Biden says burn pits killed his son. More than 261,000 vets are sick. So why isn’t the US doing anything?

Vast open-air pits where trash burned around the clock were simply part of life on deployment for troops in America’s post-9/11 wars. Now, thousands are sick and dying because of the toxic exposure and feel abandoned by the country that they fought for, writes Rachel Sharp

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While stationed in Baghdad, soldiers nicknamed it “the Iraqi crud”.

For many, over-the-counter medication helped ease their breathing difficulties while on tour before they recovered on their return to the US.

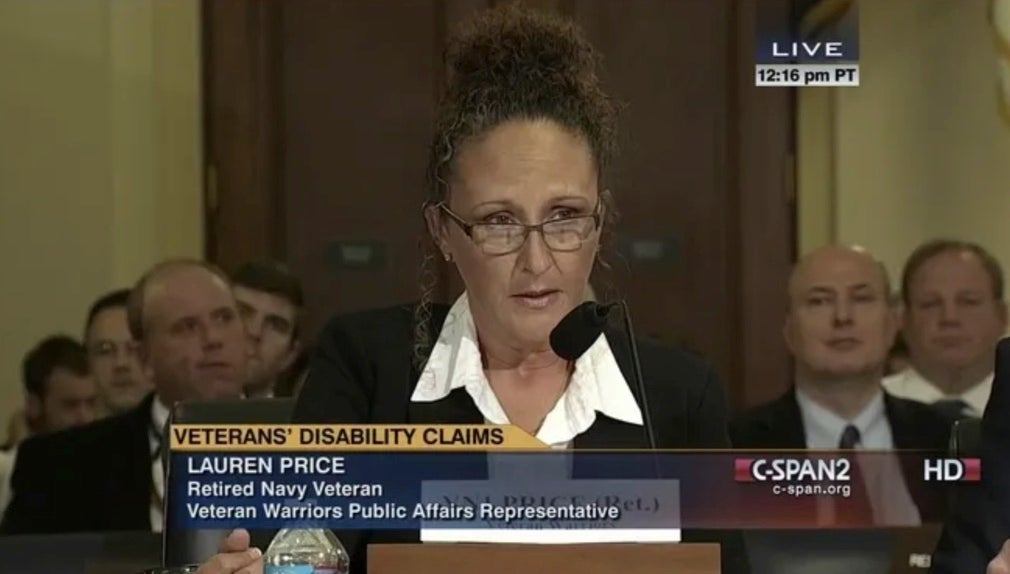

But for Lauren Price, the crud never went away.

Within a few short months of returning from her 13-month deployment to Iraq in 2008, she could no longer manage the three-mile jogs she used to run every day.

In 2011, she was diagnosed with terminal constrictive bronchiolitis – a rare form of lung cancer caused by breathing in toxins – and she was medically retired from the Navy two years later.

Within a few short years she couldn’t even walk to her mailbox without losing her breath and needing to take a break.

Her lung capacity fell to around 30 per cent, functioning at less than a third of that of a typically healthy person.

On 30 March 2021, Lauren passed away from complications related to cancer. She was 56.

“It was really hard to see her deterioration but it was so much harder for her as she had always been so independent,” Lauren’s husband Jim Price tells The Independent.

“She was a single mother for many years and so it was difficult for her to acknowledge that she needed help or couldn’t do as much as she used to.”

Long before her death, Lauren knew that her health issues were directly related to her service for her country, after facing prolonged exposure to burn pits during her tour of Iraq.

She had testified before Congress how she was particularly exposed to the toxic fumes as she became a lead convoy driver and drove trucks laden with vehicle parts to and from the pits.

Leave nothing behind

During America’s post-September 11 wars, huge open-air burn pits were used to dispose of the mountains of trash on US military bases.

Everything from food packaging to human waste to military equipment, chemicals, paints, petrol, plastics and tyres were dumped into the huge pits and set alight with jet fuel.

Many of the pits covered acres of land and burned all year round without going out, all within close proximity to where US troops were sleeping, eating and working.

One of the biggest pits spanned 10 acres, burning around the clock at Balad Air Base, just north of Baghdad.

It’s a waste disposal practice that was banned on US soil back in the 1970s because of the health risks from the release of toxic fumes but which, five decades later, is still practiced by the US army on deployment to foreign countries, leaving American servicemen and women exposed to these toxins every single day.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, it was simply common practice as troops were required to leave nothing behind.

“Everything had to be burned everywhere we went – we couldn’t just leave trash behind and it was also a security risk,” explains Tom Porter, executive vice president of government affairs at Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) and a Navy veteran of Afghanistan.

Mr Porter tells The Independent that there are other pollutants on the bases, but people typically refer to everything altogether as burn pits.

“Wherever Nato forces were in Afghanistan, facilities were powered with diesel generators that would be three metres tall and wide and they were just pumping out black smoke that you breathed in all of the time,” he says.

“And probably even worse than that was the portable toilets on the bases as there was no sewage works so you would take out the waste and pour jet fuel on it. That happened every day where Nato forces were.”

On one large base in Kandahar in southern Afghanistan a vast lake of raw sewage earned the nickname the “Poo Pond”, as the waste from portable toilets used by 30,000-plus troops was dumped into one gigantic cesspit.

Low on the radar

Mr Price, who was on tour in Iraq with his future wife, says that the burn pits were just part and parcel of their life on deployment.

“Everybody saw them and noticed them, it was kind of just a fact of life,” he says.

“We were in third-world country locations and you have to dispose of waste so it was just something that needed to be done.

“At the peak of the surge there were 250,000 military members and civilian contractors there so if you just think about everyday waste from each of these people drinking four or five one litre plastic bottles of water a day and getting three meals in Styrofoam containers - that’s not even accounting for things like the tyres that go bad and the equipment that breaks and so on.

“So it was something everyone recognised that there was really no other option for at the time.”

When you’re just trying to make it to the end of the day without being killed in warfare, the long-term impacts of breathing in these toxins doesn’t really register high up on anyone’s concerns, he says.

“Your concerns throughout the day are: one, not getting blown up; two, not getting shot; and three, can we get enough food and water,” he says.

“So it’s a different kind of mindset where it was so low on the radar.”

Even with today’s hindsight about the dangers of the burn pits, Mr Price says he doubts it would have made any difference to Lauren’s decision to serve her country.

Lauren had always wanted to join the Navy.

But these plans were put on hold when she became a military wife and had three sons.

Then, inspired to act following the September 11 terrorist attacks and with her children all grown up, the time was finally right in 2006.

It was during civil affairs training at Fort Bragg that she and Mr Price, who had served in the Navy since 1989, first met.

They were both deployed to Iraq at the same time and worked together in the legal team. They stayed in contact when they returned and “one thing led to another” and they married in 2011, says Mr Price.

Navigating the VA

Following his retirement and her medical discharge, they spent the last decade of Lauren’s life advocating for other veterans returning from war with life-changing conditions through their nonprofit Veteran Warriors.

They founded the organisation together when, with Lauren’s health worsening, they learned firsthand the “anxiety and stress” of trying to navigate the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) – the government agency whose purpose is to provide healthcare services and disability claims to military veterans – particularly for those with health conditions related to burn pits.

(The Department of Defense (DOD) meanwhile provides healthcare and determines the disability status of service members before they leave active duty.)

For Lauren, it was a three- to four-year process – which involved reaching out to her local lawmaker – before she was even given a disability rating by the VA.

Her husband says that the whole process to access healthcare through the VA was “more anxiety-causing and stressful” as the agency effectively refused her treatment by telling her they wouldn’t treat her constrictive bronchiolitis until her PTSD – an incurable illness – was “cured”.

In the end, she gave up and went down the civilian medical insurance route instead.

That option, says Mr Price, is something many veterans aren’t fortunate enough to have.

“Their only real choice is the VA and it can be a nightmare,” he says.

“People would assume it is a seamless transition from the military to the VA but it’s not.”

Burden of proof

Lauren is just one of thousands of US veterans who have developed health conditions including rare cancers, lung conditions, respiratory illnesses and toxic brain injuries after being exposed to burn pits on deployment overseas.

Almost 261,000 veterans have signed up to the VA’s Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry since its launch in 2014, registering that they are suffering from health conditions they believe to be caused by exposure to burn pits.

But the true number of those impacted is likely even greater, with the VA estimating that 3.5m servicemembers and veterans have been exposed to burn pits and airborne toxins.

And yet, the VA is turning down almost 80 per cent of claims for healthcare and disability related to toxic exposure.

In September 2020, a senior VA official testified before Congress that just 22 percent of disability claims mentioning burn pits had been approved between 2007 and 2020 - leaving veterans without healthcare or financial support for conditions believed to be directly caused by their service to their country.

One of the biggest hurdles for veterans is that the burden of proof is currently on them to prove a direct link between their exposure to burn pits and their illness.

Which is something that – even after introducing the burn pit registry in 2014 - the VA has long insisted there is not enough evidence to prove.

Research that did appear to prove a link came to an abrupt end.

In 2004, Dr Robert Miller from Vanderbilt University began one of the first studies into the links between burn pits and illnesses when several seemingly fit soldiers were sent to him from Fort Campbell after failing fitness tests and presenting unexplained respiratory issues on their return from Iraq.

After performing lung biopsies, he found that dozens were suffering from constrictive bronchiolitis which didn’t show up on regular exams such as X-rays and pulmonary function tests. The military then stopped sending soldiers to see him.

Then, in 2012, former VA epidemiologist Steven Coughlin testified before Congress that VA officials were manipulating or hiding data that supported veterans’ claims of illnesses related to burn pits.

Even now in 2022, a statement on the VA website still reads: “At this time, research does not show evidence of long-term health problems from exposure to burn pits.”

“If you’re in the military and you get shot then there’s a bullet and a wound - it’s pretty cut and dry that the injury was caused by your service,” says Mr Price.

“But if you’re exposed to toxic chemicals and then you come home and have a severe illness the direct connection is not as easy to prove.

“It’s pretty obvious – but there is no definitive way to say 1,000 per cent that the condition Lauren had in her lungs was caused by her exposure to the burn pits in Iraq.”

Also complicating this burden of proof is that the illnesses caused by toxic exposure can develop many years after the deployment.

Abandoned by the country that sent them to war

As a result, many veterans describe coming home from war and being abandoned by the same government that sent them there.

Le Roy Torres had transitioned from active duty to an Army reserve and was working as a Texas state trooper for the Texas Department of Public Safety (TDPS) when he was deployed to Iraq in 2007.

He began suffering respiratory issues while on deployment and was hospitalised within a matter of weeks of returning home to the US at the end of his tour.

He was medically discharged from the Army but doctors were at a loss as to what was wrong with him.

“He sounded like he was coughing up a lung,” Rosie Torres, Le Roy’s wife and cofounder of Burn Pits 360, tells The Independent.

They were making countless trips to the hospital and, at one point, he collapsed at home in front of their three children.

“We would come back from the hospital and turn to the VA and they’d say ‘sorry, there’s nothing we can do’,” says Ms Torres.

He was finally diagnosed after Ms Torres began “googling soldiers coming back from Iraq and dying” and found a whole online community of widows, widowers or families whose loved ones had returned from war and were sick or dying from burn pits exposure.

After more research, they tracked down Dr Miller who diagnosed Le Roy with constrictive bronchiolitis.

For a long time, the VA denied Le Roy’s claims for service-connected illness due to burn pits exposure because constrictive bronchiolitis is not a presumptive condition.

Even now, he only gets 30 per cent of available benefits for a service-connected illness.

When asked why, Ms Torres simply says: “Because it’s the VA.”

Ms Torres actually worked for the VA at the time that her husband came back from the war ill.

She experienced life as an employee inside the VA by day and would then go home and experience life as a veteran’s wife fighting the VA to get the support her sick husband was owed.

She says that no one inside the agency was even talking about the issue of burn pits during her 23 years of working there.

“It was non-existent in the VA, no one spoke about it at all. There were no documents on it, no training on it, nothing at all,” she says.

“Working for the VA I saw the bureaucracy and red tape and systemic barriers that are in place and began to realise ‘wow this is really happening to people and no one really cares’.”

She adds: “The VA has a horrible misconception that these people are malingerers, that they’re defrauding the government.

“It’s like if only they knew what we would give to have our old lives back!”

To make matters worse, Le Roy wanted to return to work for the TDPS but asked to be reassigned to a different role due to his condition.

The TDPS refused and he was forced to resign, says Ms Torres.

Le Roy sued for discrimination under a law which makes it illegal for employers to discriminate against employees over military service but lost in state court.

In December, the US Supreme Court agreed to hear Le Roy’s case this spring.

With Le Roy losing his job and the VA not paying up at the time, Ms Torres says their family was forced to use up all of their life savings just to keep a roof over their heads.

She also had to take early retirement.

“In order for us not to get the house foreclosed I had to take early retirement and withdraw all our money from our savings,” she says.

“My family was like ‘why are you doing this? You shouldn’t do that’ and I was like ‘if I don’t we’ll lose our house’. We didn’t have a choice. We didn’t have a plan b and c.

“This is war and it’s a war that has followed us home.”

Le Roy had served his country for a total of 23 years.

‘A war that followed us home’

The couple turned their online community into Burn Pits 360, a grassroots organisation that lobbies the US government for change and advocates for veterans exposed to burn pits.

The nonprofit established an independent burn pits registry back in 2010 – four years before the VA set up its own.

“There has been no accountability all the way across it so we all just have to pick up the scraps of money left after wiping our life savings, drag our butts to Washington and create a website to try to get the government to do its job,” says Ms Torres.

As Mr Porter explains, members of the military accept their service comes with a risk to their lives.

What they do not accept is that, when their health suffers or a loved one dies, the government that sent them to war abandons them on their return.

“People understand that they are coming into contact with dangerous things in war but you presume the government will take care of you when you come back,” he says.

“If we get to the point where we have such widespread health impacts from pollutants but the government says ‘well the science doesn’t really prove that your pancreatic cancer was caused by a burn pit’ then people will think twice about joining the military and that will be a problem.

“We need to make sure service members know that when they join service, yes it is a dangerous job but we’re going to take care of you if something happens to you.”

It’s an issue that many hoped President Joe Biden would make a priority after entering the White House – especially in light of his personal ties to the issue.

Beau Biden

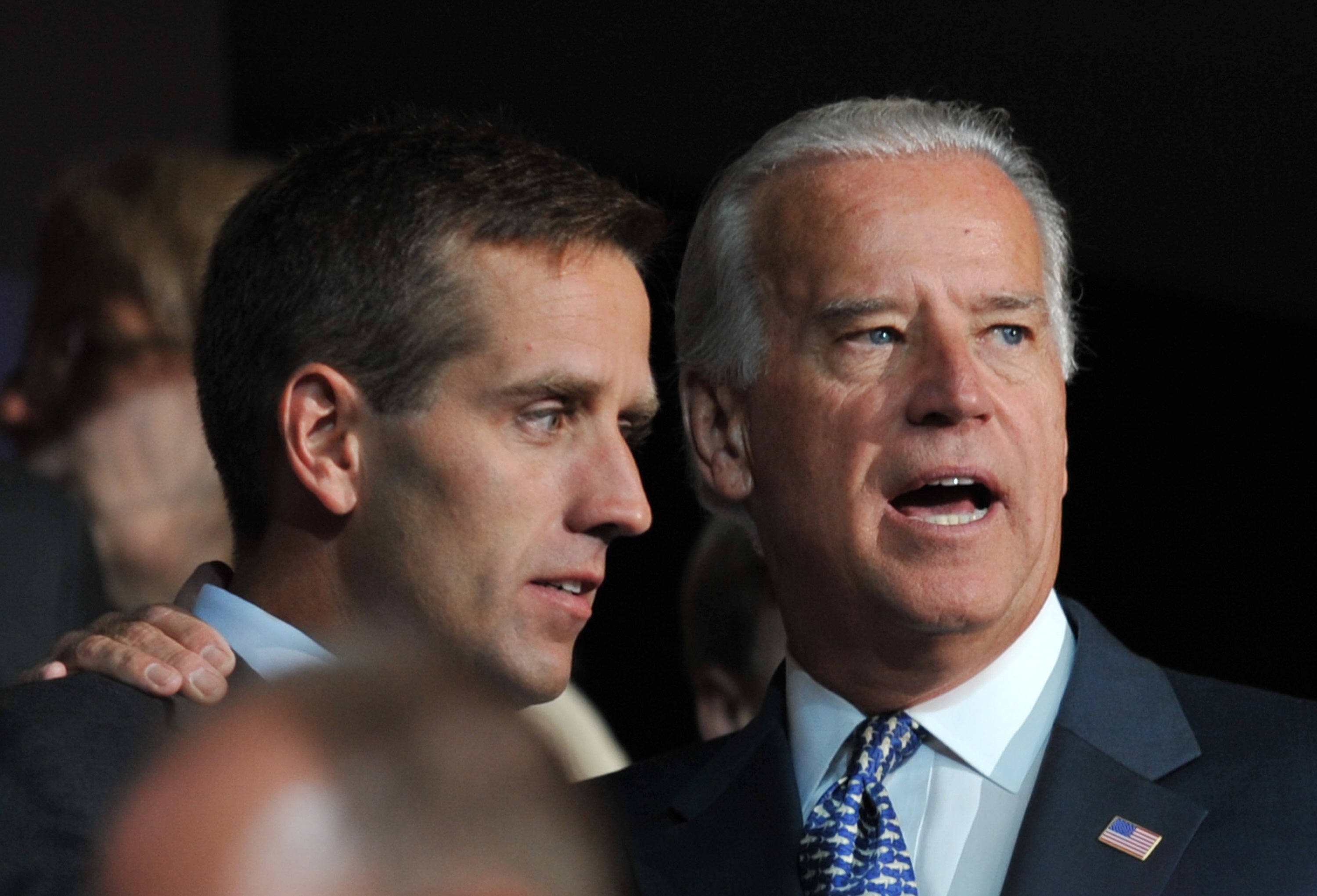

The president has said publicly that he believes the cancer that killed his son Beau was linked to his exposure to burn pits.

Beau Biden was a captain in the Delaware Army National Guard and was deployed to Iraq in 2008, spending much of the next year breathing in the 10-acre burn pit at Balad Air Force Base.

Two years later, he began suffering severe health conditions. First, he suffered a stroke in 2010 before he was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, in 2013.

He died in 2015 at the age of 46.

In a 2018 interview, Mr Biden said he had been “stunned” to learn that there was a whole chapter about his son in Joseph Hickman’s book The Burn Pits: The Poisoning of America’s Soldiers and said that it had opened his eyes to the potential link between Beau’s service and his premature death.

By 2019, during a speech to the Service Employees International Union, Mr Biden appeared to have made up his mind that Beau’s death was indeed linked to the burn pits he was exposed to in Iraq.

“He spent a year in Iraq and came back decorated, conspicuous service medal honor, bronze star in war zone, etcetera,” he said.

“And because of exposure to burn pits, in my view, I can’t prove it yet, he came back with stage 4 glioblastoma.”

He added: “Eighteen months he lived, knowing he was going to die.”

President Biden’s personal ties present a major opportunity for the issue to finally be taken seriously in Washington, believes Mr Porter.

“He has a personal connection because he believes his son may have died from burn pits exposure,” he says.

“And the president’s personal priorities become the priorities of the administration which become the priorities of the VA so it’s important that he is behind the issue.”

A ‘seismic shift’ in administrations

Since he took office, the Biden administration has taken a number of steps to make it easier for veterans exposed to burn pits to access federal benefits and healthcare.

For the very first time, some health conditions are now presumed to have been caused by exposure to burn pits.

Three conditions – asthma, rhinitis and sinusitis – were first listed in August as presumptively linked to toxic exposure.

This means that the VA now presumes that veterans diagnosed with one of these conditions within 10 years of returning from deployment to certain countries are suffering these illnesses because of toxic exposure during their service.

These veterans are therefore eligible for disability benefits.

On Veterans Day in November, the president also announced the launch of a probe to investigate whether some rare respiratory cancers, lung cancers and constrictive bronchiolitis - the condition Lauren and Le Roy were diagnosed with - are also tied to burn pits.

He gave the VA 90 days to provide recommendations about adding these as presumptive illnesses.

Glioblastoma – the rare brain cancer Beau died from – was not on the list.

In Mr Biden’s speech, he vowed that “anybody who was anywhere near those burn pits, that’s all they have to show and they get covered, they get all their health care covered”.

In late December, Mr Biden then signed two bills into law as part of the $768 billion National Defense Authorization Act for 2022 , expanding the burn pit registry and enhancing medical training for healthcare providers on the effects of toxic exposure.

The pair of bills was put forward by Rep Raul Ruiz, a former doctor and founder of the Congressional Burn Pits Caucus who has pushed for years for Congress to act over the military’s use of burn pits.

Rep Ruiz tells The Independent that he has seen a “seismic shift” in attitudes towards the issue from both the VA and the White House since Mr Biden took office.

“Before the Biden-Harris administration, every time we would hold a hearing with the VA and others in the previous administration, there were always excuses,” he says.

“They would say that ‘there’s no evidence to show the link between burn pits and other cancers and illnesses’ and that would infuriate me as they knew quite well that there was enough evidence through case studies, through dirt sampling, through lung biopsies as well as through parallel studies done in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

“This is a serious issue as these veterans have survived the battlefield only to come home and be casualties of war.”

The congressman says that “for the first time ever” an administration now recognises the link between the burn pits and the conditions veterans are suffering from, shifting the conversation from complete denial of any link to what must be done about it.

“For the first time ever an administration is now recognising that there is a relationship between inhaling carcinogens and cancers and respiratory illnesses,” he says.

“Now the debate is not if burn pits harmed service members, it is which illnesses they caused and so which should be presumptive.

“So there has been a seismic shift in the way the VA and the administration are dealing with burn pits.

“For the VA to now recognise that asthma is a presumptive illness caused by exposure to burn pits is unheard of.”

‘Political breadcrumbs’

Mr Biden’s speech on Veterans Day did send a “definite signal to his administration that this is a priority”, agrees Mr Porter.

He also believes that VA Secretary Denis McDonough - who was sworn in in February 2021 - understands it’s an issue that the agency needs to tackle.

But, while things appear to be “moving in the right direction”, for veterans who have been fighting this for years, things aren’t moving quickly enough.

“These aren’t just some random illnesses that no one sees. Friends, family, people we know personally are dying,” says Mr Porter.

“This is something that veterans are living and breathing and dying from so it is offensive to us when this process is drawn out for years because many people don’t have years.”

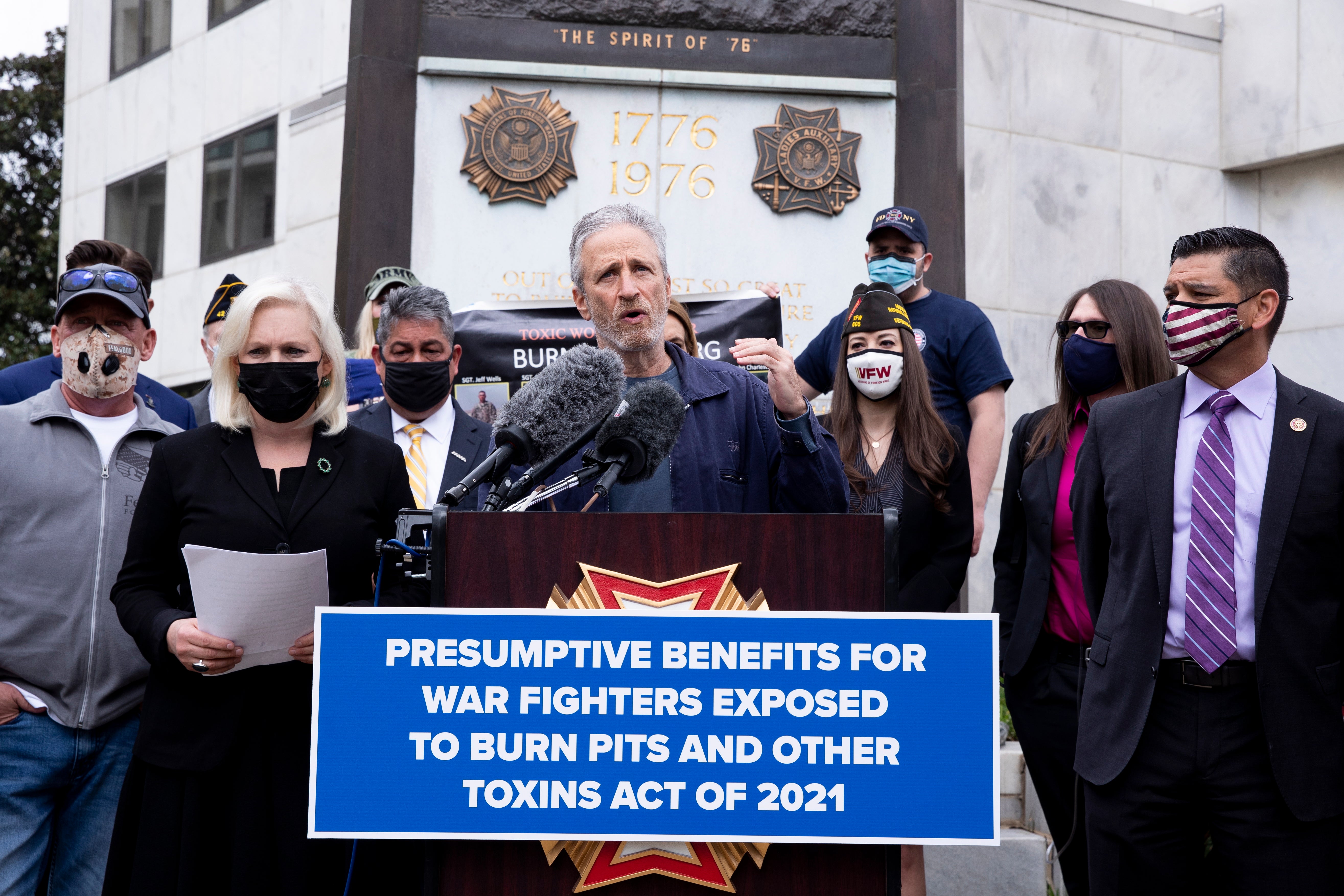

John Feal tells The Independent that the steps taken so far by the Biden administration are nothing more than “political breadcrumbs”.

Mr Feal is a 9/11 survivor who advocated for first responders to get access to healthcare for illnesses and injuries sustained at Ground Zero.

Much like the veterans exposed to burn pits overseas, 9/11 rescue workers are still developing cancers and respiratory illnesses years on from the terrorist attacks, after breathing in the toxins from the burning jet fuel while spending months and months combing through the rubble in New York.

Mr Feal successfully pushed Congress to pass a bill to ensure the government provides permanent compensation to these rescue workers.

More recently, he has become an advocate for veterans suffering from illnesses caused by toxic exposure to burn pits alongside TV host Jon Stewart.

He says the addition of three respiratory illnesses to the presumptive list of conditions connected to burn pits is nothing more than “a smoke and mirrors show” while a whole range of other cancers and illnesses are not yet even on the table.

“That’s just political breadcrumbs, a smoke and mirrors show,” he says.

“It’s just throwing a couple of things out there so that on the surface it looks like they’re doing the right thing.

“And they don’t need 90 days any more [to present a link to certain cancers]... that was weak and poor leadership from the president,” he adds of the Veterans Day announcement.

A VA spokesperson tells The Independent that making the three respiratory conditions presumptive is just “a first step of more to come as we tackle the difficult topic of environmental exposure” and that addressing the health effects associated with toxic exposure is “a major priority” to the president and his administration.

“The president believes we have one truly, sacred obligation – to properly train and equip our troops when we send them into harm’s way, and to care for them and their families when they return home,” he says.

He adds: “The Bidens are a military family, they know first-hand the sacrifices that our military families, caregivers, and survivors have made in serving our nation.”

Secretary McDonough has also vowed to “fight like hell on the issue”, he says, adding that the VA does however “understand” the frustrations among the veteran community.

“We understand the frustration some veterans are experiencing while we are working, but we are working hard to find the answers for veterans that are scientifically sound and legally defensible,” says the spokesperson.

A war on burn pits

Mr Feal says he believes Mr Biden does indeed care about the issue but his personal connection to burn pits could be “holding him back”.

“We’re disappointed by the lack of action from the White House,” he says.

“I know him and he’s a good man but I think Biden just doesn’t want to make his son’s death political and so - while I’m confident he will sign any bill on this into law - I think he is holding back.”

What the president should actually be doing is declaring a “war on burn pits”, he says.

“We just ended a 20-year war. Now, all he has to do is start a new war on ensuring these people get the healthcare they deserve,” he says.

“We need to start a war on burn pits and make sure this situation doesn’t happen again.”

Of course, the US has already been in this situation before.

Troops returning home from the Vietnam War began experiencing illnesses caused by toxic exposure to Agent Orange - a herbicide used by the US military to clear the heavy jungle.

For years, these veterans fought for their conditions to be recognised as connected to their service before the Agent Orange Act was finally passed in 1991 – 16 years after the war ended.

Now, advocates are urging Congress to pass legislation that will presumptively link several conditions and illnesses to toxic exposure, taking the burden of proof away from veterans.

Two similar bills were introduced in 2021 – The Comprehensive and Overdue Support for Troops of War Act or COST of War Act in the Senate and the Honoring Our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act or PACT Act in the House.

It’s anticipated that the House bill will be easier to pass due to the Democrat majority.

Mr Feal and Mr Stewart have met with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi several times, urging her to take the PACT Act to the House floor.

Following the latest meeting this January, Speaker Pelosi gave a press conference where she said “we have to have legislation passed” to support veterans affected by burn pits.

“It will be expensive but it is the price we must pay,” she said. “And from our standpoint, if you were there - you qualify.”

The PACT Act is sweeping legislation that includes several different bills to make it easier for veterans suffering illnesses related to toxic exposure to access VA disability benefits.

The biggest change would see 23 conditions being presumptively linked to toxic exposure, removing the burden for veterans to prove a direct link to service.

If it passes into law, it would grant eligibility to VA healthcare for thousands of veterans now suffering from cancers, respiratory issues and other illnesses after breathing in the toxic fumes from burn pits.

While resigned to the fact that it’s likely some parts of the bill will be dropped along the way, Mr Feal lists some non-negotiables: that it’s presumptive, that it’s “as big as possible”, and that the list of illnesses and countries stay put.

“We want a presumptive bill that is going to encompass all those affected by toxic exposure from burn pits,” he says.

“Veterans coming home from war sick from burn pits shouldn’t have to be their own advocate, lawyer and doctor.

“Everybody in America is guilty of saying ‘thank you for your service’ to our veterans but that’s all we do.

“We then stop short. It should be ‘thank you for your service and what can we do to help?’

He adds: “The true cost of war is taking care of men and women when they come home.”

True cost of war

It’s a cost that many on Capitol Hill don’t want to pay for, says Mr Porter.

However, service-related illnesses are part of the cost of war – a cost that veterans are already paying for with their health and shouldn’t have to pay for financially, he says.

“Some people in Congress say they don’t know how we can pay for this but this is part of the war that the same people decided to send us to.

“This entire problem is part of going to war, it’s part of the cost of war,” he says.

“We’re here to say that Congress is the one that sent us to war over the last 20 years so if they didn’t want to pay for the veterans injured from the war then they shouldn’t have sent us there in the first place.”

Mr Porter likens it to eating a meal in a restaurant and then refusing to pay.

“You go out for a nice dinner and eat it all then say ‘I hated my food, I don’t want to pay for it’,” he says.

“This is what I say to Congress: this is a meal you have already eaten and so you’ve got to pay for it.

“It’s the cost of the war you’ve already bought, you just need to take your money from your pocket and pay the bill.”

Mr Porter says that there is also a common misunderstanding among lawmakers now waking up to the issue: that veterans want to end the practice of burn pits altogether.

While that would of course be an ideal outcome, he explains that soldiers and veterans accept that burn pits are sometimes the only option in war.

“The discussion on Capitol Hill by people who don’t understand the issue is that we need to ban burn pits,” he says.

“We’re not looking to do that as we are going to go to war again so we are going to need to burn things again.

“Yes we want safer ways to burn things but it’s not practical to set up a recycling plant down the road from a base. We get that.”

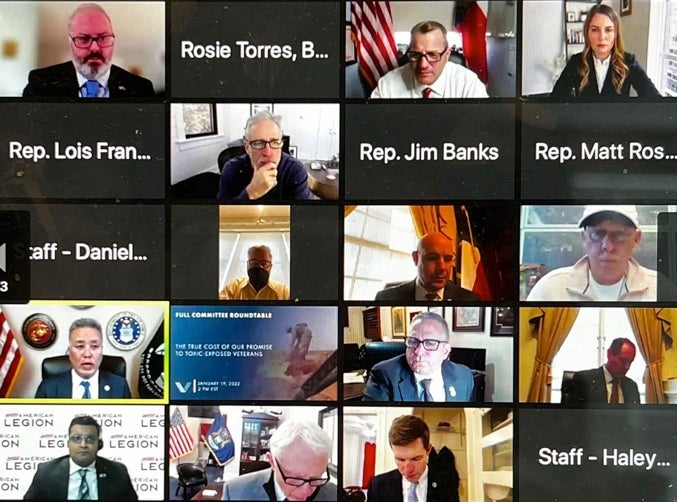

Perhaps one of the clearest signs of an unwillingness from some lawmakers to listen to the veteran community and take the issue seriously came during a recent House Veterans’ Affairs Committee virtual roundtable in January.

While veterans, veteran services organisations and advocates - including Ms Torres, Mr Feal, Mr Stewart and Rep. Ruiz - discussed how burn pits exposure is killing veterans and the importance of passing the PACT Act, Rep. Madison Cawthorn was caught on camera spending several minutes busying himself by cleaning his gun.

Ms Torres branded his behaviour “very disrespectful” and an “insult” to all US veterans who are sick and dying after serving their country.

“He does not belong on the committee. He clearly has no concept of how many of his constituents are sick and dying from the toxic wounds of war as if he did he wouldn’t be cleaning his gun right then,” she says.

“It was an insult to the American warriors, to the survivors and to the widows of soldiers who have died.”

Supporting veterans isn’t a partisan issue, says Mr Feal, warning that he isn’t afraid of (figuratively) “beating up” anyone who gets in the way of passing legislation.

“I don’t care if they’re Republican or Democrat I will punch them in the mouth - figuratively not literally - if they get in the way,” he says.

“I have zero tolerance for people who have power and don’t use it right.

“And no one wants to be that guy that says no to supporting veterans.”

Mr Feal is confident that the bill will pass in 2022.

But, after spending more than a decade trying to get the US government to provide her veteran husband with the healthcare he needs, Ms Torres is less optimistic.

“We’re hearing that the Senate is not in line with it being presumptive,” she says.

“There’s talk about why don’t we expand healthcare and then make presumptions later? But why would we do it later?”

She worries that there is still a disconnect with Congress, the VA and the DOD “not talking to each other” all the while “no one is paying attention to veterans and active duty servicemembers”.

Meanwhile, Le Roy’s health continues to decline.

“He has all kinds of medical issues and every year there’s more and more doctors, more and more symptoms and more and more visits,” she says.

“He’s dealt with a lot, the poor thing - the suffering is non-stop.

“What can you say after he’s had 10 years of suffering and pain? He doesn’t fit the description now of who he was back then.”

For Mr Price, it’s almost one year since he lost his wife because of the burn pits she was exposed to in Baghdad.

He says he is trying to carry on Lauren’s work supporting other veterans in her memory but finds it difficult at times “as it was such a big part of Lauren’s Life and our life together”.

As well as adjusting to life without Lauren, Mr Price has also been left wondering about the impact the burn pits could have had on his own health.

“I was always within 100 yards of Lauren so what she was breathing in I was probably breathing in too,” he says.

“Lauren’s younger son and I have talked about this on several occasions as he was also serving in Iraq for a year right after we were.

“We’re always wondering: is tomorrow going to be the day that the burn pits catch up with us too?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments