How 9/11 changed the world, from American civil liberties to the Middle East

Two decades on from the terror attacks,The Independent looks at how the events of September 11, 2001 still reverberate globally

People often ask: “Where were you on 9/11?”

For a generation, the day has acted as a marker: in an individual sense, but also in a collective one, by the nature of its inclusivity. Everyone remembers where they were, in the way that other generations recall the moment they learned of the assassination of president John F Kennedy.

Around 3,000 people were killed by al-Qaeda hijackers, who seized four passenger planes and flew them into World Trade Centre’s twin towers, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania.

Much of our memory of that day is centered on New York City, its familiar skyline ravaged by explosions and fireballs; of people falling to their deaths, and of vast buildings transformed into ash. We remember courageous firefighters rushing in to help as dust-caked New Yorkers watched in dazed horror.

The Independent’s New York correspondent David Usborne, having hurried to the scene, found himself among those running for safety when the towers fell that morning. At dawn the following day, he walked through the area that was being called ground zero. “If I ever need to imagine what a nuclear hell must look like, I have seen it today,” he wrote.

Yet the al-Qaeda attacks, like a dropped crystal wine glass shattering into a thousand splinters, reverberated globally. They certainly changed America, and its then president, George W Bush, who launched a so-called “war on terror” and green-lit the use of torture to try to counter the al-Qaeda militants. And they instantly affected the way we travel and board planes.

As our international correspondent Borzou Daragahi writes, one of the sharpest impacts was felt in the Middle East, where civilians watched the news, fearful the attack would prompt a rapid and overwhelming American military response. They were correct. Within a month, the US and its allies invaded Afghanistan, and later Iraq.

So while it is correct that we remember the 3,000 killed in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania – among them 70 Britons – it is essential, too, that we devote time to telling the stories of the hundreds of thousands killed in the military response that followed, be they families lost in the “shock and awe” bombing of Baghdad or a Pakistani teenager killed by a drone strike.

By doing so, we can connect their stories with those of the families who, every year, leave flowers and American flags alongside the names inscribed in the dark granite at the 9/11 Memorial Museum in Lower Manhattan.

A challenge for journalists trying to trace the arc of 9/11 is that the narrative is still moving. As defence correspondent Kim Sengupta reports from Afghanistan, 20 years later, the Taliban is once again in charge of Kabul. However, already we see young women protesters determined to stand up to the Taliban’s strictures, insistent that, for them, history will not simply play on a loop.

As the US made its final evacuation of troops and civilians from Afghanistan last month, Isis suicide bombers struck, underscoring the fact that the threat from terrorism remains largely unchecked. It was also striking that several of the US marines who were killed by the bomb alongside more than 100 Afghans were born in 2001. They were of the generation that grew up after 9/11, and yet even they are now part of its story.

(Andrew Buncombe)

... America

By Andrew Buncombe

Ellen Saracini’s final words to her husband – and his to her – could not have been simpler: “I love you.” Saracini’s husband, Victor Saracini, was a pilot with United Airlines, and that morning he was in the cockpit of UA flight 175 from Boston to Los Angeles. As everyone would later reflect, it started out as a stunning, cloudless, blue-sky day.

“It was September and we had a pool in the back yard and the pool wasn’t closed. He was telling me ‘All right, remember to do this, remember to do that.’ He travelled all the time. I did that stuff all the time,” she told a CBS reporter years later. “His parting words and my parting words were, ‘I love you’.”

The couple did not fight often, she said. And she was “very glad” they did not that morning, when he called her at their home in Lower Makefield Township in Pennsylvania. Saracini and his 65 passengers did not make it to Los Angeles, or to whatever they hoped the future held for them that day. Thirty minutes into the flight from Logan international airport, al-Qaeda hijackers stormed the cockpit, killed Saracini and the first officer, and took control of the Boeing jet. At 9.03am, they flew it into the south tower of the World Trade Centre in New York City.

Of all the moments of horror and anguish that played out so publicly on 11 September 2001, first to the residents of America’s largest city and thence rapidly to the world, the attack on the south tower perhaps marked the moment people were forced to forgo any notion that this was anything other than a terror attack.

As it was, another hijacked plane, American Airlines flight 11, had already struck the north tower 17 minutes earlier. Yet amid the confusion, and in light of initial reports that the first incident had involved a much smaller plane, there was the perception – or the hope, at least – that it was an accident. When a second plane hit the south tower, any doubt disappeared. “As Victor’s plane struck, we realised we were a nation at war,” his widow tells The Independent.

Twenty years on, seeking to trace the shuddering impacts of the attacks, which involved four hijacked planes and killed around 3,000 Americans, is a challenge on many fronts. Partly that is because they affected people differently: the experience of someone watching on television in Omaha, Nebraska will have been different from that of any of the thousands of emergency responders and firefighters who rushed to the scene, gulping in toxic dust and smoke – some of which, even now, remains embedded in their bodies.

Then there is the fact that, even a generation on, the reverberations of the day are still being felt. It has affected domestic politics as well as the way in which America engages with the world. It was striking that several of the 13 US marines killed last month in a suicide attack at Kabul airport – among the last of more than 100,000 troops first dispatched to Afghanistan a month after 9/11 – were born in 2001. They are part of a generation that has no “where were you on 9/11” experience to recount.

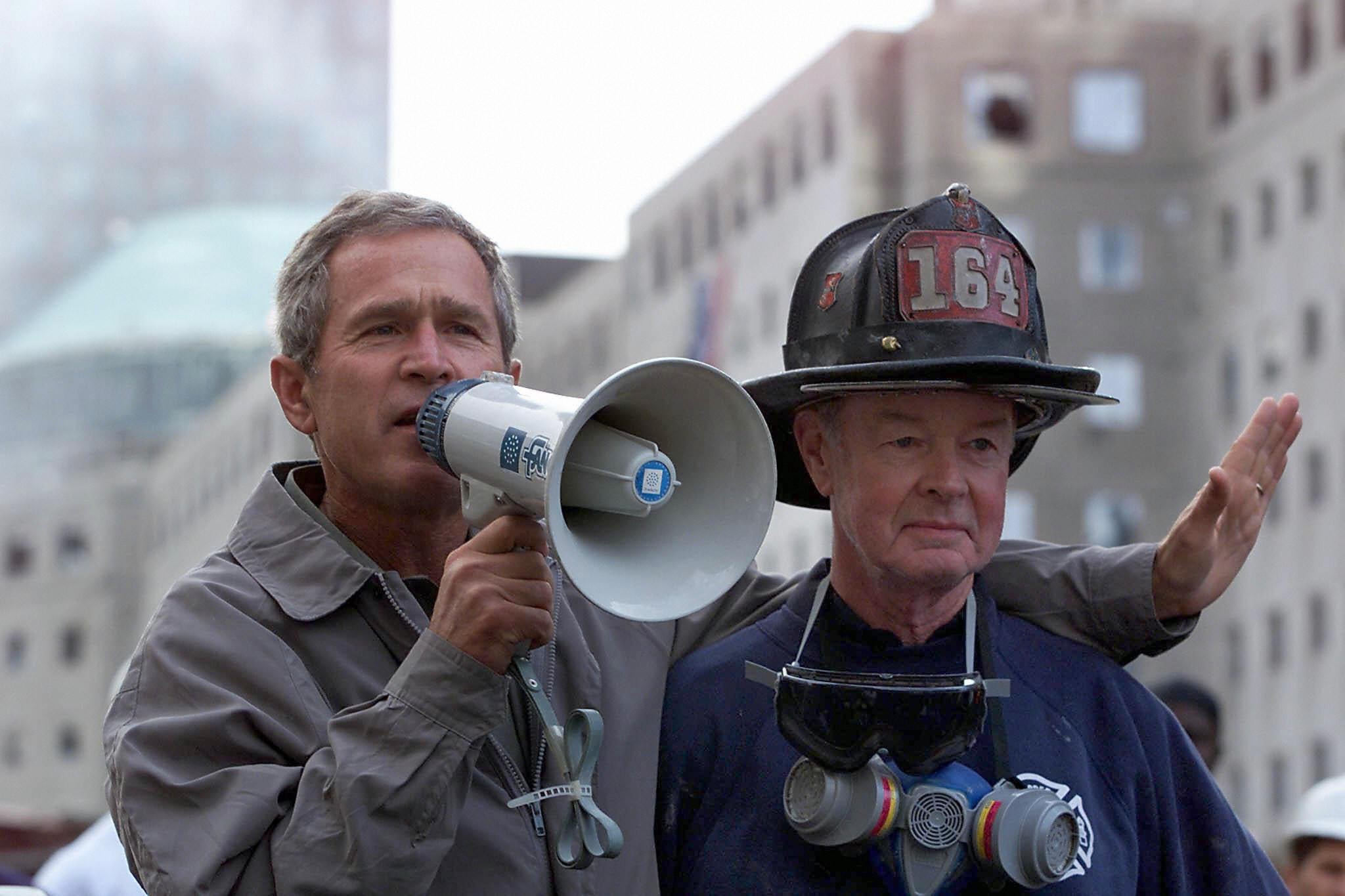

‘The people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon’

Some of the stuff is easy enough to narrate. Grieving, vulnerable and seeking revenge, the US rapidly responded with its military might. President George W Bush, bullhorn in hand as he toured the rubble of Lower Manhattan three days after the towers fell, vowed that “the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon”. His vice-president, Dick Cheney, warned that in pursuing al-Qaeda, America would have to operate on the “dark side”.

Within days, Congress, with a solitary “no” vote coming from Democratic congresswoman Barbara Lee, granted Bush the war-making powers that would allow him to order the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Bush took these powers and ran with them, launching what became known as the “war on terror”: not simply a series of military operations and a demand for vassalage from nations such as Pakistan – “You’re either with us or you’re against us” – but a green light to torture for the CIA, and a network of bases and prisons outside the US, most notoriously Guantanamo Bay, where human rights and the rule of law mattered for little.

Hundreds of thousands of civilians, in countries ranging from Iraq to Libya, as well as thousands of US and coalition troops, lost their lives.

Congress passed other laws, too, with scant or little scrutiny, including the Patriot Act, which was used by the government to spy on its own citizens, very often Muslims, with minimal oversight. (In the following years, the New York City Police Department, which on 9/11 was under the control of mayor Rudy Giuliani, would pay out many thousands of dollars to settle lawsuits brought in respect of surveillance operations against Muslims.)

At the time, the vast majority of Americans supported what Bush did: his approval rating soared to 86 per cent, and Republican strategist Karl Rove would use the “war on terror” to ensure Bush’s re-election three years later. Yet in many ways, the country did not feel any safer. In November 2001, American Airlines flight 587 crashed in the New York borough of Queens after taking off from JFK international airport. All 260 people on board were killed. A decade later, recalling the incident, the Associated Press reported that, despite the tragedy, once terrorism had been ruled out as the cause, “the country breathed a sigh of relief”.

Steel Standing

Antony Whitaker was among the thousands of New Yorkers who rushed to help that day. He was not a firefighter or a medic, but a specialist sent to the still-burning ruins by the utility company Con Edison to make safe live electrical wires that were exposed and sparking. Amid scenes he still finds hard to describe, there was something in particular that caught his eye: it was part of the south tower, the one into which UA flight 175 had been flown. Somehow, around 18 storeys of the building, or at least its steel frame, still stood.

Whitaker, now aged 57, says he could see the outline of the structure lit up by the arc lights being used by emergency teams. Somehow, amid the misery and death, that piece of battered debris projected a sense of defiance and even hope. As he says, it was literally “steel still standing”. A week later, Whitaker, who is also an artist, had the opportunity to go back and take a photograph, using his Canon EOS 620. A week after that, the structure was pulled down.

Whitaker, who has a son and lives in Harlem, used the photograph, which he called Steel Standing, as a vehicle through which to promote a message of unity. He raised funds for a foundation, and even helped push for the wearing of masks during the pandemic. He has presented copies of the photograph to everyone from Colin Powell, Bush’s secretary of state, to Ban ki-Moon.

How does Whitaker think America has most changed since he took the image? The world – and America with it, he says – has shrunk. Social media has brought the opportunity to connect, but has also forced people to think about places such as Afghanistan in a way they did not in 2001. “We’re not as isolated as before, and I think that’s a major thing,” he says. “[They were places] we wouldn’t pay that much attention to. Today I think people pay a lot more attention, because of the potential terrorist situation.”

Whitaker, who is African American, says one aspect of America that has been too resilient is racism. Another constant – a positive one – is his belief that artists have a duty to respond, whether to events such as 9/11 or, a generation later, when rioters, some decked in the confederate flag, stormed the US Capitol. Art, he says, is the alchemy that transforms people’s experiences and presents them in a way that can be processed and considered: “All tragedy has to be responded to artistically,” he says.

‘There are reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say’

In the first anguished days and weeks following the al-Qaeda assault, America often felt feverish. In New York, people posted “Missing” posters containing the hopeful and unknowing faces of loved ones lost in the twin towers, who in all likelihood were dead. At the Pentagon – and in the rural town of Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where the last of the hijacked planes came down – officials sought to locate and preserve any remaining piece of debris. Much had been turned to ash.

Quickly, the drums for war sounded – and there were unlikely cheerleaders. On David Letterman’s Late Show, CBS journalist Dan Rather wept with the host, saying that he himself wanted to join the military. As Rather later conceded, such unquestioning patriotism did perhaps not best serve the country – let alone the media. It would later make it much easier for Bush to push for war in Iraq on false intelligence. Yet in the weeks and months after the attacks, few journalists questioned the government’s actions, and even cartoonists who dared not to pursue a pro-war line found themselves in little demand by commissioning editors.

Comedians such as Bill Maher, who suggested that, whatever else one called the hijackers, they were not “cowards”, received a rebuke from White House spokesperson Ari Fleischer. “There are reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say, watch what they do,” he said from the briefing room podium. “This is not a time for remarks like that. There never is.”

‘We wanted to turn some tragedy into at least something good’

Some Americans sought to learn more about the region of the world from where the attack against them had been launched, and wondered whether the US’s own actions in the world had played some role in triggering the terrorists. Twenty years ago, Eugene Steuerle lost his wife Norma, a clinical psychologist, when the plane on which she was traveling – the hijacked American Airlines flight 77 – was flown into the Pentagon.

On the same day, Joyce Manchester and David Stapleton lost four close friends, all members of the same family, who were on the plane. All of the passengers were killed, along with 125 people who had been at work at the Department of Defence headquarters. Steuerle, Manchester and Stapleton, all of them economists from Washington DC, wanted to identify a positive way to remember those they had lost.

In time, they established the Safer World Fund, which, with the help of the online crowdfunding platform Global Giving, raised and spent more than $2m on education for girls in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In August, the trio watched open-mouthed as the Taliban swept back to power in the country, threatening the work in which they had invested so much effort.

“After [my wife] died, we came into this money that came out of a 9/11 fund, and my kids and I didn’t really feel like we needed it, or necessarily deserved it,” Steuerle says from Alexandria, Virginia. “We weren’t being critical of others [who took the money].” He says that in additional to establishing a foundation in Alexandria, he worked with Stapleton and Manchester, whom he knew from economics forums, to turn “some tragedy into at least something good”.

Like many in Afghanistan itself, the three are now anxious as to whether their work will be permitted to continue. Either way, they have no regrets. Manchester says she was “very disappointed and frustrated, and upset that [the takeover] happened so quickly”, having expected – like many observers – that resistance to the Taliban might have been more stubborn. She adds: “I will say, I believe that women and girls are better off, because they’ve had the chance to be educated, and receive health care, and be out and about in the world.”

‘If you have a lap top, take it out of your bag’

The security staff who failed to stop the 19 al-Qaeda hijackers were privately contracted by individual airports. One of the most enduring changes triggered by the attacks was an overhaul of airline safety, and the creation of a new agency, the Transportation Security Agency (TSA). Nowadays it can come as a surprise to remember that baggage checks back then were cursory, and that passengers could carry on bottles, knives and even cigarette lighters in their hand luggage.

The changes have been largely successful. Once common, the hijacking of planes has dwindled in the years since 2001. There have been no such incidents in the United States, according to charity the Aviation Safety Network. Manufacturers strengthened cockpit doors to make it harder for potential hijackers to access controls. They did so under pressure from campaigners, among them Ellen Saracini.

She was hosting a meeting for volunteers at her children’s school in Pennsylvania, when word reached them as to what was happening in New York. Somebody told her a small plane had flown into the north tower. Someone else said an American Airlines passenger plane was involved. So she “cancelled the meeting and went home and saw it on TV”.

At around 10.30am that day, she says, it was confirmed that her husband, a former navy aviator who loved his family and also loved to drive his Corvette and his motorcycle, had been killed. A week later, Saracini and her daughters, Brielle and Kirsten, attended a memorial mass for her husband, where the 51-year-old pilot received a US navy honour guard. At its conclusion, Saracini was handed a tightly folded US flag.

She says she did not know then that she would dedicate herself to improving airline safety, or that the government, or the industry, would be so slow to act. It was only when she learned that cockpits were so vulnerable to being attacked – something she says airlines such as Israel’s El Al realised long ago, and acted to counter – that she launched a campaign that continues today.

In 2019, she was permitted some small cheer when Congress passed the Saracini Aviation Safety Act, requiring all new aircraft to be fitted with a second cockpit door. Yet Saracini says her work is not done. The 2019 law only applied to new aircraft; she says given the Federal Aviation Administration has acknowledged that cockpit doors remain vulnerable, all operating planes should be required to have a second door.

She is working with her congressman, Republican Brian Fitzpatrick, to push through a new measure. “We can agree that September 11 changed the world. And there are things about September 11 that haven’t been answered yet, haven’t been disclosed, haven’t been protected again,” she says. “So that’s my part of standing up to right the wrongs. And I won’t stop. You know, the flight crews, Victor’s brothers and sisters, are still in the air flying. And they’ve become my brothers and sisters. We can’t leave them vulnerable up there.”

... Afghanistan

By Kim Sengupta

The anniversary of 9/11 will be marked by the humiliating retreat of the US and UK from Afghanistan, the country their forces invaded in response to the New York attacks, and the triumphant return of the Taliban two decades after its rule was overthrown. The defeat was the result of US president Joe Biden’s disastrous decision to carry out a hasty withdrawal of troops, which became a signal for the Islamists to launch their offensive, bringing about the swift collapse of the Afghan state.

Twenty years of hard-won gains in the country on a range of issues, including human rights – especially women’s rights – are now under threat, with the Afghan people and society being dragged back under harsh, primitive and brutal Islamist rule. The narrative of the “New Taliban”, reformed and no longer like its predecessor, has been severely dented, with its first government drawn from members of the old regime or their sons: all male and all Pashtun, with every other community excluded.

Among their first acts, the Taliban have told working women to stay at home, banned women from taking part in sports, segregated education, banned music, and banned protest marches against these measures. People have sought to vote with their feet. The evacuation of those offered refuge abroad, a horrendously chaotic process, has seen an exodus of the skilled and the educated, while others, trapped, are seeking desperately to escape.

There have been a series of arrests and disappearances, despite the Taliban’s assurances that they would not seek retribution against their opponents. One of the broader strategic reasons given by the Biden administration for the pullout – that the US would be better placed to counter the challenge from China and Russia without distractions in Afghanistan and the Middle East – has not stood up to its first test. Instead, Beijing and Moscow have been clear winners from the west’s departure from Afghanistan, with both countries pledging to enlarge their footprints.

The new Taliban regime has declared that China will be its principal ally

A potent symbol of the influence of these new players is the plan to base Chinese troops and engineers at Bagram. US troops slunk away from the airbase, one of the centres of the west’s counter-insurgency missions, without informing their Afghan allies.

Biden had originally chosen 9/11 as the symbolic date for the troops’ withdrawal. He was not to know, of course, that the ending would be so inglorious. But the US president seemed to be in denial as the scale of what was going on unfolded. “I want to talk about happy things, man,” Biden complained at the 4 July press conference when asked about rapid Taliban advances. Five days later, he declared, in answer to another Afghan question: “The likelihood there’s going to be the Taliban overrunning everything and owning the whole country is highly unlikely.”

The war need not have ended so embarrassingly for the US, or so painfully for the Afghans. The security presence for the last six years – around 2,400 Americans, just under a thousand from Nato and 750 from the UK – was an insurance against the insurgents as well as the elements of Pakistan’s military and its intelligence service, ISI, that fed and watered them.

This was thrown away by the Trump administration at the ineptly handled talks in Qatar that resulted in the shoddy Doha Agreement. Biden is now busy claiming that he inherited the bad deal from former president Donald Trump, despite the fact that throughout the US presidential campaign, he had repeatedly affirmed that he would not reverse the pullout decision.

But Biden had done nothing since getting to the White House about the repeated breaches of the agreement by the Taliban, which could have allowed the US to review its own position.

The US troops left before the end of August, with Biden refusing to extend the deadline for evacuation. This effectively meant that other countries had to end their airlift as well, as the airport could not be held without the American military. The result is that hundreds of those in danger from the Islamists had to be left behind and, at the moment, have little chance of getting out.

The evacuations ended with horrific violence: a suicide bombing by Isis-K that killed 170 people, including 13 US troops. The killings were a reminder that the Taliban are not the only violent Islamists in the country. The Haqqani network, now in government, has links with al-Qaeda. Isis-K has been carrying out massacres for the last few years, but their victims were Afghan and thus the group was only of passing interest to the west.

Biden may well find that abandoning Afghanistan does not actually take him to a happy place for long. The west has walked away from Afghanistan before, after using the mujahideen against the Russians. We know what happened then: from ungoverned space emerged terrorist camps, al-Qaeda, and 9/11.

The overthrow of Taliban rule following 9/11 was a time of great hope and expectation. Some of us who have been in Afghanistan in the last two months, witnessing the traumatic end of America’s longest war, were also there then, seeing the rebirth of a nation. Colour and light broke through the suffocating, joyless years of Islamist rule. There was music, shops opened, bright posters appeared, women threw off their hijabs. Girls’ schools and language schools sprang up, while modern subjects were introduced into colleges and universities.

People who had fled to Pakistan, Iran and further afield began to return to help rebuild the country. Osama bin Laden had fled to Pakistan after the Americans failed to kill or capture him in Tora Bora, as had the Taliban leadership. There was, at the time, an attempt by some in the Pakistani leadership to hold talks with the US and the UK, but they were rebuffed.

George W Bush assured the Afghans at the time, “You can count on the United States: we shall be staying to ensure security.” Tony Blair declared that “this time we will not walk away”, acknowledging what had happened after the mujahideen’s war with Russia. But the US and the UK walked away again, this time into the disaster of the Iraq war in 2003. Funds for reconstruction were switched over: thinly spread forces were denuded even further. The Taliban, backed by their Pakistani sponsors, moved back into the security vacuum, taking over rural districts and carrying out attacks in the cities.

American and British politicians appeared oblivious to what was happening. Donald Rumsfeld, the US defence secretary at the time, told us in Mazar-e-Sharif that the war was over: “The Taliban are finished, they are marginalised, they will have no future role to play in Afghanistan.” In 2006, with the security situation fraying, the west and its allies were back in Afghanistan with the establishment of Isaf (the International Security Assistance Force). At the request of the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, British troops in Helmand were sent to small towns to set up bases, effectively challenging the Taliban to a fight.

Soon Helmand was aflame, as was Kandahar next door where a Canadian force was now in place. The Americans were fighting elsewhere, and the French, Italians and Germans faced varying degrees of violence in the regions where they were based. The conflict spread across the country; there were troop “surges” under US generals David Petraeus and Stan McChrystal. Biden, as the then president Barack Obama’s vice-president, was strongly opposed to sending in extra forces, but he lost the argument.

Biden visited Kabul to hector Karzai and other politicians on governance. He was right to do so. Massive amounts of international money had poured in, and corruption had become endemic, taking place on a massive scale in the senior ranks. The heroin trade was flourishing among politicians and warlords, often with the connivance of the Taliban. Huge garish buildings, “narcotecture”, sprang up in Kabul, some of them rented out to international organisations.

The war continued. The insurgents were driven out of areas they had occupied, but there were never enough troops to hold the ground. In any event, it was impossible to defeat an insurgency as long as it had sanctuary and support across the border. Isaf ended its military mission in 2013, with a relatively small force staying on. A stalemate had been reached, with the Taliban holding swathes of the countryside, while the government held cities and towns. Western casualties were minimal.

Then Trump, who had pledged to bring to troops home, began negotiations with the Taliban, excluding the Afghan government, and signed the Doha deal – which gave the Taliban virtually everything they wanted – and Biden went along with the withdrawal of forces, with the consequences we now see. Afghanistan, from where the 9/11 attacks were planned, has become the place, 20 years on, where the reputation of the US has become tarnished, leaving allies deeply worries and adversaries emboldened.

... the Middle East

By Borzou Daragahi

Like the rest of the world, the people of the Middle East and North Africa were mesmerised and horrified by the spectacle of 9/11 as they watched it unfold that Tuesday evening on their televisions. But even as the wreckage of the Twin Towers in lower Manhattan smouldered, they faced a unique terror.

American newspapers were decrying the attack as “a day that would live in infamy,” echoing US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call to arms after the 7 December 1941 Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbour. And very quickly, there was a fear that al Qaeda’s attack would prompt a muscular, potentially devastating American military response in the Middle East.

In Baghdad, as news of the attacks spread, shops and roadways emptied, and residents stayed inside their homes. “I was traveling to my house, and nobody was moving on the ground—there were only security patrols,” recalls one Iraqi who lives in the capital. “Everybody was expecting an attack in seconds.”

The dread was well-founded. Within hours of the 9/11 attacks, while he was still helping survivors of the wreckage at the Pentagon, then US Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld began agitating his underlings to come up with ways to link the attacks planned by Osama bin Laden to Iraq and others, according to notes taken by the aide and obtained by CBS News.

“Go massive,” the notes quote him as saying. “Sweep it all up. Things related and not.”

Lukman Faily, now Iraq’s ambassador to Germany, was living in exile in the United Kingdom at the time and sensed right away that a day of reckoning had arrived. “I know Americans and how America works and what happens if you are on the wrong side of them,” he says in an interview. “It was clear to me from day one that this was a Pearl Harbour moment. It was a Middle East moment.”

Americans and the UK had already been regularly bombing Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War, meant to reverse President Saddam Hussein’s annexation of Kuwait. A punishing 1998 four-day bombing campaign codenamed Desert Fox had taken out much of Saddam’s air defences.

The newly elected Bush had brought on a clique of hawkish, ambitious Washington foreign policy fixtures obsessed with the Middle East and the Muslim world. They saw Iraq as a place to implement their vision. “9/11 becomes the Pearl Harbour that that group was looking for, that says now we can move against Iraq,” the noted historian of war and war culture John W. Dower said in a lecture at MIT.

In the 18 months between the 9/11 and the ultimately disastrous 2003 US invasion and occupation, the dread only grew as US policymakers made tortured cases to the world trying to connect Saddam to 9/11 and to the secret accumulation of weapons of mass destruction.

French President Jacques Chirac, who had served as an officer in the French occupation of Algeria, urged President George W. Bush to stay away. Arab League secretary general Amr Moussa predicted that a US invasion would “open the gates of hell.” German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder warned the war would “lead to the deaths of thousands of innocent children, women and men.”

The quick, violent “shock and awe” invasion was compounded by the disastrous aftermath. Americans attempted to occupy and administer a nation they knew next to nothing about, and on the cheap. Looting continued for weeks. Fires burned. The entire Iraqi state unraveled, then collapsed after US viceroy Paul Bremer disbanded the Iraqi army, a flawed institution that nonetheless held the nation together.

“There’s a firm understanding that it was not managed very well,” says Faily, who also served as Baghdad’s envoy to Washington and has met with the senior US and Iraqi officials over the last 20 years. “‘Reckless’ may not be the right word, but not really calculating. The Americans did not do their homework, and the Iraqis suffered from it.”

No weapons of mass destruction were found. Bush finally admitted in 2006 that Saddam had nothing to do with 9/11 and his enablers never made a persuasive case that he had any operational ties to Al Qaeda.. But by then, Iraq had become a magnet for Al Qaeda, with a growing insurgency as well as a sectarian civil war.

The invasion by the West of an Arab land inspired jihadis from all over the world as well as angry Iraqis to take up arms against an occupier holed up behind fortresses made of blast walls and barbed wire. The incompetence and mismanagement left ungoverned spaces that allowed armed extremist groups to flourish, especially after the collapse of government control in neighbouring northern Syria gave birth to the Al Qaeda offspring, Isis, which prompted yet another war in Iraq.

A misbegotten and poorly planned war in response to an attack by al Qaeda cost tens of thousands of lives, and tragically, actually gave al Qaeda and its cousins far more potential recruits and spaces to grow.

Few Iraqis now care about 9/11, reflecting an apathy even resentment about the commemoration that is widespread throughout the Middle East and the Arab world. In Baghdad the big worries are getting enough electricity and water, as well as a recent spike in terrorism, including a suspected Isis attack near the northern city of Kirkuk last week that killed 13 people.

“All I can say,” says Heba Fahed, 34, a mother of four, “is that on September 11, 2001, we were living much more safely and securely than today.”

... American values

By Richard Hall

It was just four months after the September 11 attacks that the first prisoners arrived at the US naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Some 20 prisoners from the battlefields of Afghanistan were led from a cargo plane in handcuffs, their faces and eyes covered, to a new kind of detention facility.

A photograph released a week later by the US navy of those same prisoners in distinctive orange jumpsuits, on their knees and watched over by their captors, would endure for years after. The number of prisoners would swell and the facility would become synonymous with torture, rendition and human rights abuses – those images were a potent symbol of it all, of a changing America, one that had forgotten its own values as it set out on a quest for vengeance.

Barack Obama summed up the feeling shared by many on the campaign trail in 2007, shortly before he won the presidency. “In the dark halls of Abu Ghraib and the detention cells of Guantanamo, we have compromised our most precious values,” he said.

The Bush administration’s decision to use torture began with the capture of a man US officials described as the first “high-value detainee” of the War on Terror. Abu Zubaydah, a Palestinian national captured in Pakistan in March 2002, was said to have been a senior al-Qaeda operative – an accusation that later turned out to be false. He was accused of having information about future attacks against the US and so was handed over to the CIA. He would become the first person to face the “enhanced interrogation” techniques deployed by the CIA.

Waterboarding, sexual harassment and abuse, physical abuse and sleep deprivation were all approved by the US government for use against detainees. Guantanamo Bay became the lightning rod for the torture programme, but most of the abuses took place at so-called CIA “black sites” around the world – secret jails outside the rule of law. Some 50 sites in 28 countries were thought to have been used for the programme.

Most of the torure took place behind closed doors in these highly secretive sites, but the world was given an insight into the kind of abuses taking place in US jails overseas with the explosion of the Abu Ghraib scandal in May 2004. The jail outside Baghdad had been a notorious torture centre under Saddam Hussein, and became so again when the invading US forces reopened the facility to hold captured fighters and terror suspects.

Former prisoners first alleged serious abuses by US forces in 2003. Investigations were launched quietly and charges were filed against the perpetrators, before images of the abuses were leaked to The Washington Post the next year. They revealed US soldiers engaged in the dehumanising abuse of detainees. Prisoners were stripped naked and photographed piled on top of each other. They were covered in human excrement and set upon by dogs, while US soldiers stood alongside them and smiled for the camera.

The “war on terror” became synonymous with torture. The initial outpouring of sympathy for the US following the 11 September attacks began to fade as the excesses of that global campaign began to take hold. According to Pew Research, a median of 50 per cent across surveyed nations said the US torture programme against suspected terorrists was not justified, while only 35 per cent said it was.

At home in the US, it was a different story. Opinion polls found significant support among Americans for the kind of interrogation and torture used by the CIA around the world in pursuit of terror suspects. In a Pew Research poll in July 2004, 43 per cent of Americans agreed that the torture of suspected terrorists to gain important information is often or sometimes justified – that number has now grown to a slight majority.

The 9/11 attacks also led to a shift in America’s values regarding liberty and the relationship of citizens with the state. The share of Americans who believed it was necessary for the average person to give up civil liberties in order to curb terrorism rose from 39 per cent in 1997 to 55 per cent in 2002, according to Pew Research. The attacks also changed how Americans treated each other. Islamophobia spiked across the US in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and hate crimes against Muslims rose by 500 per cent between 2000 and 2009, according to data from Brown University.

The US torture programme was consistently justified by its defenders, inside and outside government, as a necessary evil and a strategy to balance the security of US citizens and the values that they hold dear. But it later became clear that the underlying premise of those extraordinary measures – that they provided actionable intelligence that saved American lives – was flawed.

A Senate report on the programme, released in 2014, found that it was more brutal and far less effective than the CIA had claimed. Senate intelligence committee chair Dianne Feinstein said that torture “regularly resulted in fabricated information” and that the CIA was “often unaware the information was fabricated”. In a summary of the findings, she said that the torture programme had been found to be “morally, legally and administratively misguided”.

As the years went by, prisoners who were held for years without charge at Guantanamo Bay were quietly released or transferred to third countries. Many of them were never convicted.

By the time of the release of the torture report, the perception that the US had abandoned its principles in the quest for revenge was no longer controversial. Addressing the findings of the report, Senator John McCain, who was tortured by the North Vietnamese after his plane was shot down during the Vietnam war, echoed the words of his former opponent, Barack Obama: “But in the end, torture’s failure to serve its intended purpose isn’t the main reason to oppose its use. I have often said, and will always maintain, that this question isn’t about our enemies: it’s about us. It’s about who we were, who we are and who we aspire to be. It’s about how we represent ourselves to the world,” he told the Senate floor

"We have made our way in this often dangerous and cruel world, not by just strictly pursuing our geopolitical interests, but by exemplifying our political values, and influencing other nations to embrace them. When we fight to defend our security we fight also for an idea, not for a tribe or a twisted interpretation of an ancient religion or for a king, but for an idea that all men are endowed by the Creator with inalienable rights. How much safer the world would be if all nations believed the same. How much more dangerous it can become when we forget it ourselves even momentarily.”

... The GOP

By Eric Garcia

In the summer of 2001, US president George W Bush’s administration considered allowing more than 3 million undocumented immigrants from Latin American countries to secure legal status in the United States.

But when terrorists attacked the United States at the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, and had their plot thwarted in Pennsylvania, it changed the trajectory of how the Bush administration and the Republican Party would approach immigration. In the 20 years following 9/11, the Republican Party’s response would change the makeup of its party coalition, and subsequent events would fundamentally alter the party into becoming more nativist and exclusionary towards immigrants, all culminating in the current iteration of the GOP.

Julian Zelizer, a professor of history at Princeton University, says that 9/11 in some ways proved politically beneficial for Republicans, as it led to increasing electoral success for the GOP and solidified their majorities in Congress. In 2002, Republicans broke the traditional trend of the party in power losing seats when it gained seats in both the house and the Senate. It did so largely by portraying Democrats as being soft on national security. Perhaps most infamously, in Georgia, Saxby Chambliss beat Sen Max Cleland, who had lost both his legs and his right forearm serving in Vietnam, largely on the back of an ad that opened with Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein.

The election also marked the final chapter of the Republicans’ takeover in southern states, which had begun in the 1960s and accelerated in earnest in the 1980s, as they won over the remaining white formerly Democratic voters, defeating incumbent Democrats in states like South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Democrats have since failed to win governorships in any of these states.

“The sorting of the parties, which was under way in 2001, is now complete,” says John Pitney, a professor at Claremont McKenna College. Mr Pitney adds that the party has become far more conservative: “There are no liberals in the Republican Party.” But after Mr Bush’s re-election in 2004, American dissatisfaction with the war in Iraq would lead to Barack Obama’s election. Mr Obama, who was a Democrat, frequently criticised the war, saying the United States “took our eye off the ball”. Mr Obama would also later order the operation that killed Bin Laden.

In turn, Donald Trump’s campaign in 2015 vocally criticised the war in Iraq and frequently used it as a point to knock Mr Bush’s brother Jeb Bush, who was his opponent for the GOP nomination. “Politicians learn right away that they can openly question what was hereto seen as Republican doctrine,” says Suhail Khan, who served in the Bush administration. “And not only that, but they can succeed And there was an appetite to reassess and withdraw with some degree from these military forays.”

Similarly, Mr Zelizer notes that the GOP response to 9/11 bred an appetite for the nativism within the Republican Party that would animate its members.

While Mr Bush supported immigration reform, his administration also created the Department of Homeland Security, and would face a revolt from the party in trying to find a path to legalisation for undocumented workers. In 2007, his proposed legislation, which would have offered legal status to undocumented immigrants, died in the Senate, with all but 12 Republicans voting against it. Sen Jeff Sessions of Alabama was one of the leading voices against the legislation, and when it failed he told The New York Times that supporters wanted to pass the bill “before Rush Limbaugh could tell the American people what was in it”.

Eventually, Donald Trump’s administration would use the Department of Homeland Security and the Justice Department, now led by Mr Sessions, to implement some of his most draconian measures on the US-Mexico border, such as the so-called “zero-tolerance” policies and the separation of families.

Similarly, while Mr Trump at least rhetorically rejected the concepts of the war on terror, such as nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan, he capitalised on the growing nativism within the party. In the days following the terrorist attacks, Mr Bush was quick to say that the United States was not at war with Islam, a claim repeated by Mr Obama after the Bin Laden raid. But during that time, Mr Trump, then a reality television star, hinted that Mr Obama’s birth certificate might reveal that the president himself was a Muslim.

Mr Trump would go further when he ran for president in 2015, calling for a ban on Muslims entering the United States and saying he thought Islam hated the United States. But he could not have found much cache if there hadn’t already been fomenting anti-Muslim sentiment within the GOP. In the months after 9/11, the Pew Research Centre found that Republicans were only slightly more likely than Democrats to say that Islam encourages violence more than other religions. But that proportion would mushroom over the years.

When Mr Trump became president, he implemented a travel ban from countries with large Muslim populations, and repeatedly attacked Muslim members of Congress.

But while the GOP was almost entirely unified on how to confront the terrorist attacks on 9/11, it has been left split in the wake of the 6 January would-be insurrection. On that day, Rudy Giuliani, who after 9/11 was hailed as “America’s mayor” by the media, addressed a crowd of Trump supporters in support of what he called “trial by combat”, shortly before they raided the Capitol in an attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Meanwhile, Rep Liz Cheney – the daughter of Dick Cheney, who was vice-president in 2001 – voted to impeach Mr Trump for inciting the insurrection. Mr Giuliani is still widely welcomed within the party; Ms Cheney has been all but exiled.

... Travel

By Sunshine Flint

Gone were the Gothic arches at the base of the towers that echoed the ones in stone on the Brooklyn Bridge; gone was the steel tracery that drew a bow across the bridge’s soaring strings from the tip of Manhattan – a favourite tableau for snap-happy tourists, until that day. Gone were the red carpets in the lobbies where visitors took express lifts to the Top of the World observatory on the 107th floor of the south tower, or to a glamorous lunch at Windows on the World in the north tower, a restaurant so lofty that diners gazed at the curve of the earth from their table. The mourning was for the lives lost, of course, not for a tourist destination. But the destruction of these icons created a massive shock that was felt around the world.

In the immediate aftermath, that shock generated a massive change across all aspects of travel, most obviously seen in aviation and airport security. August 2001 had seen a record high of 65.4 million airline passengers. It took nearly three years for air travel to rebound, with that number being surpassed only in July 2004. Those passengers faced a very different experience from what the flying public had known before. Immediately, security lines at the airport became hours long, while the creation of the Transportation Security Administration in the US codified a way of flying that is now the norm.

Travellers today doff their shoes and jackets at security, pack no more than 100ml of liquid in their carry-ons, endure invasive pat-downs and enhanced body-scanners, all as a matter of course. Surveillance and tight visa restrictions are de rigueur, and international passengers flying into JFK and other US airports have their fingerprints placed on file and are subjected to more questioning by customs and immigration agents. Air travel was transformed, practically overnight, into something frustration-filled and complicated.

Meanwhile, in New York, nearly every institution, sporting event and cultural site had to rethink its security operations, from installing metal detectors and using bomb-sniffing dogs to banning water bottles. Some, like the Statue of Liberty, closed for years, while others, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reopened almost immediately, directed by the city to be open as a place of solace to New Yorkers.

“We reopened on the Thursday morning,” says John Barelli, chief security officer at the museum from 1986 to 2015 and author of Stealing the Show: A History of Art and Crime in Six Thefts. “We always had enough staff covering our entrances and galleries, we just retrained them. We instituted bag checks and electronic wanding at the entrances, for metal and weapons, at the three public entrances, and inspected every vehicle coming into the public garage. We did a lot more with the CCTV.” Like other major institutions, the museum also started receiving regular briefings from the FBI and NYPD’s Joint Terrorism Task Force.

Hotels had to make similar security assessments. “Hotels had drills with the task force and the FBI, and ramped up security in their lobbies, with some of the larger ones installing metal detectors,” recalls Vijay Dandapani, president and CEO of the Hotel Association of New York City. The detectors were scrapped quickly as hotels realised they sent the wrong message to guests about the safety of the city.

Air travel was transformed, practically overnight, into something frustration-fuelled and complicated

But as New York recovered, with its new security measures in place, fewer international tourists were there to see it. In 2000, there were more than 35 million visitors to New York City and, of those, 6.8 million were international tourists. In 2002 that number declined to 5.1 million and didn’t reach pre-2001 levels again until 2006.

International visitors are incredibly important to New York’s tourism industry, with the four top countries of origin being China, the UK, Brazil and France. Crucially, they spend more than domestic tourists. “While international travellers account for 20 per cent of visitors, they account for 50 per cent of spending,” says Christopher Heywood, EVP of global communications for NYC & Company. “They stay longer and they spend more while they’re here.”

In 2006, the Bloomberg administration and the city made a big push for travel and tourism, and NYC & Company opened offices around the world and launched global campaigns promoting the city. “We now have 17 international outposts and we highlight all five boroughs,” says Heywood. “Travel to all of them went up, particularly to Brooklyn and also Queens.”

Two decades later, the numbers have not only rebounded, but in 2019 the city had an all-time record high of 66.6 million visitors, 13.5 million of whom were international – double the 2000 numbers. Hotels also had a record 129,000 rooms in March 2020 and occupancy was at nearly 90 per cent, compared with the 9/11 dip to 65 per cent. “International visitors make up 25 per cent of our guests, and UK guests make up the largest percentage of revenue in that group,” says Dandapani.

As the city recovered, new hotels staked out territory across Manhattan. Firmdale Hotels opened the Crosby Street Hotel in 2009 in SoHo, its first in New York. “By the time we started that project, New York had bounced back, in particular downtown and SoHo,” says Craig Markham, director. “We always felt that it would be the perfect location for our first New York hotel, with its neighbourhood style similar to our London hotels.”

Hotels also opened across the river in Williamsburg, downtown Brooklyn and Queens, cool boroughs that foreign travellers wanted to explore. “The international market as a general rule is more intrepid than domestic travellers,” says Heywood. “They want to get on public transport and go deep into Brooklyn, to Coney Island, to the Rockaways. The Brits in particular are adventurous and want to explore the city.”

Now we need the resilience that got us through 9/11 and rebuilt our city

But underneath the record number of visitors, new hotel openings and discoverable neighbourhoods, a permanent change has come to the city. Some of it is visible, like the signs on the subway – “If you see something, say something”, and “Si ve algo, diga algo” – but some is less so, like the increased surveillance by intelligence and police. But the biggest change is the feeling that New York and New Yorkers will always have to live with the threat of terrorism and terrorist attacks. Polls over the last decade show that terrorism fears haven’t waned, and have even gone up at times.

Today, with Covid and the global pandemic, the city’s tourism has taken a harder hit than it did after 11 September. A number of hotels have permanently closed, reducing the number of rooms by 20,000; Broadway went dark for 18 months; Midtown restaurants are empty.

“We were the epicentre of Covid in the US and it just wiped out tourism in New York,” says Heywood. “Now we need the resilience that got us through 9/11 and rebuilt our city.”

But if 9/11 proved anything, it’s that New York will always be a place for travellers and tourists. And that, while its tragedies are a matter of fact, it remains an outward-looking city, a seaward-facing city – lamp lifted in perpetual and enduring welcome.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments