.”

The men began to listen obsessively for the sound of rescuers. Barrios said that, with your ear to the stone, “it was like listening to the inside of a seashell. You heard nothing and you heard everything. You could imagine an ocean roiling inside that shell and then you realised that it was all an illusion”.

At 7.30pm on 8 August, about 78 hours after the collapse, Segovia noted in his diary the sound of something spinning, grinding and hammering against rock.

For three hours, the roar grew steadily louder. It was unmistakably a drill, the sound travelling through 2,000ft of rock.

“Do you hear that, you bastards?” Sepúlveda shouted. “What a beautiful noise!”

Someone said that a drill could advance at 100m a day. At that rate, the drill might break through in five or six days.

On 15 August, their eleventh day underground, Segovia noted in his diary: “It’s 10.25 and the drilling has stopped once again. I really don’t know what’s going on up there. Why so many delays?” The next day, Segovia wrote, “Hardly anyone here talks anymore.”

Then, on 17 August: “They are starting to give up... I don’t think God would have saved us from the collapse just to let us die of starvation... The skin now hugs the bones on our faces and our ribs all show and when we walk our legs tremble.”

The drilling continued, but intermittently. After a day, it seemed to be getting closer and the men prepared for a possible breakthrough. They found a can of red spray paint, used in routine mine operations. If the drill bit broke through, they’d leave a mark on it with the paint and when the bit was lifted up it would prove that there were survivors below.

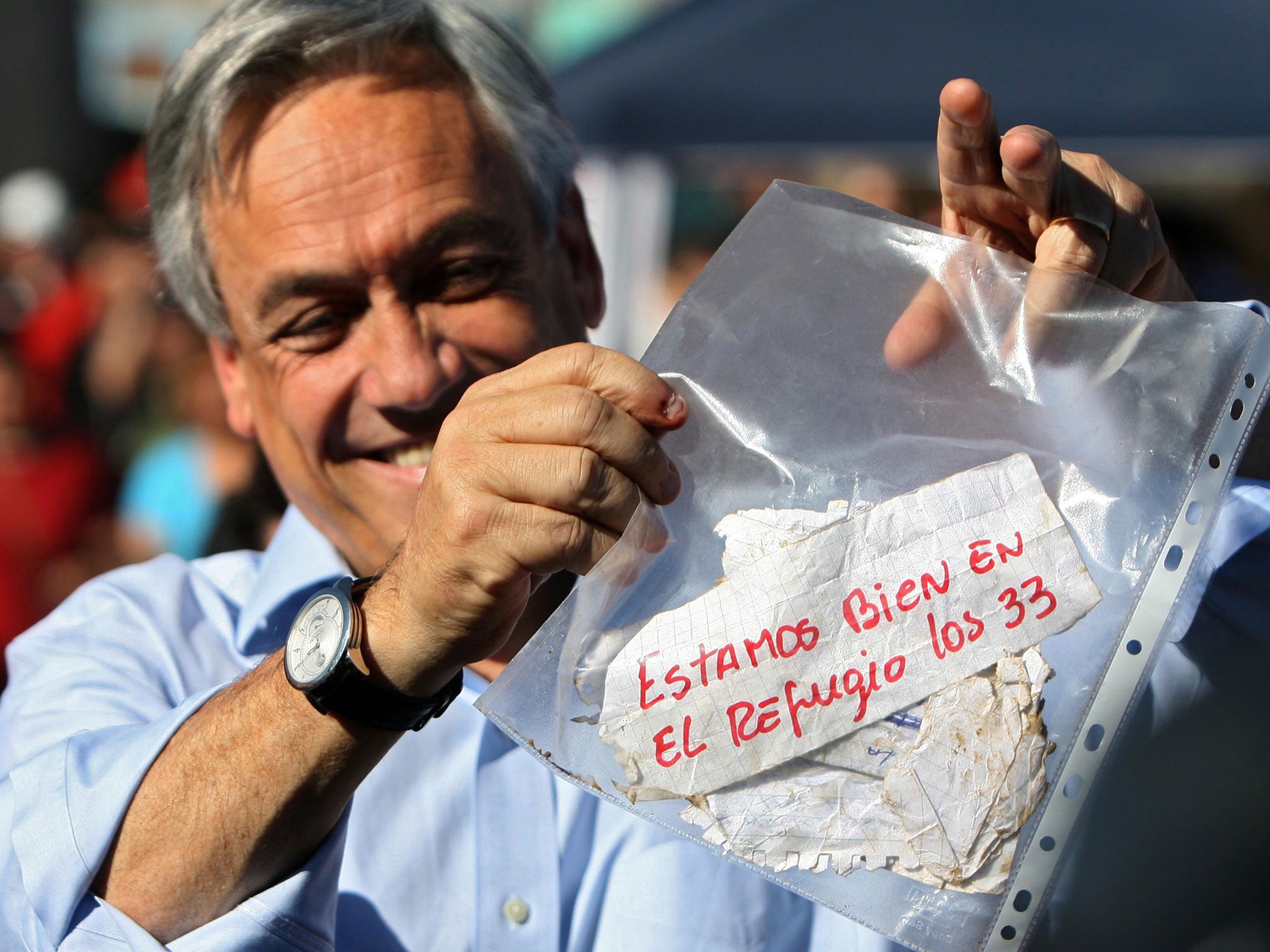

José Ojeda, who had remained alert despite his diabetes, explained that he had been taught to include three pieces of basic information in any message for potential rescuers – the number of trapped men, their location and their condition.

With a red marker and a piece of graph paper, he wrote such a message, boiling it down to seven words: “Estamos bien en el refugio los 33.” We are well in the shelter, the 33 of us.

After another day, it became clear that the drill had passed beneath them and they tried to follow its sound, going lower and lower until it faded away.

On 19 August, Segovia wrote,“The drill does NOT break through,” and on the 21st: “I’m beginning to wonder if there’s a black hand up above that doesn’t want us to get out.”

Sometime after 5am on 22 August, Sepúlveda woke up from a dream at the command of his dead grandfather. The almost euphoric feeling of having seen his grandfather stayed with him as he took in the grinding and pounding sound of a drill that had become impossibly loud.

“It’s going to burst through,” says José Ojeda, in a matter-of-fact voice. The grinding of metal against rock that has filled the ears of the men stops and in its place there is a whistle of escaping air.

Richard Villarroel, an expectant father, watches as a drill bit inside the pipe lowers and rises and lowers again. Soon, all 33 men have gathered around the pipe and the drill bit, objects that have intruded into their dark world with the promise of raising them up to the world of light again.

With its parallel circles of pearl-size tungsten carbide teeth, the drill bit resembles some Assyrian sculpture; a kind of alien apparition, and the men stare at it in awe and joy, embracing and weeping. To Carlos Mamani, who falls to his knees before the drill bit: “It felt like a hand had punched through the rock and reached out to us.”

José Henríquez, the jumbo operator who’s been transformed underground into a shirtless and starving prophet, looks at the drill bit and pronounces the obvious to anyone who will listen: “Dios existe,” he says. God exists.

Deep Down Dark, by Héctor Tobar (Sceptre, £20), is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments