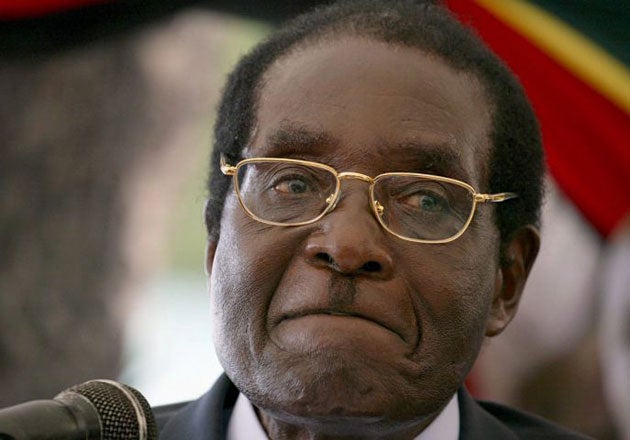

The most fragile of deals: Mugabe finally cedes power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For 28 years, Robert Mugabe has reigned like an absolute monarch. The power-sharing deal to be signed on Monday in theory closes that chapter in Zimbabwe's troubled history. It whittles down his powers in key respects. But some analysts are unsure whether the complex arrangement brokered by South African President Thabo Mbeki will hold together long enough to produce effective government.

The octogenarian President will now have to contend with a cabinet dominated by the combined factions of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). Authoritative sources say the deal to be announced on Monday creates 31 cabinet posts, of which Mr Mugabe will pick up 15, Morgan Tsvangirai 13, and the remaining three will go to a smaller breakaway faction of the MDC led by Arthur Mutambara.

However, contrary to suggestions that Mr Mugabe's role will be reduced to a ceremonial one, he will very much remain in the driving seat as President and head of cabinet.

"If the two MDC factions work together, which they must in the national interest, they will enjoy a majority in cabinet," said David Coltart , the legal affairs secretary of Mr Mutambara's smaller splinter faction. This means the MDC should be able to drive the policy agenda and seek to abolish the apparatus of repression that Mr Mugabe has nurtured over the years. But there is also the real possibility that the MDC factions might remain at loggerheads, which will effectively benefit Mr Mugabe.

Some analysts see a major bottleneck emerging from the complex institutional arrangements created to mollify both the Mugabe and Tsvangirai sides during months of negotiations.

The dialogue had remained stalled over Mr Tsvangirai's refusal to deputise Mr Mugabe as chair of cabinet. The MDC leader had contended that as Prime Minister, the prerogative of chairing and overseeing the work of cabinet should be his. The 84- year-old President argued that stripping him of the chairmanship of cabinet would reduce him to a "ceremonial drama queen".

The stalemate was broken by Mr Mbeki, who proposed two centres of power, instituting a new "council of ministers" while keeping the normal cabinet. Mr Mugabe and his two deputies will have no seats in the council of ministers chaired by Mr Tsvangirai. Mr Mugabe would remain chair of the cabinet and the "council of ministers" would be accountable to cabinet. The council will be charged with recommending policy to cabinet and overseeing its implementation.

Potential for conflict thus remains high, notes an analyst, Noah Chifamba. "What happens if Mugabe rejects policy proposals from the council and vice-versa? It is not clear whose decisions take precedence," he said. Eldred Masunungure, a political scientist at the University of Zimbabwe, said: "It's a potential minefield and some very treacherous terrain will have to be navigated." Mr Coltart echoed that fear, noting that most opposition cabinet members would at one stage have been "brutalised on the instructions of those they will now have to work with".

The power-sharing deal calls for a new "people-driven" constitution to be enacted within 18 months and for the way to be prepared for future elections under a new democratic dispensation. If the latter is achieved, that will perhaps be the most significant outcome of the deal as it will enable the opposition to fight and win future elections with ease.

More important is the share- out of powerful security cabinet portfolios. It is understood that the MDC has been allocated the Ministry of Home Affairs in charge of the police. If the MDC can overhaul the force into a credible professional body, then it would have achieved a milestone in the re-democratisation process of Zimbabwe. The problem for Mr Tsvangirai is that he won't have power to hire and fire the police commissioner. Such key appointments will still be made by Mr Mugabe on the advice of the Prime Minister. Mr Mugabe would also retain the Ministry of Defence with all its power to annihilate his enemies still intact.

"I would agree that this [deal] is a fragile initial step and it won't work unless the political foes involved bury the hatchet and decide to just work for the good of the country," said Mr Chifamba, warning that any "minor irritation" from either of the parties could break it. "Let's give it a few months and see. I think if it survives the first three to six months, when important policy decisions will have to be taken, it will probably survive the duration of its envisaged existence."

Western donors, whose money will be required for reconstruction, are likely to adopt a wait-and-see attitude. Many, like the US and Britain, will be disappointed that Mr Mugabe still wields so much power.

The first task of the new government will be to come up with a viable economic reconstruction programme. Mr Tsvangirai will then have to embark on a resource mobilisation exercise to fund it. But getting agreement for such a programme, which would in some instances entail reversing many of Mr Mugabe's nationalisation laws, will be a mammoth task. Mr Mugabe has already declared there will be no going back on his land reforms despite the fact that once productive farms dished out to incompetent cronies are lying fallow.

At a glance, the national unity pact

*Positions

President: Robert Mugabe

Two Vice-Presidents: Both from Zanu-PF

Prime Minister: Morgan Tsvangirai

Two Deputy Prime Ministers from MDC

*Division of powers

Head of state and chairman of cabinet: Robert Mugabe

Chairman of council of ministers: Morgan Tsvangirai

*Responsibilities

Council of ministers debates and recommends policy to cabinet. It also oversees implementation of policy. Cabinet oversees the council and approves recommendations from council of ministers

*Control of ministries

31 ministries in total : 15 allocated to Mugabe, 13 to Tsvangirai, three to Arthur Mutambara (splinter MDC faction)

15 deputy ministers (eight to Mugabe, six for Tsvangirai and one for Mutambara)

Mugabe retains Ministry of Defence

Tsvangirai gets Ministry of Home Affairs

*Constitution

A new democratic constitution envisaged within 18 months of the start of the unity government

The Nkomo precedent

*The fate of Joshua Nkomo is a worrying precedent for Morgan Tsvangirai. In December 1987, Nkomo, leader of Zimbabwe's main opposition party, Zapu, signed an agreement with President Robert Mugabe for a national unity government.

Mr Nkomo, whose supporters in southern and western Zimbabwe had suffered years of political violence after independence, served as a figurehead vice-president.

The cabinet also included three Zapu leaders. The two parties were officially merged to become Zanu-PF, but in reality the deal led to the absorption of Mr Nkomo's party and enabled Mr Mugabe to rule unchallenged for a further decade. Mr Nkomo remained as vice-president until his death in 1999.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments