New ‘asteroid’ identified last month is now believed to be junk from failed moon landing

What looks like an asteroid may just be an old rocket from a failed moon-landing mission more than 50 years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An “asteroid” spotted by a Hawaii telescope last month and added to the official tally of may in fact be space junk from a failed moon landing 54 years ago, scientists have concluded.

The object, known as “asteroid 2020 SO”, is heading towards our planet and will be captured by Earth’s gravity in mid-November.

It will spend about four months circling Earth, experts believe, before shooting back out into its own orbit around the sun next March.

But Nasa’s leading asteroid expert has said he now believes it it not an asteroid. He believes it is part of a rocket.

“I’m pretty jazzed about this,” Paul Chodas told The Associated Press.

“It’s been a hobby of mine to find one of these and draw such a link, and I’ve been doing it for decades now.”

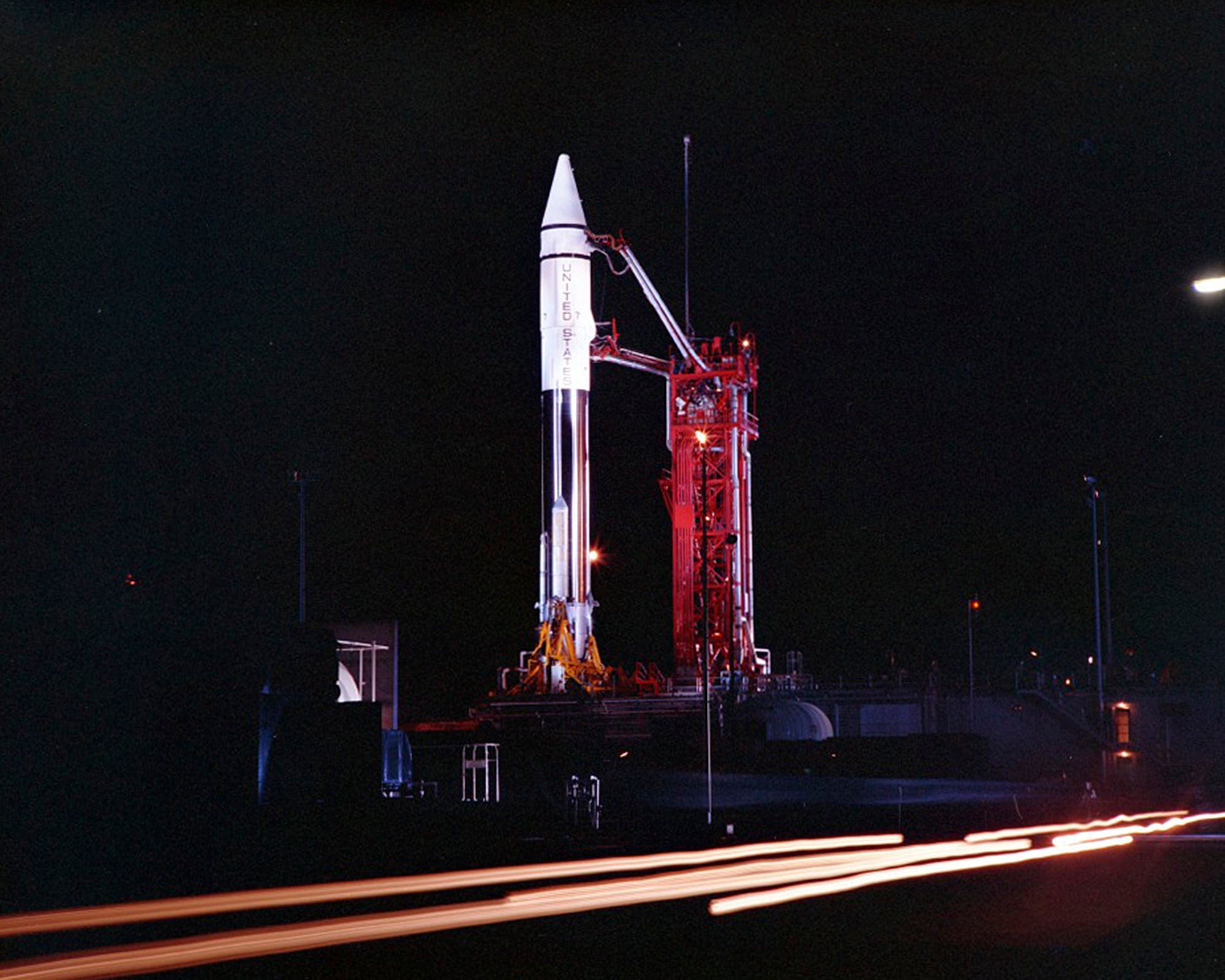

Chodas speculates that the object is actually the Centaur upper rocket stage that successfully propelled Nasa’s Surveyor 2 lander to the moon in 1966 before it was discarded.

The lander ended up crashing into the moon after one of its thrusters failed to ignite on the way there.

The rocket, meanwhile, swept past the moon and into orbit around the sun as intended junk, never to be seen again — until perhaps now.

Last month scientists in Hawaii came across the unexpected object while doing a search intended to protect our planet from doomsday rocks.

It was added to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center’s tally of asteroids and comets found in our solar system - just 5,000 shy of the 1 million mark.

The object is estimated to be roughly 26 feet, based on its brightness - making it around the size of the old Centaur, which is less than 32 feet long including its engine nozzle and 10 feet in diameter.

What caught Chodas’ attention is that its near-circular orbit around the sun is quite similar to Earth’s — unusual for an asteroid.

“Flag number one," said Chodas, who is director of the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

The object is also in the same plane as Earth, not tilted above or below - another red flag. Asteroids usually zip by at odd angles.

Lastly, it’s approaching Earth at 1,500 mph, which is deemed slow by asteroid standards.

As the object gets closer, astronomers should be able to better chart its orbit and determine how much it’s pushed around by the radiation and thermal effects of sunlight. If it’s an old Centaur — essentially a light empty can — it will move differently than a heavy space rock less susceptible to outside forces.

That is how astronomers normally differentiate between asteroids and space junk like abandoned rocket parts, since both appear merely as moving dots in the sky. There likely are dozens of fake asteroids out there, but their motions are too imprecise or jumbled to confirm their artificial identity, said Chodas.

Sometimes it’s the other way around.

A mystery object in 1991, for example, was determined by Chodas and others to be a regular asteroid rather than debris, even though its orbit around the sun resembled Earth’s.

Even more exciting, Chodas in 2002 found what he believes was the leftover Saturn V third stage from 1969′s Apollo 12, the second moon landing by NASA astronauts. He acknowledges the evidence was circumstantial, given the object’s chaotic one-year orbit around Earth. It never was designated as an asteroid, and left Earth's orbit in 2003.

The latest object’s route is direct and much more stable, bolstering his theory.

“I could be wrong on this. I don’t want to appear overly confident,” Chodas said. “But it’s the first time, in my view, that all the pieces fit together with an actual known launch."

And he's happy to note that it's a mission that he followed in 1966, as a teenager in Canada.

Asteroid hunter Carrie Nugent, of Olin College of Engineering in Needham, Massachusetts, said Chodas’ conclusion is “a good one” based on solid evidence.

“Some more data would be useful so we can know for sure,” she said in an email. “Asteroid hunters from around the world will continue to watch this object to get that data. I’m excited to see how this develops!”

The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics' Jonathan McDowell noted there have been “many, many embarrassing incidents of objects in deep orbit ... getting provisional asteroid designations for a few days before it was realized they were artificial.”

It's seldom clear-cut.

Last year, a British amateur astronomer, Nick Howes, announced that an asteroid in solar orbit was likely the abandoned lunar module from Nasa's Apollo 10, a rehearsal for the Apollo 11 moon landing.

While this object is likely artificial, Chodas and others are skeptical of the connection.

Chodas' latest target of interest was passed by Earth in their respective laps around the sun in 1984 and 2002.

He predicts the object will spend about four months circling Earth once it’s captured in mid-November, before shooting back out into its own orbit around the sun next March.

But it was too dim to see from 5 million miles away, he said.

Chodas doubts the object will slam into Earth — “at least not this time around.”