The brains behind Bluey: He turned a simple kids’ show into a global hit. Now he’s ready to walk

Almost everything about Bluey – from a real-life blue heeler to games played by characters – stems from the personal experience of creator Joe Brumm. He talks to Sheila Flynn about the cartoon’s runaway success across the globe and how fatherhood helped shape the show

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Joe Brumm was working in children’s television in the UK, he identified a gap in the market in his native Australia. He wanted to create a show similar to Peppa Pig but with an undeniable Aussie flavour – a programme focusing on the benefits of play for children and parents, a short cartoon with witty, relatable scenarios.

He nailed it with Bluey, which has taken the world by storm with its adorable plot lines featuring blue heeler pup Bluey, her little sister Bingo and their parents, dad Bandit and mom Chilli.

After debuting in Australia in 2018 to wild success, the show was licensed abroad by BBC Studios and broadcast by Disney - similarly resonating internationally with parents and children alike.

The show has not only raked in awards but also earned praise for its portrayal of family values and parenting – particularly by Bandit, the archaeologist father who is heavily involved in his pups’ life and play. Bluey will soon be releasing its full third season.

But Mr Brumm, 43 – who has modelled much of the show on personal parenting experiences as the father of two girls – says his days in children’s television may be “limited”.

His success in youth programming wasn’t even part of his plan in the first place, Joe Brumm tells The Independent.

“I never, ever saw myself working in children’s television,” Mr Brumm says: “It doesn’t suit me very well.

“I think it’s got a lot of challenges, and ... the nature of it is that you make stuff and then ... it just gets edited and chopped and changed, things taken out.

“Because [it’s] children’s TV ... people you give it to sort of think that’s appropriate,” he says of the editing process. “I can’t handle that so well – so I think my days working in it are probably a bit limited.”

Parts of the show have been changed since it left Australia, he adds – citing a use of the word “thong”, which In Oz refers to sandals but in other countries means women’s underwear.

“Little things like that, which on the surface are understandable ... from my point of view, I think it’s inexcusable and it ruins the flow of my show,” he says. “That’s their right to do, but as a filmmaker, it’s not the same.”

He says he wants “to go back to what I always thought I’d be [working in] which is adult animation,” he says – believing the switch would give him a lot more “freedom”.

Mr Brumm cites adult animation series The Simpsons as one of his career inspirations that, to some extent, helped the emergence of Bluey as he noticed gaps within the children’s programming market.

“Shows that have got real heart to them are in the minority in the kids’ TV space,” he tells The Independent.

“Kids can follow good stories,” he adds – but he didn’t see too many shows with heart, plot and the ‘it’ factor that can truly engage diverse audiences.

The evolution of Bluey

Mr Brumm, born in Queensland, grew up as a middle child sandwiched between an older and younger brother. The family, which eventually moved to Brisbane, kept several dogs – including a blue heeler named Bluey. (The breed are known as Australian cattle dogs in the US.)

He attended Griffith University in Queensland and spent 10 years working as an animator in the UK, contributing to shows such as Charlie & Lola, before returning to Oz. He and his wife, Suzy, who also works in television, welcomed two daughters to their family. That’s when the ball really got rolling for a show that would unexpectedly take off across the world.

“I really like Peppa Pig, and it was the top of the heap of those shows” in the UK, he says. “I really liked how it just told very simple, relatable stories about kids that had a real sense of being from the UK – so I wanted to do something that had a real sense of being from Oz.”

He says: “I want to make a show that people can watch as a family ... something like The Simpsons did, where you could watch it as an adult or maybe an eight or nine-year-old. I wanted something you could watch as an adult and also a four-year-old, which is quite a step – and it changes the nature of the show.

“But I thought, ‘There must be a lovely little thing ... that you really share when a four-year-old sits down with their parent and both actively enjoy watching the show.’”

As he brainstormed, he remembered his dog Bluey – though the pup initially was not the eponymous character on the show.

“It was originally a kelpie, because that was the last dog I had through my teenage years,” the filmmaker says, though that Australian breed is not known for “vivid colouring”.

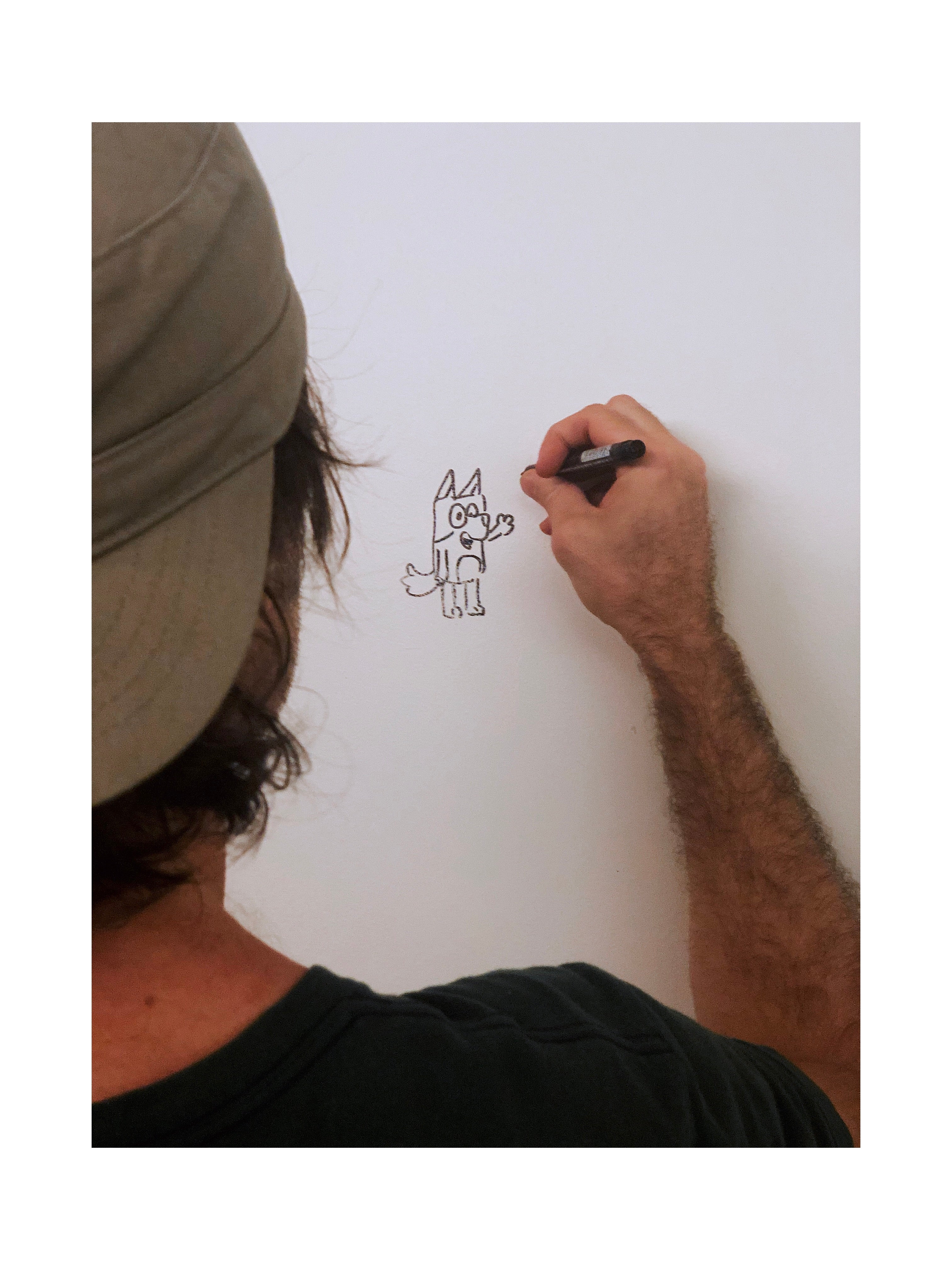

“I drew a little friend as a blue heeler,” he says. “I just kept returning to this bright blue dog – and I thought, this is kids’ TV. We need bright colours. And I used to have a dog that was a blue heeler called Bluey growing up, so she just sort of supplanted ... the kelpie.”

“It was perfect, because then you can have red heelers, as well – so you’ve suddenly got your little sister,” Bluey’s puppy sibling, Bingo.

Mr Brumm’s own two siblings have played a major part in the breakaway-hit show. His other brother, an archaeologist, inspired the profession for Bluey’s father – and had lobbied for a different type of canine-themed show before Bluey evolved, Mr Brumm explains.

“My older brother is an archaeologist,” he says. “Sort of before Bluey, he would always pester me: ‘Look, man, I’ve got this idea for a cartoon – this dog is named Professor Fleagle, and he’s an archaeologist, and he likes digging up bones.”

Mr Brumm continues: “When it came time and I made [Bluey] and I needed to give Bandit a job, Professor Fleagle just came into my head.”

His younger brother, Dan, voices Bluey’s Uncle Stripe and “also works and does sound design on the show”.

How personal experiences – and the benefits of play – shaped Bluey

It’s undeniable that the production of Bluey, to some extent, is a family affair; in addition to the inspiration from Mr Brumm’s older brother and the involvement of his younger sibling, his wife also works on the programme.

And the couple’s experiences with their own young children provided easy fodder for the short episodes with plot lines that are instantly recognisable to any parent.

“The thing that really started standing out, when it came time to write the show, was I was spending a lot of time, early morning, playing with my kids. And a lot of games would be mainly role-playing games. They would be a café owner and I would be the customer, or I’d be a patient and they’d be a doctor, or I’d be a kid and they’d have to put me to bed or vice versa.

“And a lot of these games would just end up in these really weird, bizarre places, because they didn’t quite know how cafes worked and ... would just sort of make up their own rules and words. It was endlessly fascinating to them and absorbing to them, but it was really quite funny to me, as well – just like being in a Monty Python sketch, where you walk into a café and you’re a completely normal customer, but it’s a bit of a bizarre world.

“I thought, that’s a good opportunity to show games that kids will really love but are also really funny for parents to watch and relatable.”

He became particularly interested in the research of play and its role in childhood development.

“I learned more and more about play, and then ... that became the bulk of the show – really just those sort of role-playing, imaginative games that kids four to six play.”

‘Kids do learn ... a hell of a lot while they’re playing – and especially while they’re playing with their friends or siblings in these games.

“It’s where they’re practicing to be adults. It’s where they’re learning to share and it’s when they come out of that age three or four, into four, five, six, they’re learning to just get along – because if they don’t, the game grinds to a halt.

“So I think – I hope – the show does impart that it’s not just frivolous, it’s not a waste of time, and that play across all ages (but particularly that age) is ... an incredibly fascinating thing to think about, play and its role in our species and our day-to-day lives and the relationship it has to work and all those things.”

Bluey’s journey to international phenomenon

Bluey almost instantly became popular with Aussie audiences in 2018; a year later, BBC Studios secured the global licensing rights, Disney worked out a broadcasting deal and the show debuted abroad.

“It was when Disney bought it, I thought that was a real moment of like, ‘Okay, Americans get this,” Mr Brumm says. “Because it just wasn’t a given. There’s not even a slight inkling to me to hide the Australianness in it.”

He adds: “It was very gratifiying, very heartening, when Disney took it on - and then when we started getting feedback come through from American viewers that it didn’t bother them that it was so local, I guess, they were obviously just seeing what the heart of the show was - which is just parents trying to raise kids and the beautiful little world that kids live in.”

The show hit American screens in 2019, first on Disney Junior, and episodes of the first two seasons can now be viewed on Disney+. Some of the third season has already aired in Australia but no date has been announced yet for its availability in other countries.

Despite small cultural differences and vernacular, non-Australian audiences went wild – and that includes parents watching with their children. Much of that stems from the relationship between Bluey, her parents and their friends.

“We had one of the strongest reactions we’ve ever had to any show that we’ve been involved in,” said Henrietta Hurford-Jones, BBC’s head of children’s content, after the broadcaster’s acquisition of rights. “Everybody wants it but Disney really leant into it.”

Following the show’s debut on Disney Junior in October 2019, the channel reported 16million viewers in the final quarter of the year. That audience has expanded exponentially since it began streaming on Disney+ in early 2020 - and just a few months later Bluey won an International Emmy Kids Award.

Hand in hand with the show’s popularity came merchandising deals. By June 2020, one million Bluey books had been sold in Australia. Before Christmas 2021, Bluey toys and products were among the most sought-after items in America for children’s presents.

Bluey has been shortlisted for the License of the Year by the Toy Association, the New York-based trade association which will hold its annual awards ceremony next month. The category recognises the “biggest brand in the toy space,” spokeswoman Kristin Morency Goldman tells The Independent.

The show is up against heavyweights like Barbie, Paw Patrol and Pokemon.

“I think that really indicates how big Bluey is in the toy world ... how quickly Bluey has blown up and how popular it is, that it has already been nominated for Licence of the Year.”

Multiple new licensing deals have also been announced recently for merchandise in other countries, further expanding the brand’s recognisability, reach – and financial gain.

“We’re going to be seeing a lot more Bluey toys,” says Ms Morency Goldman, whose own children are fans. “There’s certainly a buzz around Bluey.”

Bluey’s parenting portrayal: Idealistic or unrealistic?

As Bluey went from strength to strength, gaining millions of fans across continents, the conversation about its depiction of parenthood grew with equal abandon. A quick conversation on the playground or a passing glance at any parenting forum online would confirm as much within seconds.

The programme has been lauded for subverting gender norms and outdated familial tropes while appealing as much to adults as kids with its wit, relatability and catchy music. Some have called Bandit their father idol; others have lamented that the standards of parenting are almost too lofty to replicate in real life.

Bandit, particularly, has been held up as an ideal of fatherhood. While he’s forged a career in archaeology, Bluey’s mom, Chilli, works in airport security. But they’re happy to join their children on fanciful journeys, taking time out to indulge play and expand their pups’ imaginations.

“What I like about Bluey is it makes me want to be a better father,” one Australian, married to an American in Colorado, tells The Independent.

“The dad in Bluey puts all dads to shame,” musician and author Tom Fletcher tweeted. “He’s my dad-idol.”

Much of that adulation stems from Bandit’s willingness to not only play with his pups but also show or admit imperfections. He’s something of a modern-day model for fatherhood.

But putting the cartoon father on such a high pedestal creates impossible expectations, others argue.

Mother and Independent columnist Danielle Campoamor wrote that the show is “making parents like me feel like sentient garbage”.

“On Bluey, the mom and dad do nothing but play elaborate make-believe games with their children — an utter impossibility in the era of pandemic parenting, where we’re more likely to stick a tiny screen in front of our children’s faces just so we can use the bathroom in peace than spend our precious time and brain juice playing ‘finding fairies’ or ‘keepy uppy’ or whatever imaginative, lesson-based game this show continues to peddle’” she wrote.

Mr Brumm, for his part, is often assumed to be the model for Bandit – but he insists that’s not the case.

“Bandit’s more of the sort of idealistic, in a lot of ways, dad – whereas Stripe is probably more accurate with my actual fathering.”

He also wants to be clear that he’s not setting out to make a show that’s “pontificating” or preaching.

“I’m never trying to teach anything, especially not to the adults and definitely not the kids.

“Just sort of putting that up there, fairly honestly, is what people are connecting to,” he says. “It’s not about them getting browbeaten by my views on the world; it’s just sharing my experience – and I think that’s probably the thing that, as a parent, you do sometimes feel – like you’re the only one going through this.

“And then this moment when you do connect with someone and realise this is normal and they go through that too ... [those] are usually the moments that cut through the most. And that’s sort of what this show is about.”

The influence of Bluey on children’s accents – and attitudes

It’s not remotely surprising, given Bluey’s popularity, that countless North American children have begun adopting phrases and inflections from the show.

Parents across America have reported their children using terms like “brekky” and “dunny”. A similar trend emerged with the rise in popularity of Peppa Pig.

For Bluey’s creator Joe Brumm, the phenomenon is amusing – and a nice antidote to the Americanisation of Australian TV.

“All I can do is apologise,” he laughs to The Independent.

“What’s been quite nice is the American audience, in particular ... they’re enjoying the little puzzle of trying to figure out what half of the words mean.

“I think audiences, and especially kids, can find a lot of enjoyment out of those little puzzles – figuring out that, oh right, this same English-speaking country calls these things a different word. They call ‘sidewalks’ ‘footpaths.’”

While Mr Brumm says his career may veer from children’s television, he tells The Independent he’s thrilled with the show’s popularity and global resonance, though he maintains that connecting with young viewers remains his focus – and he tries “not to think about impact or anything like that” too deeply.

“Part of my job is just keep the show funny and keep it entertaining – and everything else has to fall by the wayside,” he says.

He’s pleased by the reaction from other parents, who “definitely want to come and tell you what their favourite episode is and talk to you about the show,” he says.

“So that’s been quite sweet ... [some parents] on occasion tell me how much the show means to them; maybe they don’t usually let their kids watch TV, but they let them watch Bluey and they watch it all together.”

He does, however, hope Bluey affects a new generation of viewers the same way cartoons influenced him as a child – leading to this latest phenomenon in children’s TV.

“When these kids who are growing up on Bluey now are in their 20s and 30s and 40s, if someone asks them: ‘What was the cartoon you liked as a kid?’” and they answer “Bluey,” Mr Brumm says, “That’s the highest compliment that I could get – because I know I still vividly remember the best cartoons that I watched as a kid. And they inspired me.

“That would be a great thing for me if that was the case.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments