Nelson Mandela legacy: What now for the continent he bestrode like a colossus?

He was both an inspiration and a reproach to his fellow African heads of state. But will the great man’s example continue to resonate, now that he is gone?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On one of the few occasions that Nelson Mandela addressed the quality of his fellow African leaders he did so to plead for understanding on their behalf. He reminded his admirers around the world that it was unreasonable to expect people who had grown up in hardship, sleeping on mud floors, not to succumb to the luxuries of office when they got there. It was impossible, he noted, for people who had come from such poverty not to seek material wealth for themselves and their families.

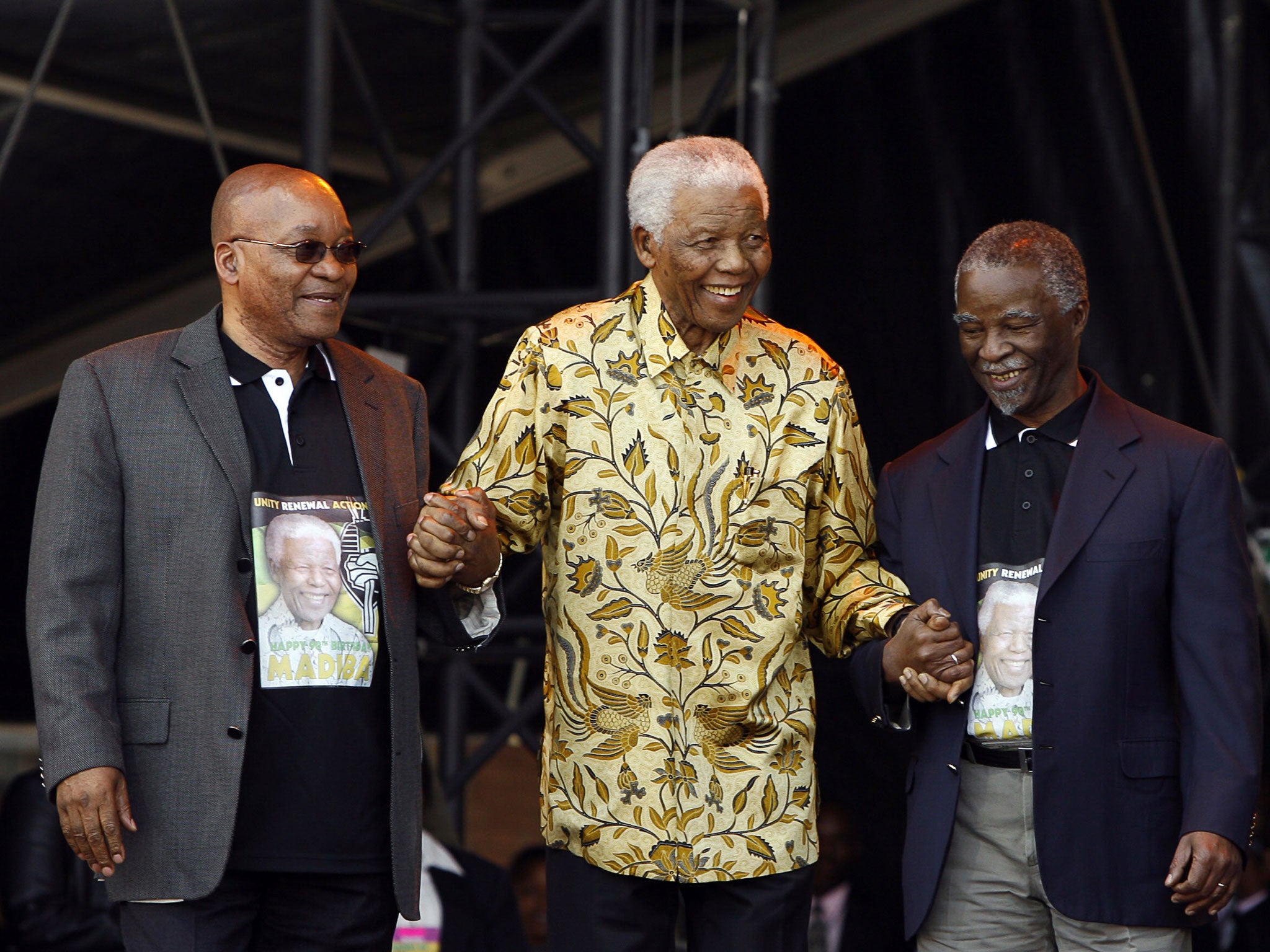

These words were spoken when Jacob Zuma was only a potential leader – but they fit comfortably as a description of the current head of the African National Congress and President of South Africa. It was perhaps the clearest indication that the anti-apartheid hero did not expect others to follow his example. And for the most part they have not.

South Africa’s eventual departure from white minority rule in 1994 meant that is was four decades behind many of its continental counterparts. The country’s problems were also of a completely different nature. The biggest economy in sub-Saharan Africa faced the challenge of including its black majority in the proceeds of an industrialised economy while much of the rest of the continent was trying to create an economic base from scratch.

While the erudite lawyer made his long walk to freedom much of the rest of the continent was settling into a different form of apartheid in which local, post-colonial elites were accruing wealth and power that would permanently separate them from the rest of their populations. They were never likely to heed his central messages of reconciliation, modesty and plurality.

In many senses Madiba, who took power on behalf of a downtrodden majority and then left office after a single term, belonged more to a miraculous universal narrative than an African one. His legacy was to change external attitudes towards the potential of African leadership. Without his example it is unlikely that Bill Clinton and Tony Blair would have trumpeted Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, Ethiopia’s Meles Zenawi and Mr Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, as “renaissance leaders”. While each deserves to be assessed on his own merits – Mr Kagame and Mr Meles failed by any measure as democrats but achieved serious poverty reduction in both their countries – they did not take up the visionary mantle of Mandela.

The true state of African leadership was revealed by a Sudanese-born billionaire and former British telecoms engineer, Mo Ibrahim. He decided to spend part of his fortune nudging African autocrats to behave more like the former inmate of Robben Island. His African leadership prize, set up in 2007, awards democratically elected leaders who advance their societies and honour term limits – in other words to emulate Mr Mandela, who was declared an honorary laureate. The award seeks to address the same issue of material wealth that the great man discussed by handing the recipient $5m (£3m) and a sizeable pension for life. Despite the scale of the rewards, it has been a discouraging effort. The prize has been awarded only three times in its seven-year existence due to a dearth of suitable candidates.

Two of the three Mo Ibrahim laureates have come from countries whose experience has little in common with the rest of Africa. Festus Mogae in Botswana, for example, oversaw modest progress in a country made wealthy by diamonds and unencumbered by the ethnic divisions that have haunted so many others.

Mr Mandela’s chosen replacement, Mr Mbeki, was not considered worthy of the award despite leaving office of his own volition, having lost control of the ANC in a bruising power struggle with Mr Zuma.

If Mr Mandela’s personal example was insufficient to change the nature of African leadership, his stewardship of the ANC was also unable to prevent the party from repeating the failings of other liberation movements. After the 1994 honeymoon ended and the Nobel Peace laureate stepped back, the ANC sank into the same circus of self-enrichment and empire building that consumed the moral authority of its counterparts such as Zanu-PF in Zimbabwe.

Mr Mbeki took office amid high hopes that his attention to detail and his technocratic mastery of policy would build on his predecessor’s extraordinary peacebuilding accomplishments and address the pressing need to deliver a post-apartheid dividend to the majority black South Africans. Instead his tenure was marked by a bizarre bout of denialism over the appalling scale of the HIV/Aids crisis and the swift descent into a power struggle with his deputy president, Mr Zuma.

The advancing corruption of the party was highlighted by a notorious arms deal in 1999 in which a Swedish firm was accused of providing sizeable kickbacks in return for the new government approving arms purchases. Andrew Feinstein, an ANC MP and the head of the public accounts watchdog Scopa, resigned when the party curtailed investigations into the arms deal.

Today, the ANC is in a parlous state. It is so clearly perceived as a means to milk the state that its own rank and file are prepared to murder each other in order to take a place at the public trough. Since 2011 in Mr Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal alone, 38 ANC members have been assassinated in political-related killings.

Mr Mandela’s fellow moral authority, Archbishop Desmond Tutu – another honorary recipient of the Mo Ibrahim prize – has already condemned the ANC and publicly backed Mamphela Ramphele, a respected academic and former partner of the anti-apartheid hero Steve Biko. Her party, Agang, which was launched just before Mr Mandela’s condition was revealed to have worsened, will not defeat the ANC at the coming election but it will join a strengthening opposition. Mr Zuma will almost certainly win re-election in 2015 having seen off a challenge from within the ANC, but he will not trouble the purse of Mr Ibrahim any more than he will rival the accomplishments or public affection of Mr Mandela.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments