Magnitude won’t be the horror determinator of California’s big earthquake — location will be

Earthquakes remain confoundingly difficult to predict, according to experts, even though many are desperately trying to figure out the best way to handle big quake in a state encountering around 35 a day, writes Josh Marcus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

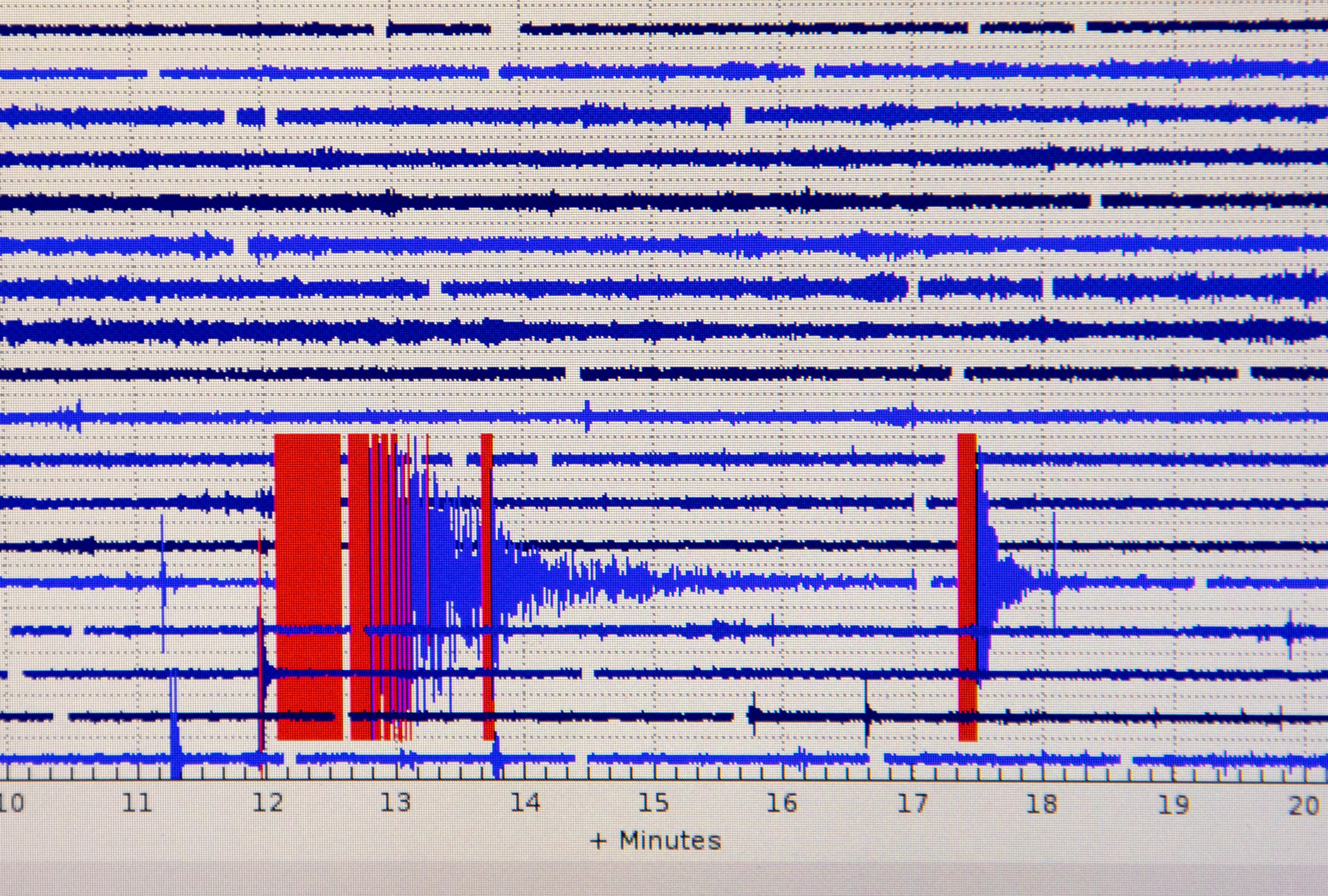

Your support makes all the difference.In recent days, Southern California has experienced one earthquake after another. A 3.6 in Ojai on May 31. Two of a similar magnitude under the East Los Angeles area of El Sereno. Another three quakes near Newport Beach and Costa Mesa.

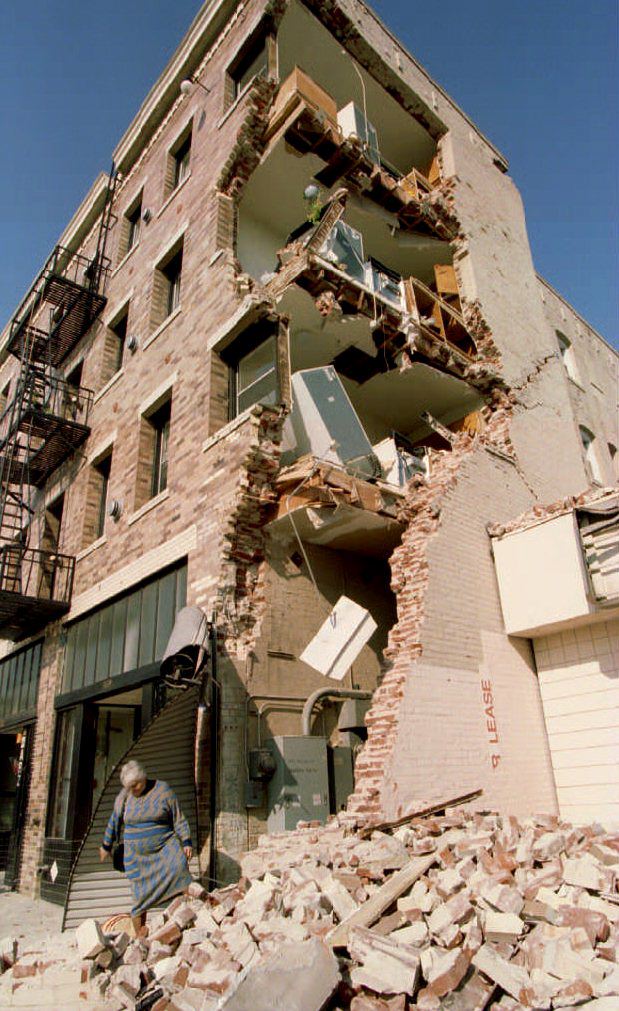

While these quakes were far weaker than historic temblors like the 6.7 Northridge Earthquake of 1994, which caused an estimated $20bn in damage and killed over 57 people, do they herald the arrival of the so-called Big One in a state sitting on multiple, highly active faultlines?

There’s the notorious 800-mile-long San Andreas, which runs from near the Mexico border, east past Los Angeles, then up the coast north of Sacramento.

Major quakes occur along the fault every 180 years or so, and the San Andreas hasn’t had a majorly powerful one since 1906. The US Geological Survey estimates it has a 60 percent chance of causing a magnitude 6.7 or greater in the Los Angeles area in the next 30 years.

Of even greater concern is the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which runs from Northern California to British Columbia, Canada. It’s overdue for an even larger quake compared with historical averages.

So, are the recent earthquakes an ominous omen of something larger, or business as usual in a state with an estimated 35 quakes a day?

The El Sereno quakes, for example, happened just under the Puente Hills thrust fault, which runs beneath downtown Los Angeles and Orange County. The 10-mile deep fault angles like a ramp and gets closest to the surface near the LA campus of the University of Southern California. If a quake along this fault hits the loose earth of the Los Angeles Basin, it could amplify the intensity of an earthquake by up to ten times compared to areas located on bedrock.

The Newport Beach-Costa Mesa temblors, meanwhile, took place near the Compton thrust fault, which could raise the LA River by up to 5 feet in a strong quake, wreaking havoc on city sewer systems. There have been six quakes above magnitude 7 along the fault in the last 12,000 years, according to geologists.

Scientists argue that instead of focusing solely on the largest quakes by magnitude, the key consideration is how much damage they could do to densely settled areas. The San Andreas, despite its famous reputation, runs for large sections through sparesly populated desert.

“In some respects, the ‘big one’ in terms of damages and deaths would be ones running through town rather than one that’s a long distance away,” Dr. Pat Abbott, professor of geology emeritus at San Diego State University, told KSWB last year. “There’s the size of the earthquake, and then also where you are situated compared to where the fault’s moving.”

He pointed to major quakes like the 1857 and 1906 San Andreas earthquakes, as well 1994’s Northridge earthquake, all of which were under the 8.0 magnitude contemplated in “Big One” scenarios but which still caused “horrendous” damage.

“Unfortunately, earthquake prediction remains an extremely challenging endeavor,” according to the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services website. “While scientists can monitor fault lines and detect patterns of seismic activity, they cannot predict exact earthquakes reliably.”

Instead, scientists deal more in the realm of long-term probability, which can inform what high-risk areas can do to prepare for the day when the hard-to-predict prospect of a major quake arrives.

For instance, the USGS estimates that there’s a 72 per cent chance a 6.7 or greater magnitude quake will hit the San Francisco Bay Area in the next 30 years.

Finding a greater level of precise prediction is the “holy grail” of earthquake science, University of Washington seismologist Harold Tobin wrote last year.

“Science has not yet found a way to make actionable earthquake predictions,” he wrote. “A useful prediction would specify a time, a place and a magnitude – and all of these would need to be fairly specific, with enough advance notice to be worthwhile.”

In the meantime, until that magic predictor code is unlocked, governments can push for preparedness measures like digital alert systems, practice drills, and building retrofits, while individual citizens are advised to have emergency kits in place and drop to their knees, cover their head and neck, and hold onto something stable when a quake begins.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments