Kenya has become a perilous place to be a teacher with the threat of al-Shabaab leaving young people in crisis

Nobody wants to work in the schools in the north-east of the country, leaving classrooms empty. Catrina Stewart reports from Mandera on how the gap is being filled

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Morning was several hours off when passengers boarded the ill-fated bus bound for Nairobi. Among them, teachers heading home for the long holidays started to doze off, others murmured quietly.

An hour into the journey from Mandera in northern Kenya, Osinga Atibu was awoken from his reverie by the sound of gunfire. Masked men, armed with rifles and rocket-propelled grenades, forced the driver to a shuddering halt. A short while later, the terrified passengers were ordered off the bus, non-Muslims singled out, and forced to lie face down on the ground.

Marked out for execution, Mr Atibu, 29, knew he had no choice but to make a run for it. “I knew I was next. Whether I ran or not, I knew I was going to die,” he recalled in a telephone interview from his home in western Kenya.

Twenty-eight Kenyans, 17 of them teachers, died in the massacre on 22 November 2014, almost all of them shot multiple times in the back of the head by gunmen from al-Shabaab, the Somali terror group. The attack, the culmination of escalating insecurity in north-eastern Kenya, triggered a mass exodus of teachers from the region, leaving behind empty classrooms and young people in crisis.

At the beginning of last year, nearly 700 non-local teachers failed to report for duty in Mandera County, a scene played out across the north-east. Although it had been partly anticipated, the scale of it was shocking. “Seventeen of our teachers didn’t turn up,” said Mohammed Ibrahim, deputy head of Moi Girls Secondary School. “It was devastating,” he added. Seven teachers were left to teach 12 classes.

If the schools looked to the government for help, they were disappointed. With teachers camped out for weeks at the headquarters of the Kenyan National Union of Teachers in Nairobi demanding a transfer to a safer part of the country, the state eventually granted their request.

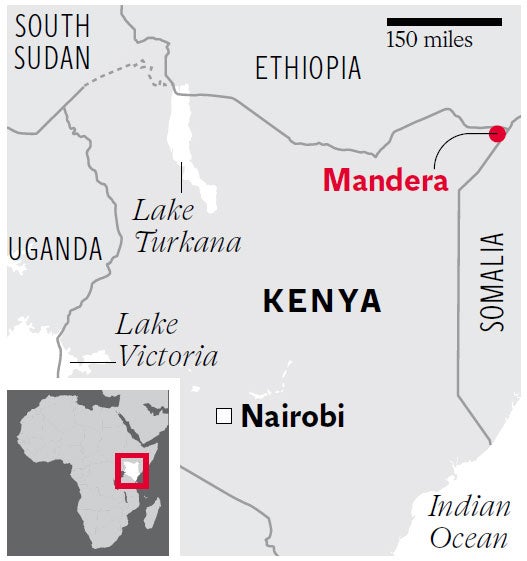

“If people think they are going to be killed, you can’t force them to come back,” said one representative of the national government in Mandera, who declined to talk on the record, citing the sensitivity of the issue. But others accused the government of letting the communities down. “The government was supposed to take action,” said Mr Ibrahim, “but instead they gave them [the teachers] a soft landing.” With Ethiopia to the north and Somalia to the east, the frontier town of Mandera feels like an extension of rural Somalia, the people here sharing both ethnicity and language with their war-torn neighbour. Its future hitched to Kenya’s by the British at independence in 1963, the region fought a four-year secessionist war, setting the tone for north-east’s neglect under successive Kenyan governments. Emergency rule, lasting nearly 30 years, was lifted in 1991.

Until a few months ago, there was only a skeleton police force here, its officers underpaid and poorly motivated. When the newly elected county government took office in 2013 – thanks to a new constitution that devolved power to the regions – the town, officials said, was largely in al-Shabaab hands.

“By 5pm [the police] retreated back to their camps,” said Ahmed Sheikh, a health official previously in charge of security. “That is when the terror group took control.” Few relished the prospect of a posting to Mandera, whether it was in education, health or government service. “Any government employee transferred to this part of the country feels they are being punished,” said Mr Ibrahim, the deputy head. The bus attack “came in handy”, he said, for those seeking a reason for transfer.

But Mr Atibu – who escaped the fate of the other non-local passengers by dashing for the bushes, the gunmen firing at him from behind – bridles at the suggestion that he and his fellow teachers took the decision to leave lightly. “The risks were everywhere,” he said. “We heard of people being shot here and there. With al-Shabaab, you never knew when they would come.”

Come again they did. Weeks after the bus massacre, gunmen swept down on a quarry near Mandera, shooting dead 36 miners as they slept. Al-Shabaab, retaliating for Kenya’s military presence in Somalia, aims to make the north-east “ungovernable”, the International Crisis Group said recently,

Yet not all of the teachers left. Samuel Wahome, 36, was one of the few non-locals to remain, a difficult decision given that his wife, also a teacher, left for her hometown with their young children to await a transfer. “It deeply affected me,” he said of the attack, which claimed the lives of three close friends. “But I picked myself up. Anything can happen anywhere. It’s just unfortunate that it happened here.”

But if the teachers have suffered, so too have the children. Even before the attacks, the north-east had some of the worst poverty indicators in the country, just over 40 per cent of primary-age children attending school, compared with a national average of 77 per cent. Nine per cent of children go on to secondary education, and of those who do, as little as 10 per cent achieve the grades to get into a Kenyan university. In just a few weeks, the county lost roughly half of its trained teachers. Counselling children who lost five of their teachers in the attack, Yusuf Bulle recalled the desolation of the children trying to make sense of the massacre.

“‘What bad thing did they do?’” they asked of the teachers who died. ‘What will happen to us? Will the schools open?’ I had to tell them the reality: the schools might open, but they might not have teachers.” Across the north-east, 95 schools shut their doors. Mandera’s county government for the most part avoided the same fate by drafting in retirees, officials, anyone with half an education to fill in – anything to keep schools open.

It also drafted in the brightest school-leavers, permitted by universities to pursue their studies during the holidays while they stood in for teachers during the term. If it were not for that, the situation would be much more dire, says Mr Wahome, who teaches physics, a skill in high demand. “The government does not give a damn,” he said. “It has lost touch with this place.”

Experts argue, however, that even the most enthusiastic and dedicated school-leaver is no substitute for the real thing. “If you have never had training, you won’t be that effective,” said Mr Bulle, a long-time educator in Mandera. “It’s better than nothing, but it won’t be as good as a real, trained teacher.”

While 150 students are set to start soon at a primary-teacher training institute opening in Mandera, the return of non-local teachers, particularly for secondary education, remains for many the best hope of securing their future. It is also critical, analysts warn, to prevent the spread of extremism.

Strides have been made on the security front – thanks in part to appointing those with Somali heritage to senior security positions – but the situation remains fragile.

Even though Mr Atibu has failed to find a job since leaving Mandera, he said that he could never return.

On Thursday, a Kenyan primary school teacher who recruited pupils into al Shabaab in Somalia was sentenced to 20 years in jail by a court in Mombasa. He used Islamic lessons to radicalise the children.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments