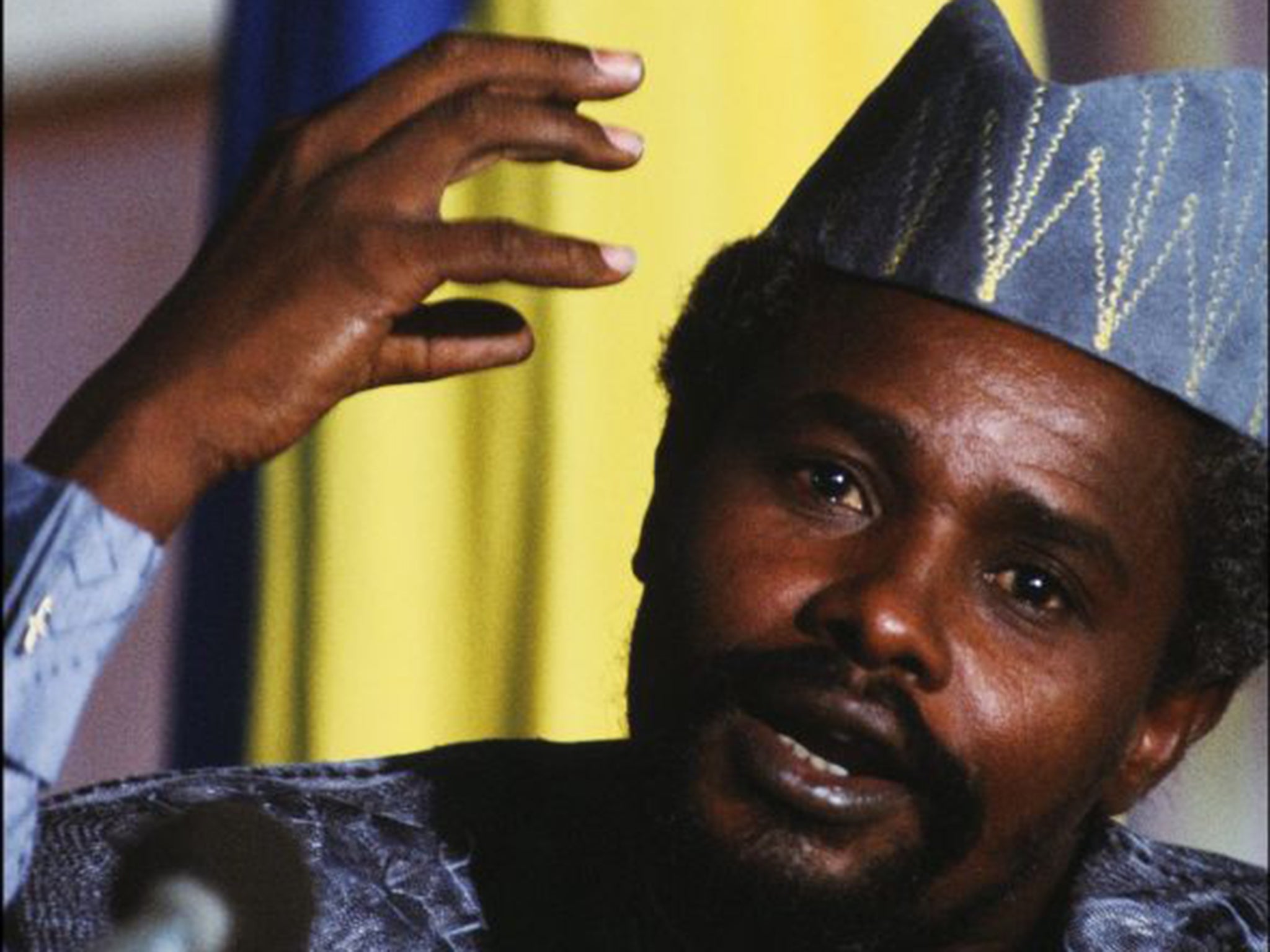

Trial of Chad's former dictator Hissène Habré: A turning point for African justice

It gives hope to torture victims across the continent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a long, dark night in 1988, in a stinking prison cell in N’Djamena, the capital of Chad, a man lay desperately ill, close to death.

Souleymane Guengueng had already watched his fellow prisoners die, in a cell so cramped their bodies were “lying on my legs”.

The beatings had begun almost as soon as he was picked up by the men from the DDS, the secret police of Chad’s US-backed dictator Hissène Habré. No reason had been given for his arrest: two secret policemen had simply strolled into the office where he had been working as an accountant and told him: “Come with us: our director needs some information from you.” Since then, Mr Guengueng had watched as others were called from their cells in the dead of night by a police chief, never to be seen again.

On starvation rations, in cells without toilets, in filth that bred disease, no prisoner in the Camp des Martyrs was under any illusion about his ultimate fate.

“We were effectively dead,” said Mr Guengueng. “The conditions were created for us to die.”

And now it appeared to be his turn, an abdominal infection that had been left to fester in the prison the last straw for his weakened body. “My cellmates later told me I stopped breathing. They thought I was dead. But I came back. By a miracle, I had survived.

“That was when I realised that God had saved my life and given me a mission. I vowed that if God let me live, I would fight to let the world know the truth, about what we suffered, for me, for my fellow prisoners, for those who died.”

It has taken 17 years, the collection, with others, of some 700 witness testimonies – in the face of repeated kidnap or murder attempts by Habré’s henchman – but Mr Guengueng may finally be about to fulfil his vow.

Tomorrow, in the Palais de Justice in Dakar, Senegal, Mr Guengueng, 64, will watch the former dictator enter the dock to be tried on charges of crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture.

It is a moment many thought would never happen. This, after all, was the dictator said to have been feted by the Reagan-era CIA as “the quintessential desert warrior”, the perfect bulwark against Colonel Gaddafi in neighbouring Libya – whatever he did to his own people.

Such was his aura of invincibility, Mr Guengueng said, that when men in uniform came to release him after the 1990 coup that deposed Habré, “we thought they were going to shoot us. We just couldn’t believe Habré would ever leave power.”

Now, though, Habré may be about to become “Africa’s Pinochet”.

The former Chilean president’s arrest in London in 1998 and the subsequent House of Lords ruling that he could be tried for crimes such as torture, had been a “wake-up call for dictators”. That, though, had been driven by the developed world, by a Spanish magistrate issuing an international arrest warrant that was acted upon in London.

The trial of Habré, in Senegal, where he had been enjoying a comfortable exile, would take things to a new level, said Reed Brody, legal counsel for Human Rights Watch. He said: “This is the case that shows it is possible for African victims to bring African dictators to justice in Africa. It doesn’t show it will be easy. It doesn’t show it will be quick. But it does show that dictators who commit atrocities will never be fully out of the reach of justice.”

The ripples were already being felt, said Mr Brody, in Senegal for the conclusion of a case on which he has worked for 16 years. “Yesterday I walked out of a meeting and an exile from Gambia approached me and asked if we could take action against [President] Yahya Jammeh. There have been emails from Ethiopia about [former President] Mengistu….”

Mr Guengueng still retains the politeness that probably got him arrested by Habré’s secret police that morning in August 1988. His mistake had been to greet fellow Chadians and invite them indoors while temporarily living in Cameroon at the height of the Chad-Libya conflict.

“The DDS thought we had been plotting against Habré,” he said. “It was false. I had simply welcomed my fellow Chadians into my home in a spirit of hospitality.

“But when I told my interrogator I knew nothing, I was put in a cell.”

He recovered from the infection, but there would be more horrors during two and a half years in five different prisons.

“In one prison, there were more than 100 of us to a cell. When someone died, the guards would leave it a day before removing the corpse. They wanted us to smell the stench. We would push the body into a corner. If you needed to sleep, you would have to rest your head against the body. There was no other space.”

But the joy of returning alive to his wife and children was not enough. Once released, Mr Guengueng started collecting testimony from fellow former prisoners. It was no easy matter. Habré may have gone, but his henchmen remained, often still in the same positions of power.

“My friends told me I was mad,” he said. Masked men threatened him. His car was tailed. “But I couldn’t stop. I had made my vow.”

He wasn’t alone. When Jacqueline Moudeina, the Chadian lawyer representing Habré’s alleged victims, enters the Palais de Justice tomorrow, she will do so with shrapnel in her leg, the legacy of a 2001 grenade attack on a crowd of demonstrators by supporters of the former dictator.

Mr Brody, once given the sobriquet “the dictator hunter”, also played his part. In 2001, curiosity led him to enter the now derelict, abandoned headquarters of the DDS.

He and his colleagues stumbled upon piles of dust-covered documents, comprising lists of prisoner names, interrogation reports, and 1,265 direct communications to Habré himself about the status of 898 detainees. “It was totally unexpected,” said Mr Brody. “And it was the smoking gun.”

Mr Guengueng’s team spent six months painstakingly photocopying every document.

When Habré enters court tomorrow, he said, “I hope I can come face to face with him, and ask why he made us suffer so”.

Most of all, though, he hopes that the mission he gave himself after surviving a desperate night in a squalid prison cell will finally be accomplished – “that the whole world will know the truth”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments