American sisters’ assisted suicide in Switzerland spurs calls for more US states to adopt aid-in-dying laws

The deaths of two Arizona sisters in Europe stunned colleagues and family. But as end of life legislation makes slow progress in more than a dozen US states, seeking assisted dying overseas is often the only option, writes Bevan Hurley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At Pegasos, a voluntary assisted dying association in Basel, Switzerland, death costs 10,000 euros, or just over$11,000.

The figure includes paperwork and consultations, a prescription for the sodium barbiturate Nembutal, an appointment where the drugs are administered, cremation and couriering of the patient’s ashes home.

The deed is performed in a windowless “cocoon room” with soft lighting and comfortable sofas. Patients can choose whether to receive a lethal dose through an arm-fed tube which they control, or by drinking the lethal solution, along with an anti-vomiting drug.

When the time comes, the patient can play their favourite song while holding the hand of a loved one. If the drug is taken intravenously, they slip off almost immediately and die shortly afterwards.

Doctors will then usually notify Swiss authorities, who attend the clinic afterwards to ensure everything was carried out “within the legal framework”.

Sisters Lia Ammouri, 54, and Susan Frazier, 4 – high-achieving, popular and seemingly healthy, happy medical professionals – travelled to Basel from their home in Arizona via Chicago on 3 February.

Ms Ammouri, a palliative doctor, had dedicated much of her professional life to caring for people at the end of theirs.

And Ms Frazier, a nurse, had recently been promoted to a senior leadership position at Aetna Health Insurance where they both worked. One colleague recalled her blasting The Final Countdown by Europe every Friday, so excited she was to reach the weekend.

The sisters’ laughter-filled stories always revolved around each other, friends recalled. Ms Frazier, who had a high-pressure job looking after acutely ill patients, was able to “laugh the stress away”.

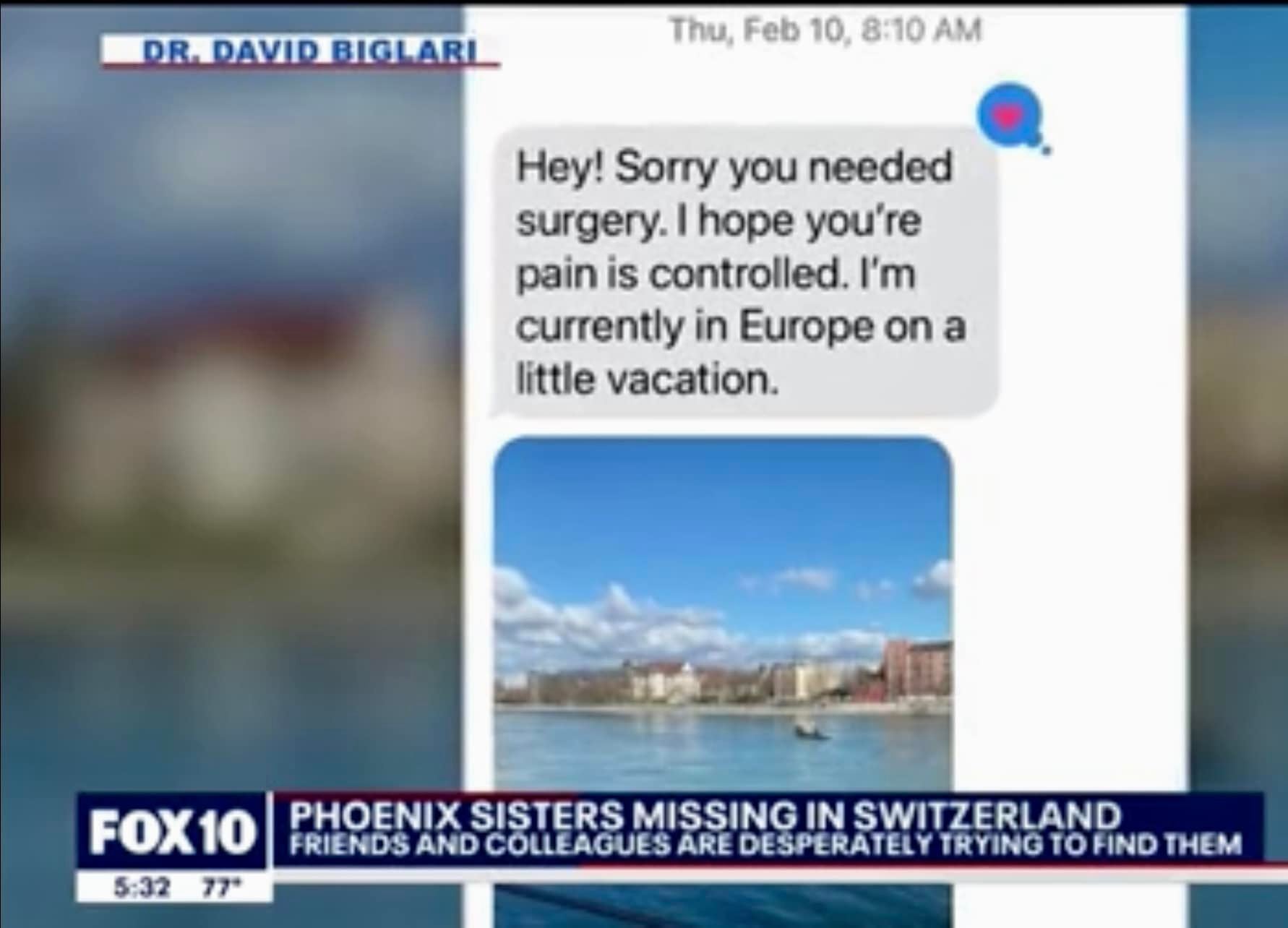

They didn’t tell any family or friends they were intending to end their ownlives, even booking return flights back to the US on 13 February and being expected back at work on 15 February.

Friends thought they might have been kidnapped, and that the spelling errors in their text messages was evidence that someone was impersonating them.

On Tuesday, a spokesman for the Basel-Landschaft public prosecutor’s office confirmed to The Independent that the sisters had died by suicide “within the legal framework”.

“The public prosecutor’s office of the Canton of Basel-Landschaft confirms that the two US women died during their stay in Switzerland. They both committed suicide at an assisted suicide organisation,” Michael Lutz told The Independent.

As tributes flowed to the women’s sense of humour and kindness, their brother Cal and friends were left with many unanswered questions.

“They were really special. They never hurt anybody,” Cal Ammouri told The Independent.

“I’m never going to get over it. I’m all alone now.”

Pegasos is one of several Swiss-based organisations which offer access to end-of-life medical assisted dying for thousands of foreigners, sometimes referred to as “suicide tourists”.

At the time of publication, Pegasos had not responded to several questions from The Independent about its end of life programme.

Swiss law tolerates medically assisted dying in certain situations, as long as the patient is over 18, able to administer the dose themselves, and is not being advised by someone trying to pressure them or take advantage of them.

Due to strict laws around assisting suicide in most US states, hundreds of so-called “suicide tourists” have travelled to Switzerland to die over the past two decades.

Only about one in five Americans live in states that have passed what advocates refer to as medical aid-in-dying legislation.

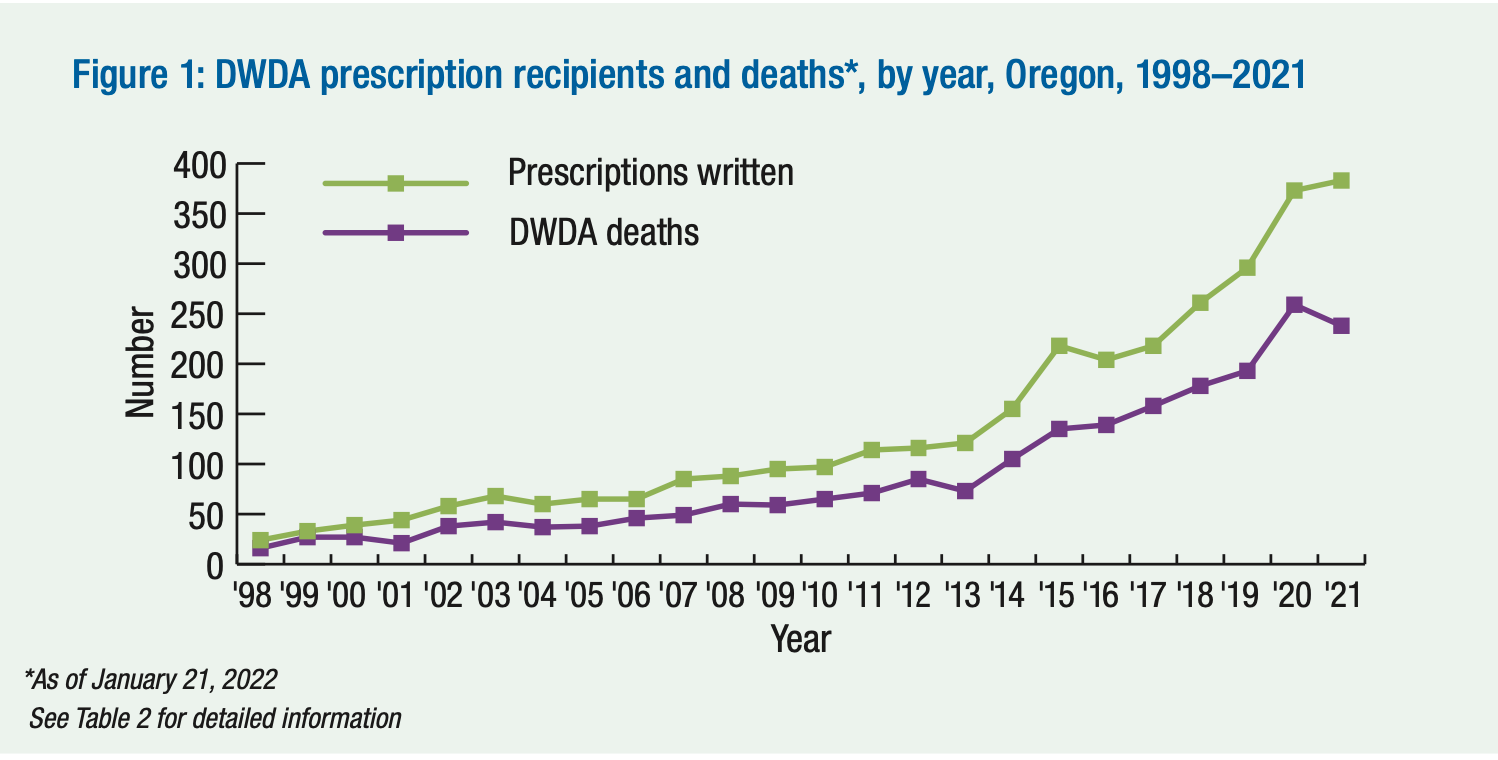

The Oregon Death with Dignity Act, which came into law in 1997, was the first in the country to offer the terminally-ill the right to self-administer lethal drugs prescribed by a doctor.

Since then eight other states have passed similar laws, including California, Colorado, Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine and New Mexico, while Montana allows assisted dying via a State Supreme Court ruling.

Twelve more states, including Ms Ammouri and Ms Frazier’s home state of Arizona, are currently considering bills.

Strict residency requirements make it difficult for terminally ill patients to receive medical aid if their state does not allow it.

Peg Sandeen, CEO of advocacy group Death with Dignity, told The Independent: “Every year, a few terminally ill individuals manage to move across state lines to a jurisdiction where Death with Dignity is legal. However, this option has proven difficult, both technically and physically, as moving when you are dying is a nearly impossible task.”

The lack of mobility from being severely ill makes it hard enough, but finding a doctor willing to prescribe life-ending drugs to a new patient can be a bigger obstacle.

Portland-based non-profit Compassion and Choices filed a lawsuit challenging Oregon’s residency requirement last October on behalf of physician Nicholas Gideonse, alleging that the law was “both discriminatory and profoundly unfair to dying patients at the most critical time of their life”.

In the US, legislation around end-of-life care explicitly bans euthanasia, and only mentally-sound, terminally-ill patients can access a doctor’s prescription for medication they may decide to take to peacefully end their suffering if it becomes unbearable.

New York introduced legislation to allow medical aid in dying laws in 2016. The bill, which narrowly scraped through the health committee by 14-11, would require a patient to make a signed and dated request for the prescription witnessed by at least two individuals who vouch for their capacity to make an informed decision. It has been stalled in the state assembly since 2021.

Critics of medical aid in dying laws argue that those affected by disability or depression could be coerced into making the decision to end their lives, saying there were too few safeguards, and that it diminishes self-determination.

Ms Sandeen says that opposition to the death with dignity movement were typically well-funded national organisations with religious affiliations who “cloaked their messages in slippery slope arguments”.

According to analysis of medical aid in dying in Oregon shows there have been few complaints about coercion.

In 2019, the outgoing Disability Rights Oregon executive director (DRO), which has federal watchdog powers, wrote that he had never knowingly received a single complaint in the 22 years he’d been in the role that a person with disabilities were being coerced to end their lives.

Compassion and Choices provided data showing that in nine states where with end of life legislation, 37 per cent of terminally ill patients who were prescribed a lethal drug didn’t end up taking the medication.

Advocates argue that simply by having the prescription on hand, and knowing they can use it should the pain become too great, is an immense palliative relief in itself.

In 2021, 383 Oregonians were issued with prescriptions, but only 238 of those were used, including 20 who had been prescribed the drug in previous years.

Supporters of medical aid in dying also want to see the word “assisted suicide” removed from descriptions of the practice.

They point to legislation which specifically prohibits suicide in several state laws.

And if a terminally ill person uses medical aid in dying, the death certificate does not list the cause as suicide, but rather the underlying disease the person was suffering with.

For groups like the Swiss-based Dignitas, everyone who is suffering from a terminal illness should be entitled to the right to die on their own terms, in their own home.

“Dignitas’ aim is not that people from all over the world travel to Switzerland, but that other countries adapt their laws to implement end-of-life-options so that people have a choice and do not need to become a ‘suicide tourist’,” a spokesperson for the Swiss-based group told The Independent.

And Pegasos “strongly” recommends patients should inform family members if they decide to take their life.

“Discussing your plans with family members may lead to people saying what needs to be said before you go,” its website states.

“This helps bring closure and is infinitely better than leaving a life unspoken for and full of regret.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments