'Going after leaders is anti-African': The continent's heads of state threaten to break away from international court

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

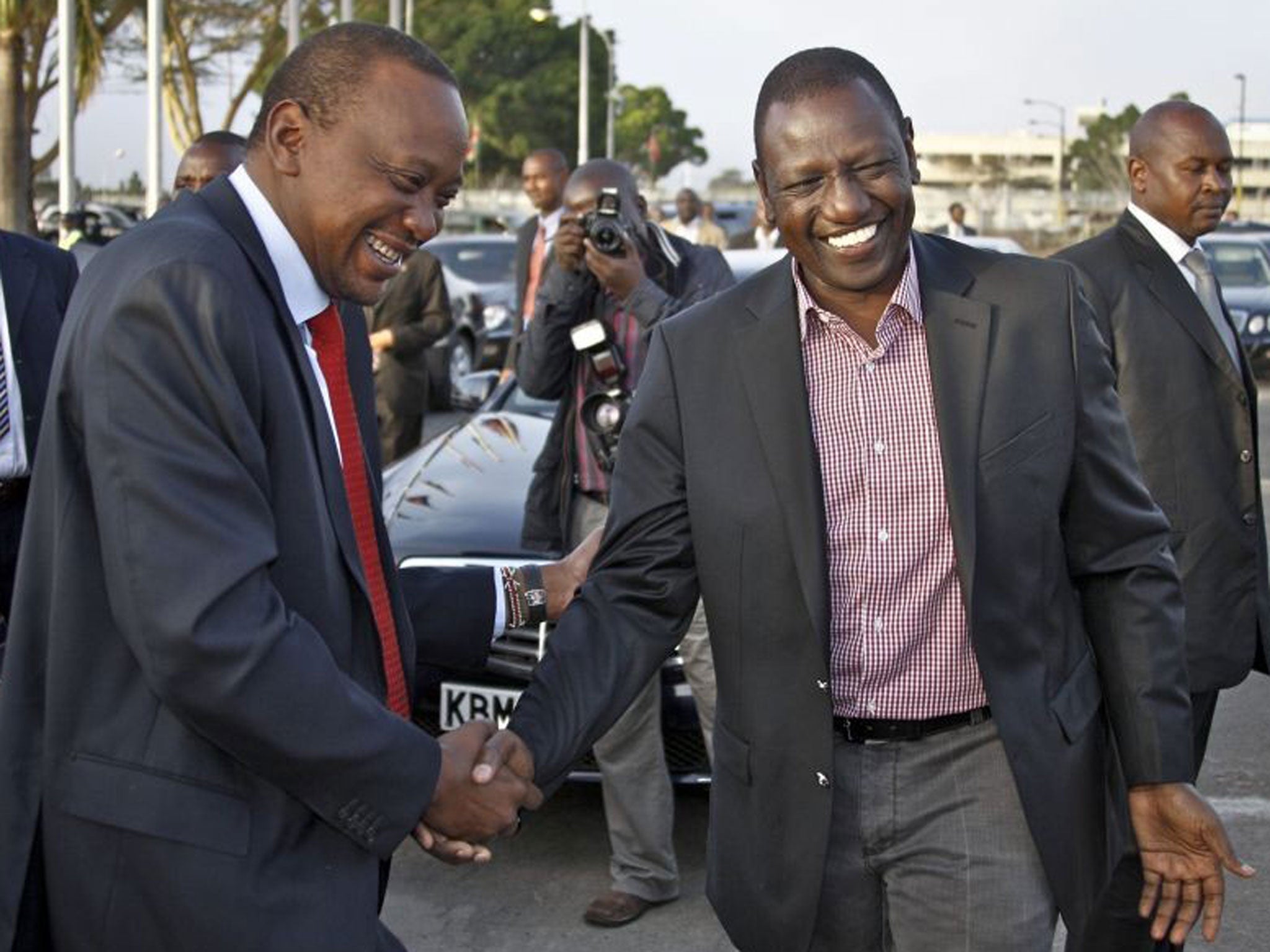

Your support makes all the difference.The African Union's executive council has condemned the International Criminal Court's charges against President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya as "totally unacceptable" and indicated that the continent's leaders could split from the body.

Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, both deny charges of crimes against humanity for orchestrating a killing spree after the country's disputed 2007 election which left more than 1,000 people dead and displaced more than half a million residents from their homes.

Speaking at a two-day African Union (AU) summit in Addis Ababa to discuss the continent's relationship with the International Criminal Court (ICC) yesterday, the Ethiopian Foreign Minister, Tedros Adhanom, announced African nations had agreed that sitting heads of state should not be put on trial by the ICC.

The ICC was described by Mr Adhanom as a "political instrument targeting Africa and Africans". He said it was "condescending" and rejected what he called the court's "double standard" in dispensing international justice.

"Far from promoting justice and reconciliation, and contributing to the advancement of peace and stability in our continent, the court has transformed itself into a political instrument targeting Africa and Africans," Tedros said. "This unfair and unjust treatment is totally unacceptable." Trying Kenya's Kenyatta and Ruto would infringe on the nation's sovereignty, he added.

Before this weekend's summit, senior figures in global politics urged delegates to reconsider threats to sever ties with the ICC in solidarity with Kenya.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu warned that leaving the ICC would be "a tragedy" for Africa, and that the continent had suffered the consequences of "unaccountable governance" for too long to disown the protections offered by the organisation. "Without its deterrence, countries could and would attack their neighbours, or minorities in their own countries, with impunity," he added.

Amnesty International said that leaving the ICC would be "reactionary in the extreme". Tawanda Hondora, the organisation's deputy director of law and policy said: "Such a resolution would serve no purpose except to shield from justice and to give succour to people suspected of committing some of the worst crimes known to humanity."

She added: "The ICC should expand its work outside Africa, but it does not mean that its eight current investigations in African countries are without basis. The victims of these crimes deserve justice."

But the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, said yesterday that this was not "a crusade against the ICC", but instead a "solemn call for the organisation to take Africa's concerns seriously".

The AU's council believes Kenyatta's trial will hinder Kenya's fight against terrorism, and proposed instead that Africans should deal with cases of genocide through an AU-backed court, and should not be forced to resort to the ICC in The Hague.

Some African leaders accuse the ICC of disproportionately targeting Africans. So far it has indicted only Africans, including Muammar Gaddafi's son, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, and Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, a guerrilla group which used to operate in Uganda. It has also issued a warrant for the arrest of the Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir over alleged genocide and war crimes in Darfur. It has sought the arrest of al-Bashir since 2011, and demanded that Malawi explain its failure to arrest Sudan's president when he visited the country that year. Malawi, where the entire cabinet of President Joyce Banda was sacked last week over a allegations of widespread corruption, said it was not its "business" to arrest al-Bashir.

To date, the only person to have been convicted by the court is Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, the DR Congo warlord who was found guilty of forcibly conscripting child soldiers to fight.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments