Violent sting ops, wasted millions, and an unbothered Biden: The crackdown on homeless people on federal lands

As housing becomes unreachable, homeless people are flocking to America’s sprawling public lands, but federal agents seem unprepared to address a complex issue without resorting to violence, Josh Marcus reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.America is land rich and housing poor.

Within the US, already the third largest nation in the world, is a country within a country, 640m acres of vast, largely uninhabited public lands. At the same time, cities are struggling with homelessness and median home prices in 99 per cent of US counties are out of reach to the average buyer.

As the home ownership part of the American Dream becomes more of a fantasy, untold numbers of citizens have taken to living in Forest Service woods, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wildlands, and remote trailheads in wild areas across the country. They are hoping for a safe haven and a bit of peace in a country that makes it exceptionally difficult to find and keep a stable home unless you are rich or lucky.

Up against this growing phenomenon, the federal agencies in charge of managing these lands – the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior, neither of them primarily police nor social service agencies – have at times been outmatched by the complexity of encountering unhoused people and helping them in an effective, safe way while upholding the law.

In the case of one Idaho family, rather than offer aid, the Biden administration invested huge resources in a violent sting operation that left an already disabled man paralysed.

The Roberts family was living on the edge long before police knocked at their door. Judy Roberts of Emmet, Idaho, was the sole source of income for her two adult sons, Brooks and Timber, both of whom have disabilities. In March of 2020, shortly after the pandemic began, she was injured in a car accident and lost her job at a manufacturing plant. Soon the family was evicted from their rental home.

“They had nowhere else to go,” Craig Durham, a lawyer representing Brooks, told The Independent.

Unable to afford somewhere new, the family began camping in the ample public land outside of Boise. Soon, they caught the attention of federal agents from the BLM and Forest Service, who began warning the family they had to move, as most federal lands outside of national parks only allow camping for two weeks at a time.

As the warnings piled up, the family had to keep seeking out new places to live that weren’t in a 25 mile radius of each other to avoid running afoul of the authorities. As the Roberts family shuffled from one place to the next, homeless and jobless, they lived in a small camper and for a time an old school bus.

“They eventually kind of ran out of new spots to go to,” Mr Durham added.

By the fall of 2021, the family was living in a spot called Black’s Creek, in the high desert outside of Boise. Heavy snows trapped the Roberts family in the location all winter, and Judy’s frostbitten feet froze to the floor of the school bus. By the time she made it to a hospital, she was hallucinating. Doctors had to amputate both her feet.

During this period, a US Forest Service officer had a tense encounter with the family, details of which later described in federal court documents.

“Timber continued to yell at and scream about how he was being harassed” the Forest Service employee wrote. “At that point he was beginning to go back into the camper, and I did not feel safe with his current state of anger having access to the vehicles. I yelled at Timber, to stop and not to go in the vehicle.”

The officer also described the conditions the family was living in.

“The camp was in disarray with two dogs tied up to trees in the camp with feces all around them, there was trash surrounding the vehicle and camp area,” the officer wrote. “There was also a truck bed made into a trailer that was overflowing with trash and debris. The trash and debris were spreading towards the creek.”

As Judy convalesced, tragedy was again on the horizon. To supplement Judy’s meagre Social Security income checks, Brooks got a job working overnight at a Walmart. In June 2022, he suffered a workplace accident that put him in a wheelchair.

As the Roberts family went from harsh snow to blistering summer heat at Black’s Creek, the BLM was continuing to urge them to go somewhere else, so the family vacated the area in October of that year.

With few options left, they fled further afield to the West Face Trailhead, a remote mountain site in the federally administered Payette National Forest near the Oregon border.

In February of 2023, the family was charged with multiple misdemeanours for overstaying on public lands for previous camping. That spring, Timber was charged with interfering with a federal agent, and accused of threatening members of the public.

The US Attorney’s Office then hit the family with another round of charges for staying at the West Face Trailhead. The charges against the Roberts family were low-level, the kind of misdemeanour offence that rarely even results in an arrest, though federal officials said they worried that because the family owned guns and had received complaints they were an “immediate danger to the community and law enforcement,” according to court documents obtained by KTVB.

By this point, outside advocates were finally catching wind of the case. As a result of the first set of charges, the Roberts family received a court-appointed lawyer. Their attorney became worried that the federal government was preparing to bring its full weight down on a family in an extremely vulnerable position.

The lawyer reached out to the National Homeless Law Center, which asked the Department of Justice and US Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) to look into the case. Last year, the Biden administration laid out a plan to tackle homelessness that emphasised providing social services over hardball law enforcement tactics, and the administration has vowed to “combat” policies and “laws which criminalise homelessness.”

The lawyers thought this stance would be enough to finally get the Roberts family a break. Instead, the government was preparing to send in the cavalry.

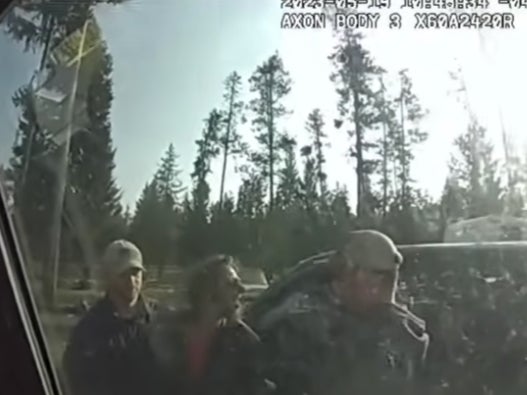

On 19 May, a ring of law enforcement officers crept secretly towards the Roberts family’s mobile home. Rather than work with the family’s existing lawyer to arrange a surrender, or knock on the door with a warrant, officials had decided on a different approach.

The Forest Service, BLM, Idaho Fish and Game, and the Adam’s County Sheriff’s Office allegedly devised a plan to pose as stranded motorists so they could lure the family out and make arrests.

Body camera footage appears to show two plainclothes Forest Service officers knock on the Roberts’ trailer and ask for help jump-starting their truck, as another officer watches on, audibly giggling, hiding in the back of a vehicle. Court documents identify the officers carrying out the ruse as Noel Rupel and Erik Franke.

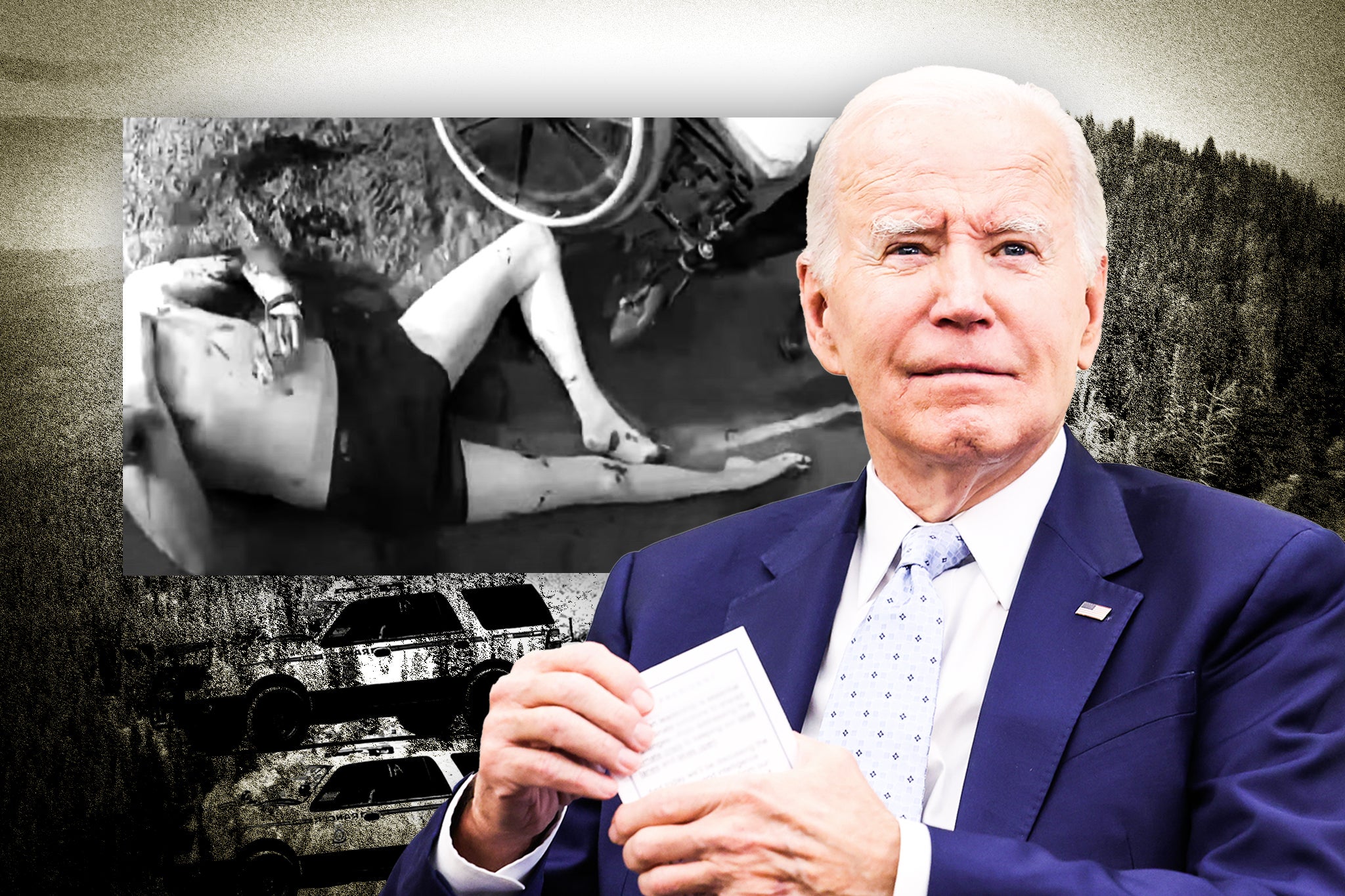

Timber Roberts emerges first. Officers inform him he’s under arrest and pin his arms to his back. His screams for help attract the attention of Brooks, who wheels out of the trailer in his underwear holding a pistol.

As Brooks approaches his handcuffed brother, sirens go off and officers begin screaming Brooks has a gun. Officers don’t tell Brooks to put down the gun, the footage appears to show, before quickly firing at least 10 shots at the wheelchair-bound Brooks.

“I’m sorry, I thought my brother was being attacked,” Brooks, shirtless and covered in blood and mud, later tells officers. “You didn’t give me a chance to put the gun down. You just f***ing shot. I didn’t know you guys were cops.”

Brooks was paralysed from the waist down as a result of the shooting, and he and his mother are now living in a motel. Now Brooks is preparing to potentially bring a $50m tort claim against the agencies involved in the sting. He no longer has control of his bowels and may never be able to work again.

The FBI is currently investigating the incident and has refused to comment during the process.

In August, Timber Roberts pleaded guilty to illegally overstaying on federal lands, interfering with a Forest Officer, and assault on a federal officer. In late September, Brooks Roberts signed a plea agreement admitting to improperly disposing of garbage and occupying a recreation site on federal lands. He will have a hearing later this month. Last week, Judy Roberts formally accepted a plea deal for overstaying on Forest Service lands in exchange for a time-served sentence.

The Independent has contacted the White House, Idaho Fish and Game, the Adam’s County Sheriff’s Office, and the USICH for comment.

The Forest Service said it couldn’t comment on the May shooting or criticisms of the operation because of pending legal matters associated with it.

“Forest Service Law Enforcement Officers use de-escalation training and Crisis Intervention Training to recognize signs associated with people in crisis that may prompt a mental health referral,” the agency told The Independent.

The BLM told The Independent it couldn’t comment on the May shooting due to pending litigation, but said its agents are highly trained and provide illegal campers with information about services and applicable federal laws, “passing on information geared to help the un-housed.”

“BLM law enforcement professionals are highly trained, with yearly refreshers to ensure officers consistently act with professionalism and compassion,” the agency said. “While each encounter is different, routine training provides officers with the skills and knowledge they need to stay safe and communicate effectively.”

Housing advocates say the sting operation was a calamitous use of federal resources, and a sign the federal government needs to take a different, more thoughtful approach to unhoused people living on federal lands. Homelessness, they say, isn’t a problem that can be solved at the end of a gun barrel.

“They must’ve spent hours planning this and if they were putting the same energy into planning how can we get this family out of homelessness, they would have achieved their goal of not having this family need to be camping out at this parking lot,” Eric Tars, legal director at the National Homelessness Law Center (NHLC), told The Independent. “Instead they were just putting it into this ridiculous law enforcement approach that didn’t actually solve the problem.”

“If you add up all the salaries and the gas for driving all of these vehicles out to this remote parking lot, the money for all the time they spent planning and all the time they’re going to have to go through in court afterwards, this family could’ve been housed for a year,” he added.

Instances like these, and the forcible eviction of numerous homeless people living on federal park land in Washington, DC, earlier this year, inspired the NHLC to call on the Biden administration to issue an executive order outlawing the use of police-like federal law enforcement agents on homeless people.

“I’m not aware of what training they’re receiving, if any,” Mr Tars said of federal officers encountering homeless people. “Based on the behaviour of the Forest Service and BLM officers involved in the Idaho incident, the most I can say is that training, if they received it, is not effective.”

The Idaho United States Attorney’s Office told The Independent it couldn’t comment in-depth on the process behind bringing the charges against the Roberts family.

“Our job at US Attorney’s Office is to evaluate law enforcement reports and bring appropriate charges to enforce the law and that’s what our office did in this particular case,” a spokesperson said.

The official added that the charges “reflect the crimes that were committed and admitted to.”

At the same time as officers are failing to humanely work with homeless people, park managers are facing struggles of their own with unhoused communities.

In Colorado, forest rangers say unhoused communities on forest lands have left behind dangerous illegal fire pits and litter, and have threatened officers. In 2015, a man living illegally in the Uncompahgre National Forest generated 8,500 pounds of garbage that required 48 volunteers and a helicopter to clear away. Illegal campers in the state caused a 600-acre wildfire, and similar cases have occurred in wild areas of Alaska and Northern Arizona.

Fires also threaten the unhoused people themselves, according to officials. In Southern California’s mountainous San Bernardino County, social service teams conduct outreach to unhoused people living in areas of high wildfire danger during fire season – though local officials have also adopted resolutions ratcheting up their powers to clear encampments summarily.

Encounters between law enforcement and the homeless are clearly here to stay, according to US Forest Service research social scientist Lee Cerveny. The topic hasn’t been the subject of widespread research, but early indications suggest the phenomenon is increasing.

Her team has surveyed Forest Service rangers around the country, and almost half said they were seeing an increase in encounters with non-recreational campers. The most intense concentration of encounters, she told The Independent, were in Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.

States across the Mountain West, where housing costs are high and services may be concentrated most in big cities, are struggling.

The population rangers encountered, however, has been found across the country, and is surprisingly diverse, ranging from seasonal outdoor workers near expensive ski towns, to veterans, to “sovereign citizens” seeking to live off the grid.

“What was most surprising to me, one of the more surprising findings, was a group that seems to be widely recognised as a prominent group of people living on the forest are seniors, retirees who are housing insecure or who some might be living in a recreational vehicle or other kinds of trailers and things, especially in the Southwest and Pacific Coast,” she said.

The book and later film Nomadland highlighted the increasing proportion of seniors living on the continuum of homelessness, traveling across the country in RVs, sometimes surviving on seasonal work at places like Amazon and Walmart.

Studying these populations is difficult enough, and serving them can be even more challenging. Like the Roberts family, many of those living on federal lands move from place to place, meaning they may pass from the jurisdiction of the federal government, to a city, to a state park in a matter of days, well before the bureaucracy of housing services in the US can get them help.

“It is complicated,” the Forest Service researcher said. “It’s challenging for an agency like the Forest Service. Most people who work there are trained to manage the landscape and may not necessarily have training in this area in addressing homelessness and houselessness. Protecting the rivers, protecting the lands, protecting wildlife and recreation benefits and opportunities is what they’ve been trained to do, and now if there are people who are struggling and living in the forest, how does that fit into the picture? That’s something people are talking about.”

The Forest Service told The Independent, “We do not have a way to track the number of unhoused people on National Forest land.”

“Since we don’t track this information, we don’t know if the proportion of unhoused people on Forest Service land has been increasing in recent years,” it added.

Bevin Carithers, ranger supervisor at Boulder County Parks and Open Space, told The Independent his department encounters a few unhoused people a month on county lands. Because these parcels are in slightly more remote areas compared to the bustling city of Boulder, he said the slower pace affords county officials the chance to slowly get to know homeless people and assess their needs, usually sending a multi-department team that can include social service providers and sheriff’s deputies.

“Everyone has a different circumstance,” he said. “Either they’ve been laid off from work, or they don’t have a place to stay, or they have suffered from some kind of mental illness. Our ability to take our time to react to these situations gives us that opportunity to really dig deep.”

“We do not rush the situation,” he added. “We’ll take as much time as we need to deal with the individual. Sometimes it ends up costing us more money in the clean-up, but in the end we’re solving the situation.”

This measured approach, favouring social services over defaulting to police tactics, is one that’s supported by groups like the American Medical Association and the American Public Health Association, and, at least on paper, the Biden administration. However, it is at odds with the prevailing national climate on homeless.

Dozens of leaders, hailing from liberal and conservative states alike, are currently asking the Supreme Court to overturn an appeals court’s ban on issuing citations for illegal camping when municipalities don’t have available shelter space.

Even in comparatively progressive states like California, major cities like San Francisco and Sacramento are locked in bitter lawsuits, where officials are pushing for the ability to clear homeless encampments despite their shelter systems often lacking enough accessible beds to house everyone living on the streets on a given night. The state has spent $17.5bn trying to combat homelessness over the last four years, but advocates argue police are diverting some of these funds into their own coffers.

Mr Tars of the NHLC said a recent Los Angeles budget featured $87m of the $100m allocated to homelessness programmes going to law enforcement, jail, and policing costs.

Housing advocates hope officials change course and adopt anti-homelessness initiatives focused on public health and housing over law enforcement.

For some, like Brooks Roberts, that shift would have drastically altered the course of his life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments