‘When second plane struck we knew we were a nation at war’: How 9/11 changed America forever

Impact of that terrible day still reverberating in countless ways, writes Andrew Buncombe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ellen Saracini’s final words to her husband – and his to her – could not have been simpler: “I love you.” Saracini’s husband, Victor Saracini, was a pilot with United Airlines, and that morning he was in the cockpit of UA flight 175 from Boston to Los Angeles. As everyone would later reflect, it started out as a stunning, cloudless, blue-sky day.

“It was September and we had a pool in the back yard and the pool wasn’t closed. He was telling me ‘All right, remember to do this, remember to do that.’ He travelled all the time. I did that stuff all the time,” she told a CBS reporter years later. “His parting words and my parting words were, ‘I love you’.”

The couple did not fight often, she said. And she was “very glad” they did not that morning, when he called her at their home in Lower Makefield Township in Pennsylvania. Saracini and his 65 passengers did not make it to Los Angeles, or to whatever they hoped the future held for them that day. Thirty minutes into the flight from Logan international airport, al-Qaeda hijackers stormed the cockpit, killed Saracini and the first officer, and took control of the Boeing jet. At 9.03am, they flew it into the south tower of the World Trade Centre in New York City.

Of all the moments of horror and anguish that played out so publicly on 11 September 2001, first to the residents of America’s largest city and thence rapidly to the world, the attack on the south tower perhaps marked the moment people were forced to forgo any notion that this was anything other than a terror attack.

As it was, another hijacked plane, American Airlines flight 11, had already struck the north tower 17 minutes earlier. Yet amid the confusion, and in light of initial reports that the first incident had involved a much smaller plane, there was the perception – or the hope, at least – that it was an accident. When a second plane hit the south tower, any doubt disappeared. “As Victor’s plane struck, we realised we were a nation at war,” his widow tells The Independent.

More than two decades on, seeking to trace the shuddering impacts of the attacks, which involved four hijacked planes and killed around 3,000 Americans, is a challenge on many fronts. Partly that is because they affected people differently: the experience of someone watching on television in Omaha, Nebraska will have been different from that of any of the thousands of emergency responders and firefighters who rushed to the scene, gulping in toxic dust and smoke – some of which, even now, remains embedded in their bodies.

Then there is the fact that, even a generation on, the reverberations of the day are still being felt. It has affected domestic politics as well as the way in which America engages with the world. It was striking that several of the 13 US marines killed in 2021 in a suicide attack at Kabul airport – among the last of more than 100,000 troops first dispatched to Afghanistan a month after 9/11 – were born in 2001. They are part of a generation that has no “where were you on 9/11” experience to recount.

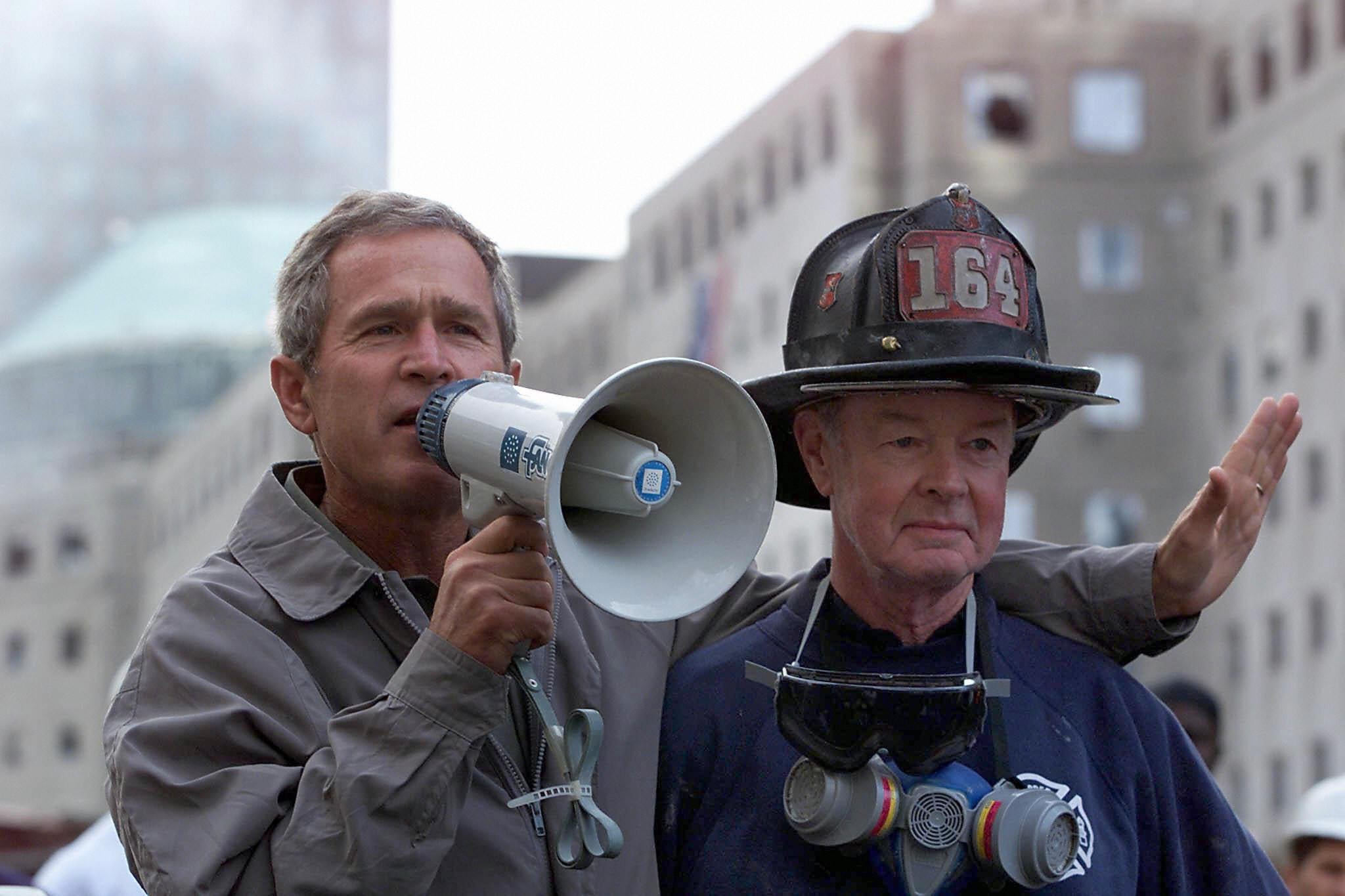

‘The people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon’

Some of the stuff is easy enough to narrate. Grieving, vulnerable and seeking revenge, the US rapidly responded with its military might. President George W Bush, bullhorn in hand as he toured the rubble of Lower Manhattan three days after the towers fell, vowed that “the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon”. His vice-president, Dick Cheney, warned that in pursuing al-Qaeda, America would have to operate on the “dark side”.

Within days, Congress, with a solitary “no” vote coming from Democratic congresswoman Barbara Lee, granted Bush the war-making powers that would allow him to order the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Bush took these powers and ran with them, launching what became known as the “war on terror”: not simply a series of military operations and a demand for vassalage from nations such as Pakistan – “You’re either with us or you’re against us” – but a green light to torture for the CIA, and a network of bases and prisons outside the US, most notoriously Guantanamo Bay, where human rights and the rule of law mattered for little.

Hundreds of thousands of civilians, in countries ranging from Iraq to Libya, as well as thousands of US and coalition troops, lost their lives.

Congress passed other laws, too, with scant or little scrutiny, including the Patriot Act, which was used by the government to spy on its own citizens, very often Muslims, with minimal oversight. (In the following years, the New York City Police Department, which on 9/11 was under the control of mayor Rudy Giuliani, would pay out many thousands of dollars to settle lawsuits brought in respect of surveillance operations against Muslims.)

At the time, the vast majority of Americans supported what Bush did: his approval rating soared to 86 per cent, and Republican strategist Karl Rove would use the “war on terror” to ensure Bush’s re-election three years later. Yet in many ways, the country did not feel any safer. In November 2001, American Airlines flight 587 crashed in the New York borough of Queens after taking off from JFK international airport. All 260 people on board were killed. A decade later, recalling the incident, the Associated Press reported that, despite the tragedy, once terrorism had been ruled out as the cause, “the country breathed a sigh of relief”.

Steel Standing

Antony Whitaker was among the thousands of New Yorkers who rushed to help that day. He was not a firefighter or a medic, but a specialist sent to the still-burning ruins by the utility company Con Edison to make safe live electrical wires that were exposed and sparking. Amid scenes he still finds hard to describe, there was something in particular that caught his eye: it was part of the south tower, the one into which UA flight 175 had been flown. Somehow, around 18 storeys of the building, or at least its steel frame, still stood.

Speaking to The Independent in 2021, Whitaker, now in his late 50s, says he could see the outline of the structure lit up by the arc lights being used by emergency teams. Somehow, amid the misery and death, that piece of battered debris projected a sense of defiance and even hope. As he says, it was literally “steel still standing”. A week later, Whitaker, who is also an artist, had the opportunity to go back and take a photograph, using his Canon EOS 620. A week after that, the structure was pulled down.

Whitaker, who has a son and lives in Harlem, used the photograph, which he called Steel Standing, as a vehicle through which to promote a message of unity. He raised funds for a foundation, and even helped push for the wearing of masks during the pandemic. He has presented copies of the photograph to everyone from Colin Powell, Bush’s secretary of state, to Ban ki-Moon.

How does Whitaker think America has most changed since he took the image? The world – and America with it, he says – has shrunk. Social media has brought the opportunity to connect, but has also forced people to think about places such as Afghanistan in a way they did not in 2001. “We’re not as isolated as before, and I think that’s a major thing,” he says. “[They were places] we wouldn’t pay that much attention to. Today I think people pay a lot more attention, because of the potential terrorist situation.”

Whitaker, who is African American, says one aspect of America that has been too resilient is racism. Another constant – a positive one – is his belief that artists have a duty to respond, whether to events such as 9/11 or, a generation later, when rioters, some decked in the confederate flag, stormed the US Capitol. Art, he says, is the alchemy that transforms people’s experiences and presents them in a way that can be processed and considered: “All tragedy has to be responded to artistically,” he says.

‘There are reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say’

In the first anguished days and weeks following the al-Qaeda assault, America often felt feverish. In New York, people posted “Missing” posters containing the hopeful and unknowing faces of loved ones lost in the twin towers, who in all likelihood were dead. At the Pentagon – and in the rural town of Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where the last of the hijacked planes came down – officials sought to locate and preserve any remaining piece of debris. Much had been turned to ash.

Quickly, the drums for war sounded – and there were unlikely cheerleaders. On David Letterman’s Late Show, CBS journalist Dan Rather wept with the host, saying that he himself wanted to join the military. As Rather later conceded, such unquestioning patriotism did perhaps not best serve the country – let alone the media. It would later make it much easier for Bush to push for war in Iraq on false intelligence. Yet in the weeks and months after the attacks, few journalists questioned the government’s actions, and even cartoonists who dared not to pursue a pro-war line found themselves in little demand by commissioning editors.

Comedians such as Bill Maher, who suggested that, whatever else one called the hijackers, they were not “cowards”, received a rebuke from White House spokesperson Ari Fleischer. “There are reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say, watch what they do,” he said from the briefing room podium. “This is not a time for remarks like that. There never is.”

‘We wanted to turn some tragedy into at least something good’

Some Americans sought to learn more about the region of the world from where the attack against them had been launched, and wondered whether the US’s own actions in the world had played some role in triggering the terrorists. Eugene Steuerle lost his wife Norma, a clinical psychologist, when the plane on which she was traveling – the hijacked American Airlines flight 77 – was flown into the Pentagon.

On the same day, Joyce Manchester and David Stapleton lost four close friends, all members of the same family, who were on the plane. All of the passengers were killed, along with 125 people who had been at work at the Department of Defence headquarters. Steuerle, Manchester and Stapleton, all of them economists from Washington DC, wanted to identify a positive way to remember those they had lost.

In time, they established the Safer World Fund, which, with the help of the online crowdfunding platform Global Giving, raised and spent more than $2m on education for girls in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In August, the trio watched open-mouthed as the Taliban swept back to power in the country, threatening the work in which they had invested so much effort.

“After [my wife] died, we came into this money that came out of a 9/11 fund, and my kids and I didn’t really feel like we needed it, or necessarily deserved it,” Steuerle told The Independent from Alexandria, Virginia in 2021. “We weren’t being critical of others [who took the money].” He says that in addition to establishing a foundation in Alexandria, he worked with Stapleton and Manchester, whom he knew from economics forums, to turn “some tragedy into at least something good”.

Like many in Afghanistan itself, the three are now anxious as to whether their work will be permitted to continue. Either way, they have no regrets. Manchester says she was “very disappointed and frustrated, and upset that [the takeover] happened so quickly”, having expected – like many observers – that resistance to the Taliban might have been more stubborn. She adds: “I will say, I believe that women and girls are better off, because they’ve had the chance to be educated, and receive health care, and be out and about in the world.”

‘If you have a lap top, take it out of your bag’

The security staff who failed to stop the 19 Al-Qaeda hijackers, 15 of the from Saudi Arabia, were privately contracted by individual airports.

The changes have been largely successful. Once common, the hijacking of planes has dwindled in the years since 2001. There have been no such incidents in the United States, according to charity the Aviation Safety Network. Manufacturers strengthened cockpit doors to make it harder for potential hijackers to access controls. They did so under pressure from campaigners, among them Ellen Saracini.

She was hosting a meeting for volunteers at her children’s school in Pennsylvania, when word reached them as to what was happening in New York. Somebody told her a small plane had flown into the north tower. Someone else said an American Airlines passenger plane was involved. So she “cancelled the meeting and went home and saw it on TV”.

At around 10.30am that day, she says, it was confirmed that her husband, a former navy aviator who loved his family and also loved to drive his Corvette and his motorcycle, had been killed. A week later, Saracini and her daughters, Brielle and Kirsten, attended a memorial mass for her husband, where the 51-year-old pilot received a US navy honour guard. At its conclusion, Saracini was handed a tightly folded US flag.

She says she did not know then that she would dedicate herself to improving airline safety, or that the government, or the industry, would be so slow to act. It was only when she learned that cockpits were so vulnerable to being attacked – something she says airlines such as Israel’s El Al realised long ago, and acted to counter – that she launched a campaign that continues today.

In 2019, she was permitted some small cheer when Congress passed the Saracini Aviation Safety Act, requiring all new aircraft to be fitted with a second cockpit door. Yet Saracini says her work is not done. The 2019 law only applied to new aircraft; she says given the Federal Aviation Administration has acknowledged that cockpit doors remain vulnerable, all operating planes should be required to have a second door.

She has been working with her congressman, Republican Brian Fitzpatrick, to push through a new measure. “We can agree that September 11 changed the world. And there are things about September 11 that haven’t been answered yet, haven’t been disclosed, haven’t been protected again,” she says. “So that’s my part of standing up to right the wrongs. And I won’t stop. You know, the flight crews, Victor’s brothers and sisters, are still in the air flying. And they’ve become my brothers and sisters. We can’t leave them vulnerable up there.”

This article was originally published in 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments