Why 2016 has been Chicago’s bloodiest year in almost two decades

By the end of November more than 700 people had been murdered in Chicago, mostly a result of gun violence that went beyond gang warfare

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a Friday afternoon in May, James, a softly spoken 19-year-old, had finished his shift making sandwiches at a branch of Jimmy John’s restaurant chain and was walking in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighbourhood when he heard four or five loud gunshots. “I looked,” James says, “and I see my ass bleed.”

He sprinted down State Street as one bullet pierced his arm and another flew past him and hit a woman walking out of Starbucks with her afternoon coffee. Yvonne Nelson was pronounced dead in hospital 40 minutes later. “She was a hard-working lady, a city worker,” says James, who asked me not to use his last name because he fears more attacks. “She lost her life for nothing.” Nelson died in a nice neighbourhood near the Chicago Police Department (CPD) headquarters, where the police superintendent had just announced the arrest of almost 100 gang members.

About a week after the shooting, James learned on Instagram that his would-be assassin was a 15-year-old affiliated with a gang called Murder Town. James was targeted because he used to run with a small crew associated with the Gangster Disciples, the city’s largest gang. “I did stuff in my past. I ain’t no perfect child,” he says. “He ain’t know me. Somebody sent him off. A little kid trying to earn some stripes.”

Nelson was the 238th person murdered in Chicago this year. By early March, experts worried the total number could reach 600 in 2016, a startling increase over any year in the past decade. But the pace of the killings accelerated, and by the end of November, there had been more than 700 murders in the city for the first time since 1998; that’s more than in New York City and Los Angeles combined. (Smaller cities such as New Orleans and Detroit have higher per capita murder rates.) The national murder rate, while historically low, is expected to increase by 13 percent this year – with almost half that increase attributable solely to Chicago, according to the Brennan Center.

Here, in the biggest city in the American heartland, teens murder each other over Twitter beefs, and grown men shoot children in the head – sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose. The carnage has even earned the city a grim nickname: Chiraq. As Chicago-raised rapper Kanye West says in his song “Murder to Excellence”: “I feel the pain in my city wherever I go/314 soldiers died in Iraq, 509 died in Chicago,” a reference to the death tolls of those places in 2008.

Roughly 90 per cent of this gun violence, police say, flows from gangs. And the rivalry that police say led to Nelson’s death reflects the changing nature of criminal organisations in Chicago. Massive gangs such as the Gangster Disciples and the Black Disciples used to operate with a corporate-like hierarchy and business planning, but aggressive federal prosecutions and the teardown of public housing splintered and scattered the gangs.

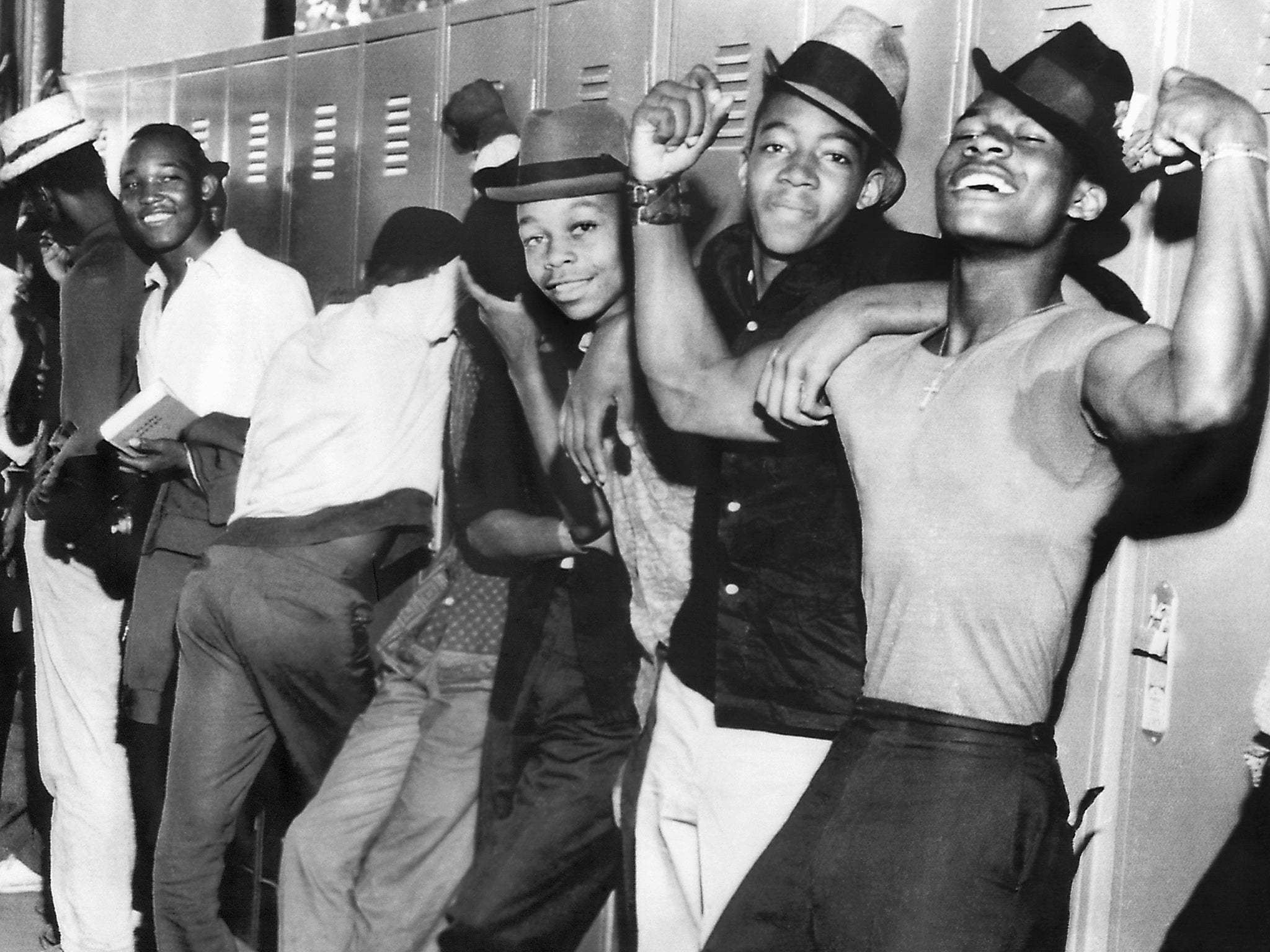

Chicago’s modern history of gang violence, especially on its West and South sides, goes back to the 1960s. (As bad as 2016 is, the total number of murders will still be well below the over 900 annual murders in the early 1990s.) But over the past year, two things have accelerated the attacks, according to social workers and law enforcement authorities. Budget cuts reduced the number of anti-violence social workers who once cooled the simmering feuds, and a series of deadly police shootings and alleged misconduct by police have torpedoed the relationship between police and residents.

Over the past 18 months, the drawdown of police and social workers has led to an explosion of violence not seen in almost 20 years – in August, 90 people were killed. It’s as if Chicago pulled its firefighters off a massive blaze and now residents are watching the flames engulf the entire city.

On a warm night in September, Alonzo Lee was sitting outside his family’s South Chicago home with his 3-year-old son, Akil, waiting for Alonzo’s father, Benny, to get home. Benny is a college instructor and respected social worker who teaches classes on the gangs of Chicago, but as a young man he was a feared leader with the powerful Vice Lords gang. Akil yells, “Main man!” as he runs to greet his grandfather, who scoops up the barefoot boy into his arms and quietly replies, “Hey, little rascal.”

Benny, a serious, soft-spoken man with broad shoulders, has a photo of the boy as the background on his phone. Alonzo says that when he was a child, Benny would tell him stories about gang life, cautioning him about how he and his childhood friends ended up in prison. But Alonzo still ended up joining No Limit, a renegade offshoot of the Black P Stones. Until November 2015, Alonzo says, he made $3,500 a day selling marijuana. Last autumn, police raided Benny’s house looking for Alonzo, who also got into a gunfight with a rival from a different set of his gang.

Alonzo says his father never glorified gang life and always tried to steer him away from it, but standing outside their home that night, Benny speaks warmly of his old life. “I had a lot of fun,” he says. “It was a lot of wrongdoing, but I had a lot of fun hustling back then.”

Benny was just entering his teens when his family moved into Austin in the mid-1960s, one of just three black families in the otherwise all-white West Side neighbourhood. “We had to band together to fight whites just to walk through the neighbourhood,” he says. “Just to get to the nearest swimming pool.” Grouping together with that small crew of boys from his block was his first step toward the gang life.

Large swathes of the West Side burned during the riots in 1968 that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Whites fled neighbourhoods in South and West Chicago, and as Austin became majority-black, large criminal organisations absorbed the small crews there. The Vice Lords, a sprawling West Side gang, took in Benny’s crew when he was 14. He and his clique carried guns for protection against other gangs and ran small-time hustles: robbing neighbourhood shops and jumping onto moving trucks to steal radios and televisions. But he wasn’t on the streets for long. A race riot at his high school got him sent to juvenile detention at age 15, and for the next 15 years, he split his time between the streets, where he was briefly the leader of the Insane Vice Lords, controlling about 2,000 gang members, and behind bars. He quit the Vice Lords for good when he left prison at 29 – “I told the ruling body that I was backing away,” he says – and later began a career in anti-violence social work that gave him an ongoing view into gang culture.

Benny says that back in his day and into the 1990s, when the gangs of Chicago had clear lines of authority, most of the violence involved turf squabbles and disputes over drug deals. If a gang member wanted to shoot a rival, he went to a leader for permission or risked punishment for attracting police attention that would endanger profit margins. And gang members honored a strict code against shooting children and bystanders. “When you had the gangs controlling the trafficking, the shootings were ordered,” Benny says. “It was business.”

Two events splintered Chicago’s large, organised gangs into the smaller crews that now shoot up the city’s streets. In the mid-1990s, federal prosecutions targeted and imprisoned leaders such as Gangster Disciple chief Larry Hoover. The other event began at roughly the same time, when the city’s troubled public housing was taken over by the federal government, which began plans to tear down the high-rises that had become a national symbol of urban blight. Over the next 15 years, the city demolished notoriously dangerous towers such as Cabrini-Green because of decrepit conditions and soaring crime. The unintended consequence: the gangs that had been largely contained in those buildings were now scattered like demon seeds in the wind.

In the early 2000s, about two decades after Benny left the Vice Lords, Alonzo began banging with the Bar None gang, a set affiliated with the Gangster Disciples. He joined for much the same reason his father did: to prevent getting jumped in his neighbourhood. “You kind of get that fear as a shortie that I can’t be that guy who gets beat up. I can’t be that guy who gets chased home,” Alonzo says. “If you don’t fight, you’ll be running your whole damn life.”

Back then, gang leaders – “big homies” – would intervene when younger gang members beat up a rival. “You’d get the older guys saying, ‘We don’t want this to be no war,’” Alonzo recalls. He adds that leaders would organise a fistfight between the victim and one of the attackers to forestall gunplay that would bring police attention to the neighbourhood.

But the old order was crumbling. Alonzo recounts what it was like when gang members from a demolished project moved into a neighbourhood of single-family homes.

“N****, I’m from the building,” a transplant would say, asserting his right to sell drugs near his new home.

“Well, I’m from these blocks,” the longtime neighbourhood resident would respond. “You can’t sell cocaine on this block.”

“Well s***, n****, I’m over here now,” the transplant would spit back. Alonzo growls like a rapper as he describes the landscape of project gang members spread across the city and the uncountable territorial skirmishes and shootings that followed as a result. “You either gonna kill me or what, I’m gonna keep getting money.”

In a dark and smoky South Loop studio, Rico Recklezz, a popular local rapper with dreadlocks and a tattoo of a machine gun on his stomach, leans into the microphone and growls out a verse. “Nowadays little n***** like to talk tough on YouTube and Twitter,” he spits. “Make me slide on you, hop out, walk up on your dumb ass and kill you.”

Recklezz – whose real name is Ronnie Ramsey – had family in the Black P Stone gang when he was young. At 10, he joined too, and by 14 he was carrying a gun. “He was a beast,” says Tray, a gang member in Englewood, a rough South Side neighbourhood. “He terrorised people.”

Recklezz, now 25, was a teenager when Chicago tore down its projects. Sitting on a recording studio couch while working on a joint the size of my ring finger, he explains how most gang members no longer have a leader issuing or enforcing rules. They operate in small crews of as few as a dozen members and open fire with no concern for who might catch a stray bullet.

In 2011, some bangers with a beef against Recklezz shot up his home and hit his mother and older sister. (Both survived.) “Hypothetically speaking, if I was a gang member and I was into it with somebody that did something to me, why would I care if there’s an old man outside?” Recklezz says. “That old man better duck.”

He says young men shoot each other over seemingly insignificant insults and conflicts. Violence that might seem gang related is often “just” personal. A 15-year-old Gangster Disciple named Speedy says that what sparks the most violence between gangs is “hoes”. Speaking over the phone in September, he scoffs at the idea of asking a higher-up for permission before attacking a rival and says there’s no real leader of his small GD crew, echoing what I heard from other young gang members. “Everybody’s on the same level,” says Speedy, who claims he’s been shot in the stomach and back. “If we want to shoot someone, we just pull up on them and start shooting.”

The insults that spark those shootings are often delivered on social media. Young men call out one another in long-winded threats in comment sections, and when they finally meet up face to face, there’s often nothing left to say; sometimes they start shooting immediately. “If they cut off all the social media sites, I ain’t gonna lie, it’ll stop some killing,” Recklezz says.

Just as young white American professionals post photos of themselves in Aspen or the Hamptons to show how fun and glamorous they are, poor Chicago teens post photos of themselves with guns and cash to show how hard they are. “Everyone playing so tough because of the internet,” Recklezz says. “That’s why they getting killed.”

Part of the reason young men are “playing so tough” is because, in very rare cases, the online posturing – combined with a real street reputation – can translate into millions. A handful of Chicago rappers, such as Chief Keef, a Black Disciple from Englewood, have become “drill music” stars, signed record deals and made enough money to start collecting art.

Recklezz is hoping to do the same. Back in the studio, he takes a call from a rapper who wants him to help him with a track. Recklezz tells him the price is $500 for a verse or $1,000 to appear in a video. “You can do Western Union or MoneyGram, whatever,” he tells the caller and hangs up.

He then turns to me and says, “I’m finna put my kids in a crib off this rap s***.”

Tray is standing on the street outside a drug house in Englewood. It operates with the permission of the local Gangster Disciple “big homie,” and the Gangster Disciples here call their territory “No Love City,” which is tagged in the stairwell of the Airbnb across the street. A steady stream of customers park their cars on the corner and walk up to the raised porch to hand money up to a slow-moving fat man. The fat man hands the money through a slitted window, receives contraband in return, then ambles back to lean over the porch railing and pass the drugs down to buyers in the alley.

“I’m doing work. Trying to see what these police up to,” says Tray, 19, peering down the block at a parked CPD SUV, the hood of his blue Yale sweatshirt pulled up over his dreadlocks.

Whenever Tray meets someone from outside his bleak neighbourhood, he asks them for a job. He became a Gangster Disciple in seventh grade because there wasn’t much food at home. He carried a gun for protection and earned money selling marijuana and Xanax, he says. As we talk, he’s sitting down the street from the drug house, on the stoop of the dilapidated house where he lives, where Cheetos bags and blunt wrappers litter the small yard and empty lots across the street mark where abandoned homes were torn down by the city. Lots of Chicago children and young teens join gangs for the same reason, he says: poverty.

It’s impossible to separate Chicago’s murder rate from its destitution, and its ugly legacy as one of the nation’s most segregated cities. The 16-block census tract where I stayed while reporting this story is 96 percent black and has a poverty rate of 46 percent, figures that are roughly the same in most of the Chicago neighbourhoods with high murder rates. There are few banks or grocery stores on these blocks, but many liquor stores and off-brand mobile phone shops.

“It’s hard to find and get a job,” says Dontell “DJ” Annan, another Gangster Disciple. “That’s what leads to the gangs and people hanging on the street and people holding guns.” He’s wearing dirty Crocs and a black tank top as we sit on a stoop across the street from the drug house Tray watches over. A silver hatchback speeds by the drug house, and DJ says driving fast is a good way to get your car shot up by wary gang members. “Now if we had some jobs, I don’t think none of this would be happening,” he adds.

A few days after Tray spotted the police SUV, I return to the drug house, but there’s no fat man on the porch and no customers parked on the corner or waiting in the alley. Tray, standing on the street again, says the drug house was selling to too many customers, so the big homie ordered it to be temporarily shut down. “Their door was going to get kicked in,” he explains.

He asks me to check him out online, where he’s posted slickly produced music videos of him rapping in expensive clothes in videos with titles like “Shooters Everywhere”. He has an impressive number of Twitter followers, but with the drug house shuttered, Tray has little to do today. Or tomorrow. “This is where I’m from,” he says, “so this is what I am.”

Police SUVs rolled by that Englewood drug house regularly, at least once an hour, when I visited it over five days in late September, and they are a common sight in other violent Chicago neighbourhoods. But I never saw the police stop a car or speak with anyone on the street. A veteran CPD detective – who asked that his name not be printed because he’s not allowed to speak with reporters – says that’s a shift from the more proactive policing the department once practiced.

Over an antipasti salad at an Italian restaurant in Little Italy (he’s trying to eat better), the detective says the current focus on police misconduct has kept police officers in their cars. He even advises officers under his command to make fewer stops to avoid encounters that could result in complaints or lawsuits. The feeling among Chicago police is that when a suspect resists arrest or pulls out a weapon and they respond with force, their commanders and the media won’t believe their account. He says they fear they’ll end up on the news or the target of lawsuits that will upend their lives and derail their careers.

Statistics back up his claim. The number of stops between January and late November dropped from about 560,000 in 2015 to 100,000 this year, a result of chastened police as well as a new agreement between the city and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) that changed the requirements and definition of a stop. Gun seizures are up 20 percent over the same period, to over 8,000 this year, though that figure includes firearms handed in at gun buybacks – a program the CPD stepped up in 2016. Chicago once had strict gun laws, but over the past six years, federal courts have struck down its handgun ban, ended Illinois’s concealed carry ban and forced the city to allow gun stores to open. Plus, smugglers bring in firearms from neighbouring states.

Whatever your feelings about the police, the withdrawal of a city’s police force can hurt the fight against violent crime, according to Zachary Fardon, the US attorney for the Northern District of Illinois. The current violence spike in Chicago followed four events late in 2015 that kneecapped residents’ confidence in police and officer morale, he said in a speech in late September.

First, in November, the city released graphic dashcam video of a white police officer fatally shooting Laquan McDonald, a black 17-year-old who was walking away from police when he was killed. After protesters and the City Council’s Black Caucus demanded the ouster of Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy, Mayor Rahm Emanuel fired him on 1 December. Less than a week later, the US Department of Justice announced it would investigate the department, focusing on its use of force and whether any racial groups bore the brunt of it. Finally, the agreement between the city and the ACLU, which also requires police to fill out lengthy contact cards every time they stop someone, went into effect on 1 January 2016.

“I also think that the fallout in public confidence – the apparent embattlement of police on all fronts – created a sense of emboldened aggressiveness among gang members, especially in Chicago’s most violence-afflicted neighbourhoods,” Fardon says. “Some gang members apparently felt they could get away with more, and so more bullets start[ed] flying.”

A news report that leaders from three West Side gangs had gathered to plot attacks on police officers was “complete bullshit”, the detective tells me as we eat our salads – there are no more “big bosses” who would hold such meetings. Still, the department did warn officers that gang members planned to target them, and officers reportedly responded by keeping a lower profile and stopping fewer people.

Recent research reveals another drawback to high-profile police misconduct. One study shows that after news reports about police assaults or shootings of innocent black men, calls to 911 and other crime reporting drop significantly, especially in black neighbourhoods.

While I was in Chicago, Emanuel announced the hiring of 970 officers, detectives and supervisors in a bid to lower the murder rate. When I asked the detective whether he thought the new police would help, he blew air through his lips to make a farting noise and gave a thumbs-down with his non-fork hand. “It would help if they got rid of this crap of ‘We’re always wrong’,” he says.

“They hop out on you less,” Tray says of the police bowing out of aggressive stops in his neighbourhood. The police still drive by and see young men selling drugs, but they don’t stop. They used to get out of their car the first time they passed by, Tray says. But now they’ll drive by twice without stopping, and only if the young men are still there on the third pass will they get out of their patrol cars.

“I tell them, ‘Be careful. Don’t be so aggressive out there. Think of your family before you go out there and do something,’” the detective says as he finishes his salad, laying out the advice he gives officers under his command. “Policing has changed. If you don’t change with it, you’re going to lose your job.”

It’s dusk, and the liquor store car park on the corner of East 79th Street and East End Avenue is crowded. Up to a dozen men, most in their late teens and early twenties, stand around talking and laughing and shadowboxing, smoking cigarettes as young women stop by to flirt and smoke. The parking area serves as an informal social club for people in the South Shore neighbourhood.

A small team of social workers – they call themselves violence interrupters – stand on the corner of the car park and eye the young men. “We had a homicide over there where those kids are playing,” says Ulysses Floyd, an ex-gang leader who now works as an interrupter for the nonprofit CeaseFire, the Illinois branch of the international program Cure Violence. “This is what we call a hotspot.” That’s why Floyd and a handful of other interrupters are standing on this corner in a Gangster Disciples neighbourhood at 7pm. on a Thursday evening – to cool the boiling tempers that erupt into gunfire and bodies on the sidewalk outlined in chalk. In the two hours I’m there, no police drive by.

The interrupters are here to form relationships with the men in the parking lot so that when conflict inevitably flares, they can step in and steer the young men toward solutions that don’t involve an ambulance. “Say some guys shoot over here right now. All the guys in the neighbourhood are going to go get guns,” says Chico Tillmon, a CeaseFire project manager whose gang past gives him credibility when he mediates conflicts. “I would come to speak to that group unarmed, knowing they have guns, knowing they are upset and knowing they are shooters.”

A Northwestern University study in 2009 found that CeaseFire decreased both overall shootings and retaliation killings among gang members. In 2014, a University of Illinois at Chicago study found that the program cut murders by 30 percent in the two police districts where the city funded its work. But in March 2015, a budget fight resulted in a freeze on state spending and a cut to social service programs, including CeaseFire, which had been operating in about 16 neighbourhoods. The organisation was able to keep its South Shore location open, however, and the interrupters from that office are here on East 79th Street this night.

There are few hopeful signs. Outside the liquor store, drunks beg for change, and inside mothers use food stamps to buy chips and juice for the toddlers trailing behind them. There is a memorial card for Jamel Rollins tucked beside the cash register. He was a 17-year-old kid from north-west Chicago who was shot and killed by two men in the empty car park that adjoins the store. The card unfolds to the size of a full piece of paper and is expensively printed with notes from his mother and siblings and praise for his sense of humor, his passion for rapping and video games and his love of dogs.

The photographs of Rollins show him throwing up gang signs. He holds up a sign insulting the Black Disciples in one photo, disses the Latin Dragons in another and calls out the Vice Lords in a third. When anyone who wants to remember Rollins pulls out that card, they’ll see the young man they loved celebrating the gang life that put him in the ground.

Back in the shadows on the darkened lawn in front of his family’s home in South Chicago, Alonzo scans the street for any signs of danger – just like Tray in front of the drug house and just like James when he leaves Jimmy John’s. Next to him, Benny does the same as he cradles Akil in his arms, protective of the little boy who will soon grow up and have to make his own way through the streets of Chicago.

Benny and Alonzo pay special attention to any cars on their street cruising slowly, or any ones they don’t recognise. “When I get out my car, I look in my rear-view mirror to make sure nobody coming up behind me,” Benny says. “Just ’cause I changed don’t mean the world’s changed.”

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments