Hunger on the rise in South Sudan with 1.5 million on brink of starvation, despite peace deal

Another 6 million are facing extreme hunger, according to the UN – and there is a risk of famine if aid is not delivered, writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rebecca has eaten nothing for seven days. The emaciated mother of five, 38, recently injured her arm while gathering wild fruit – and in South Sudan‘s punishing dry season, this is all her family have lived off for months.

The injury means Rebecca is now unable to gather even the most basic sustenance for her children, all of whom are malnourished and suffering from diarrhoea.

Some families have resorted to tapping the blood of live cattle for sustenance – or even more creatively grim ways to survive.

Rebecca has been displaced multiple times in the country’s five-year civil war. After returning to Pibor, a remote town in the northeast, she is now camping in the grounds of a schoolyard built by rights groups.

“I have no home or house right now because of the conflict,” she says, propped up against the wall of the packed-mud shelter that she and her family call home.

“My husband is too old to work or help, it’s up to me. If someone doesn’t intervene and bring us food, all of us will starve to death.”

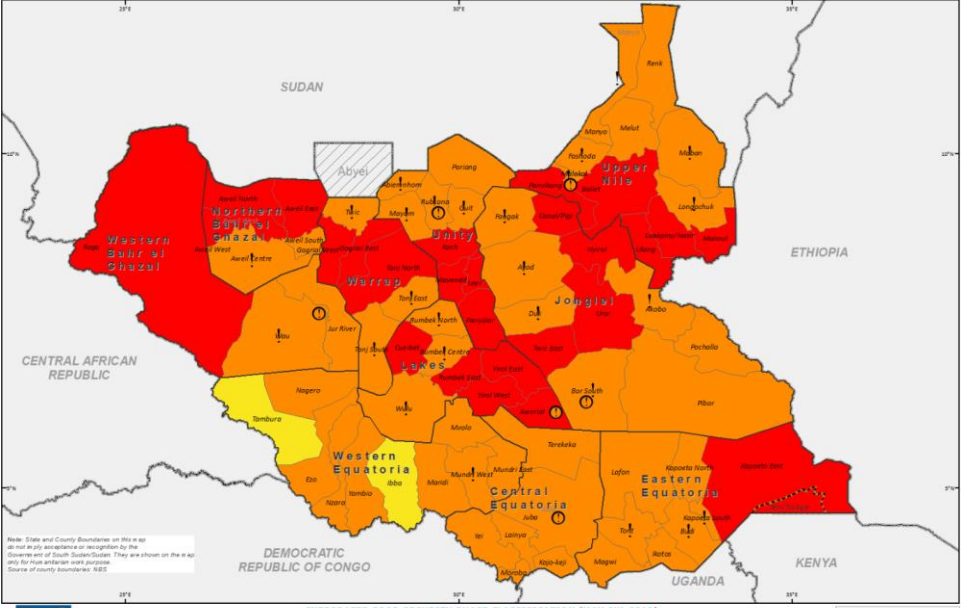

Pibor is one of the areas most blighted by hunger – the United Nations warned last week at least 45,000 people across the country could soon face famine.

Rebecca, who knows of three people who have died from hunger since December, fears she might not make it.

“I’m afraid I might die – famine here could easily be declared because of people who are starving to death,” she explains, labouring over her words.

“Our only hope is the international community. Without them we will not survive.”

Five months into a peace deal in war-ravaged South Sudan, 1.5 million people are on the brink of starvation, and more than 6 million people – two-thirds of the population – are facing extreme hunger, according to a UN report released last week.

That is a 13 per cent increase on the same period last year, even though an agreement between South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir and rebel factions was signed in September, and is still tentatively holding.

Right now at least 45,000 people are experiencing “catastrophe phase 5” famine-like conditions – mostly in Pibor and the Lakes states in eastern and central South Sudan.

That is likely to spike over the summer months when the country is at the height of its lean and dry season.

A devastating lack of funds is impeding the humanitarian response.

If there is no assistance from the international community, the UN predicts the number of people in famine could soar to a staggering 260,000.

Unicef, which reported that nearly 900,000 children under the age of five are severely malnourished, said its programme is just 15 per cent funded.

“[If] funding is not timely secured, the children we know how to save may not make it,” says Andrea Suley, a Unicef representative in South Sudan.

Mary, from Gumuruk, a small town only accessible by helicopter and a three-hour dirt-track drive, says she was forced to promise her 11-year-old daughter to a man twice her age, just to secure food for her starving family.

Wages are not increasing, the prices of food continue to soar, the scale of the displacement crisis means people have been forced away from their farms. It is extremely dire

The cattle dowry that the mother of nine was given in exchange for her daughter’s future hand in marriage kept them going for a while.

“I had to book my daughter’s hand in marriage because we were starving to death,” she tells The Independent.

“I know 10 people, all women and children who have starved to death since last year.”

Martha, 28, who was also living off berries in the Pibor area, said she knew of 20 people, including relatives, who had died since January 2018.

‘If there is no intervention it will continue, people will die of thirst and hunger,” she adds.

Famine was formally declared in South Sudan two years ago across counties in Unity state – the first anywhere in the world since Somalia’s crisis in 2011.

At the time, 3.9 million people – 40 per cent of the country – needed food aid. Now, it is over 6.4 million people. While famine pockets have yet to be officially noted this year, Simon Cammelbeeck, WFP’s acting country director warned there was “a real risk” of a new outbreak in areas that were already going hungry.

“Food insecurity is increasing in 2019,” he says. “Unless we scale up humanitarian and recovery activities soon, more and more people will be at risk.”

There are many reasons that this is happening.

Fighting still rages with rebel groups who are not signatories to the peace deal in areas such as Yei in the southwest. Where there is violence, aid agencies struggle to reach those in need.

Meanwhile, prolonged dry seasons, flooding, crop disease and pest infestation have blasted agriculture in the country.

Surging inflation, which hit over 800 per cent in October 2016, has seen food prices soar and market produce dwindle. Although inflation quietened to nearly 45 per cent in January, the knock-on effect continues to affect impoverished families who simply do not have the money to eat.

“The humanitarian situation hasn’t shifted in the same way that the political situation has,” says Elysia Buchanan, the policy advisor to Oxfam that runs several nutrition programmes in the country.

“Wages are not increasing, the prices of food continue to soar, the scale of the displacement crisis means people have been forced away from their farms. It is extremely dire,” she adds.

The rations have been cut, the country is in parts still at war, we cannot find work for ourselves

The return of refugees from abroad is also piling pressure on scant resources available, according to Manase Lomole, chair of South Sudan’s relief agency, the Relief and Rehabilitation Commission.

He said at least 140,000 people have returned to South Sudan since the peace agreement was signed.

“As a government, we cannot meet their needs alone – we need support from the international community,” he explains from his office in Juba.

In an UN-protected displacement camp in Juba – called POC site 3 – that lack in funding has seen food rations slashed by nearly half.

The camp is populated by people from the Nuer ethnic group, one of the 60 or so in South Sudan, most of whom fled their houses at the start of the civil war in 2013. The Nuer, who have been hardest hit by the war, fear they cannot return to their villages because their homes are occupied by regime forces.

“Rations have been reduced and so a lot of moderately malnourished people are becoming severely malnourished,” says Yvonne Rohan from Concern Worldwide, Ireland’s largest humanitarian agency, which runs clinics in the POC 3 and other sites.

In desperation, lactating mothers were using the food supplements the agency had given them to feed their families, she added.

Many were also sharing their scant supplies and ration cards with an increasing number of refugee relatives who had returned from abroad.

“There are new arrivals and we have no control over the registration,” Rohan adds.

Ban, 38, a grandmother who had not eaten properly in days, sits on the floor of Concern’s clinic with her grandson, who is showing the telltale signs of severe malnourishment, including a distended belly.

“The rations have been cut, the country is in parts still at war, we cannot find work for ourselves, we cannot return home because our homes are still occupied, my husband was killed,” she says, holding the emaciated child.

“I’m looking after seven children and am desperate.”

Back in Pibor, Rebecca says women are bearing the brunt of the food crisis as they are expected to not only source food for their families but often go hungry to make sure everyone has been fed.

“We are sick, helpless and homeless and I am on my own since my husband is very old,” she says.

“You will return here and see no population in this area. We need our help. If the international community does not come, we will starve to death.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments