Academie francaise: who are the guardians of the French language?

In a world that is being reshaped by globalisation and social upheaval, can such an elitist institution survive, asks Adam Nossiter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Balzac tried and failed. Zola knocked on the door dozens of times and was always refused. Verlaine got no votes. Hugo got in, barely, only after multiple tries.

The august Academie francaise – the elite club of 40 “immortals”, as the members are known, that serves as the official guardian of the French language – does not admit just anybody. So exclusive is it that most of France’s greatest writers never made it.

But the sacred job of protecting France from “brainless Globish” and the “deadly snobbery of Anglo-American”, as a member spat out in a speech last month, has rarely been more difficult to attain.

Four vacancies – lifelong tenures – have opened since December 2016. Three times they have voted, most recently in late January, and three times they have failed to achieve a majority.

The deadlock, some academy members say, reflects France’s own – between the proud, timeless France determined to preserve itself at all costs, and the France struggling to adapt to a 21st century defined by globalisation, migration and social upheaval, witnessed in the “yellow vest” revolt.

“We’re the reflection of the society, and it’s a society that’s questioning itself,” says Amin Maalouf, the Lebanese-born novelist and a member of the academy.

Then there are those who grumble that, for a conservative institution rived by mutually hating factions, it is merely business as usual. The academy has been around since 1634, when it was founded by Cardinal Richelieu to promote and protect the French language, and it is not in any hurry.

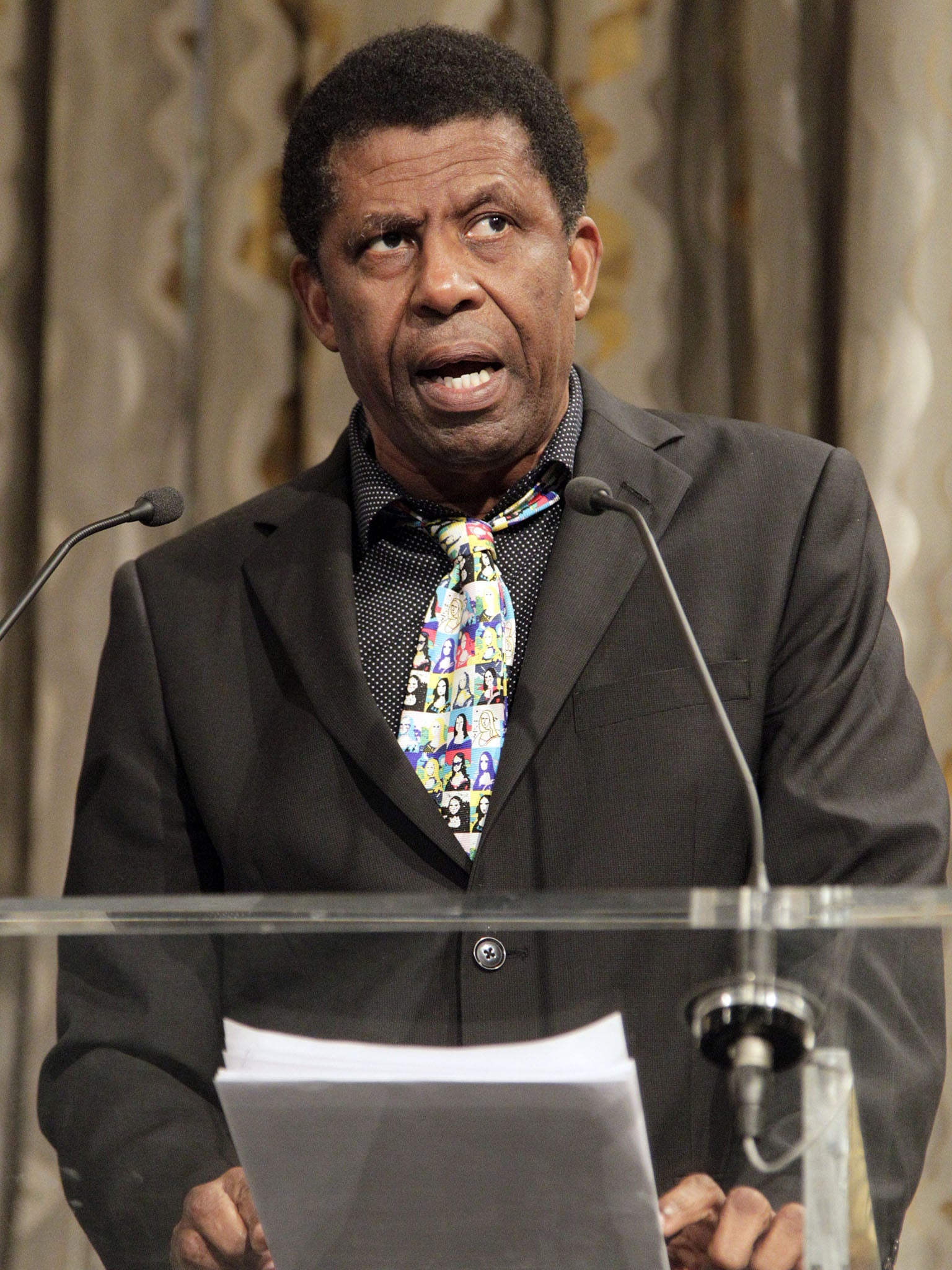

The academy “is an old lady, and very sensitive”, says one of the newer members, Haitian-born Canadian writer Dany Laferriere.

Actually, it is mostly old white men. There are just five women among the members, and Laferriere is the only person of colour. The average age was well over 70 in a recent tally by the French media.

Whether the academy is struggling to update or diversify itself, or even wants to, is difficult to divine. The deliberations of its members, under the graceful 17th-century dome of the Institut de France, are swathed in mystery.

But the rejections are humiliatingly public: former education minister Luc Ferry saw his name in the headlines recently, and not in a good way. The vote on his membership was decisive. Ferry declined to comment.

Aside from renewing itself, the academy’s real business is updating the definitive dictionary of French, which it has been doing since the 17th century. So sacred is the task that the updates are published as an official government document.

Earlier this month, the members approved the feminisation of professional titles. It was a veritable breakthrough for an academy that has for years resisted the adaptation, which is already practiced widely in France, with or without the sanction of the immortals.

Language may change, and society, too, but slowly in the view of the academy.

“The question is, should the academy guard its principles?” Laferriere says. “We could fill all the seats tomorrow.”

That is not likely to happen. The academy chooses you, you do not choose the academy. Nonetheless, no one can become a member without writing a strongly worded letter soliciting a place.

Some French writers never bother, as is rumoured to be the case with some of the country’s best-known contemporary authors.

Neither of France’s two living Nobel literature laureates, Patrick Modiano and Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, are members. Neither is Michel Houellebecq, reckoned to be among the most penetrating of all contemporary European novelists. Others are encouraged to apply, then lose the vote.

“We are alarmed at not finding academiciens that are to the taste of the academy,” Laferriere says.

But some members reject the argument that no upstanding defender of France’s language and cultural values can be found, and hint at a deeper crisis.

“It’s absurd,” growls Jean-Marie Rouart, a critic and novelist who has been a member since 1997.

The real question, for some, is what the deadlock says about the beleaguered France of today.

“What was special about France is that everybody recognised themselves in literature,” Rouart says. “Now, you’ve got to write for the university, or this group, or that group. It’s deplorable. People read more, yes, but what they read are idiocies. The academy is a boat adrift in a dry sea.”

Of the inability to move forward, Dominique Bona, a novelist and one of the few women to sit among the immortals, says, “I’m a little bit astonished.”

“We’ve had some remarkable candidates, real choices,” Bona says. “I’m personally disappointed that the academy is giving them the cold shoulder. Is this a French malaise? The bad mood around us, is it communicating itself to the academy?”

To be sure, the ceremonious world of the academy seems a universe away from France’s current yellow vest uprising, whose instincts tend more towards revolution than preservation.

In February, the academy members trooped down a wooden staircase of the Institut de France, the sharp drumbeats of the Republican Guard echoing through the marbled halls.

They were there to induct the newest member they could agree upon, novelist Patrick Grainville, an author of baroque fantasies.

Grainville took the seat of Alain Decaux, a journalist, historian and writer who died in March 2016. Generally, the academy waits a year after a death to announce a vacancy, and if a replacement receives a majority vote, a formal induction comes about a year later. Grainville was elected in March 2018.

Former president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, 93, a member of the academy since 2003, gamely negotiated the stairs supported by two aides. The smartly dressed invited public were scattered amid uniformed academy members, resplendent in their green embroidered uniforms.

Their custom-made robes cost in the region of £40,000, members said, and the swords that are de rigueur for members are not cheap, either.

The induction ceremony for Grainville spoke to an eternal France faithfully devoted to celebrating words and their ecstatic usage.

“Words shoot up like geysers from your pen, tumble in cascades, swirl about, bump into each other, are never at rest,” Bona said, describing Grainville’s work in the traditional induction speech. “You are, sir, a writer of jubilation.”

There was no hint of the social upheaval that has torn France apart in recent months. As with other ceremonious and antiquated French institutions, the pomp provides its own justification, even for those who harbour reservations about it. The academy for them represents France’s consecration of its writers, a nearly unique national status.

“It was the idea of getting on the magic merry-go-round,” says sharp-witted novelist Charles Dantzig, who was encouraged to apply after winning the academy’s prize, and then lost in recent balloting.

“It was the idea of protection,” he says of the appeal of being a member. “Illusory, no doubt.”

Indeed, the unusual nature of the academy’s mission, in a world where much of what it celebrates is under siege, leaves some members pessimistic it can protect even itself.

“French society: will it continue?” Rouart asks.

Then he answers his own question. “The bourgeoisie is dying,” he grumbles. Before, “you would see the academy members at dinner parties. Now there aren’t even dinner parties. It’s finished.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments