In West Virginia, a moving, respectful tour of the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“If only these walls could talk!”

The thought occurs to me as I’m led down the long, gloomy corridors of the building known as the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum, which housed thousands of patients over its 130-year history as a hospital for people with mental illnesses and disabilities.

But after hearing about the horrors that took place here, including patients who endured severe overcrowding, were shackled to walls or were victims of abuse, I realise that perhaps it is better that the walls remain silent.

The asylum stands on a lush, 300-acre parcel of land in what now is Weston, West Virginia. The Virginia General Assembly authorised its construction in 1858, intending that it join its predecessors in Williamsburg and Staunton as the commonwealth’s third such institution.

The outbreak of the Civil War brought a diversion of funds and a delay in construction. When the asylum admitted its first patients in 1864, it was under the governance of West Virginia, which was admitted to the Union the year before, having begun the process of becoming a separate state in 1861.

The asylum housed patients until 1994, when it was replaced by the William R Sharpe Jr Hospital, also in Weston. The abandoned hospital remained shuttered for more than a decade and fell hard into a state of neglect and disrepair.

West Virginia businessman Joe Jordan and his family purchased the former asylum at auction in 2007, with the intention of preserving and restoring it. The facility was opened to the public later that year, sparking complaints about the use of the pejorative term “lunatic” in the name, and the controversial titles of such events as the “Psycho Path” and “Lobotomy Flashlight Tour”.

In news accounts at that time, mental health advocates criticised the facility for exploiting people with mental illness and denigrating the field of psychology.

A spokeswoman for the asylum said that, although the facility went by several names over the years, the name Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum was chosen simply because it was the facility’s original name.

The facility now offers a variety of tours and experiences, including paranormal tours, 45- and 90-minute heritage tours, photography tours, ghost hunts and tours of the facility’s farm, cemeteries and wards for the “criminally insane”. The year-long calendar of events features such diverse affairs as a drag show, barbecue championship, car show and haunted house, and the annual Asylum Ball.

Although the “Psycho Path” and “Zombie Flashlight Tour” have been discontinued, the asylum’s calendar still includes special events with questionable names and themes, such as “Crazy for Barbecue” and “Zombie Paintball,” and the ghost tours spin tales of patients who lived – and died – there.

I arrive for my tour of the asylum on a sunny but chilly day in early April, soon after the beginning of the spring tour season. I prefer my history straight up – no lost souls, disembodied voices or self-propelled objects – so I opt for the 90-minute heritage tour, which covers all four floors of the main hospital building and the first floor of the medical centre.

While waiting for the tour to start, I watch a short film about the history of the asylum and browse through two front rooms that feature photos and displays commemorating the lives and works of Dorothea Dix and Thomas Story Kirkbride, 19th-century advocates for treating mentally ill people with dignity.

Dix was a social reformer whose tireless efforts led to the establishment of the nation’s first public hospitals for people with mental illnesses and disabilities.

Kirkbride, a physician, pioneered the construction of asylums designed to promote healing and recovery, emphasising the restorative properties of natural sunlight and beautifully landscaped grounds. His ideas influenced the design and construction of hundreds of such facilities, including St Elizabeths Hospital in the District of Columbia as well as the asylum in Weston.

At the appointed time, a small group gathers inside the hospital’s main entrance, where we are greeted by Lowther, our guide, who is dressed in an old-style nurse’s uniform. At the outset, she addresses the issue of the facility’s name.

“Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum” was the name given to the hospital by the Virginia General Assembly when it was established in 1858, she says. When West Virginia assumed control of the asylum in 1863, its name changed to the West Virginia Hospital for the Insane. By the early 1900s, it was known simply as Weston State Hospital, which Lowther acknowledges is more “politically correct”.

As she leads us around the exterior of the main building, I’m reminded of a line from “Mrs. Robinson” by Simon & Garfunkel: “Stroll around the grounds until you feel at home.”

The setting is beautiful, and the hospital’s exterior is stunning. The facility is aptly described on its Facebook page as appearing “more European castle than American hospital,” with an “imposing Gothic structure that exemplifies Victorian architecture at its finest.”

The building, designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1990, is indeed massively impressive. It spans nearly a quarter of a mile from end to end – 1,295 feet to be exact. Lowther informs us that the interior contains more than nine acres of floor space, with several wings extending from the building’s central area. It is, she says, the second largest hand-cut sandstone building in the world. (The largest is the Kremlin.)

Lowther points out the athletic field on the front lawn, still equipped with a backstop where soldiers played baseball during the Civil War. Over the years, children from the town were allowed to play baseball and football there.

To one side is a hill, where three cemeteries serve as the final resting place for patients whose families never reclaimed their bodies – often because of the stigma associated with mental illness, Lowther says.

Greenhouses and a dairy barn were among the outbuildings that provided work for some of the patients. Whenever possible, they were given tasks that would give them a sense of accomplishment and reduce the need for paid staff, she says.

When the tour moves inside, Lowther warns that it will be colder because we won’t feel the sunshine anymore. She’s right. The facility has only been partially restored, and the interior is cold in the winter and hot in the summer. The long, dark corridors are flanked by walls with badly peeling paint, and water pools on the floors of some of the rooms.

The tour moves quickly through rooms that once served as the kitchen, dining areas, employee break room, morgue and geriatric men’s ward. We pass the dentist’s office, barber shop and beauty parlour. The Old Soldiers’ Ward once housed World War I veterans suffering from what was then known as shell shock – a term that has been replaced by post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

Lowther shows us the apothecary, where heroin, cannabis and bourbon were among the “medicines” that were dispensed to treat the patients.

A cross is displayed in the window of a large, empty auditorium, indicating that the room was once used as a chapel. The auditorium served multiple purposes, such as an athletic court, where boys from the town would play basketball against teams of patients. The local high school even held its proms there, Lowther says.

The upper floors include living areas for the patients, doctors and nurses. We pass a room that has been featured on television programs that focus on ghosts and the paranormal. Lowther says it is reputed to be one of the hospital’s most haunted rooms, where she swears that she once saw a ball move by itself – a good teaser for one of the asylum’s ghost tours.

As Lowther leads us through the wings where the patients lived, it becomes apparent that the hospital is a study in contrasts and contradictions. It was conceived and constructed with good intentions and high ideals – respect for the dignity of each individual, with bright, airy living spaces, nicely decorated common areas, high-quality food service and an open campus – all of which were intended to promote healing and recovery.

The hospital was originally designed as a residence for 250 patients. Most would have a tiny, private room with a small bed and a window to let in natural daylight and provide a scenic view.

But the grim reality fell far short of those lofty ambitions.

Over time, the hospital became badly overcrowded, housing more than 2,600 patients at its peak occupancy in the 1950s, Lowther says. She tells us that the rooms and corridors were crammed with as many beds as they could hold. When the overcrowding was most severe, the same beds were used by multiple patients, sleeping in shifts.

One wing displays photos depicting some of the most controversial treatments that were used over the years: insulin-shock therapy, in which patients were placed in medically induced comas, ice-cold hydrotherapy to treat women diagnosed with hysteria, and “ice pick lobotomies”.

The notorious lobotomies, which doctors performed for decades in the mid-20th century, involved the insertion of an instrument resembling an ice pick through patients’ eye sockets to sever connections in their brains, usually destroying their personality as a result. The Weston facility was one where Walter Freeman, known as the “father of the lobotomy”, performed the controversial procedures, Lowther says.

Before the tour ends, she stops to talk about why people were committed to the asylum. It wasn’t always because of mental illness. They might have had physical ailments such as asthma, epilepsy, rabies or tuberculosis. Some had suffered brain damage from being kicked by a horse.

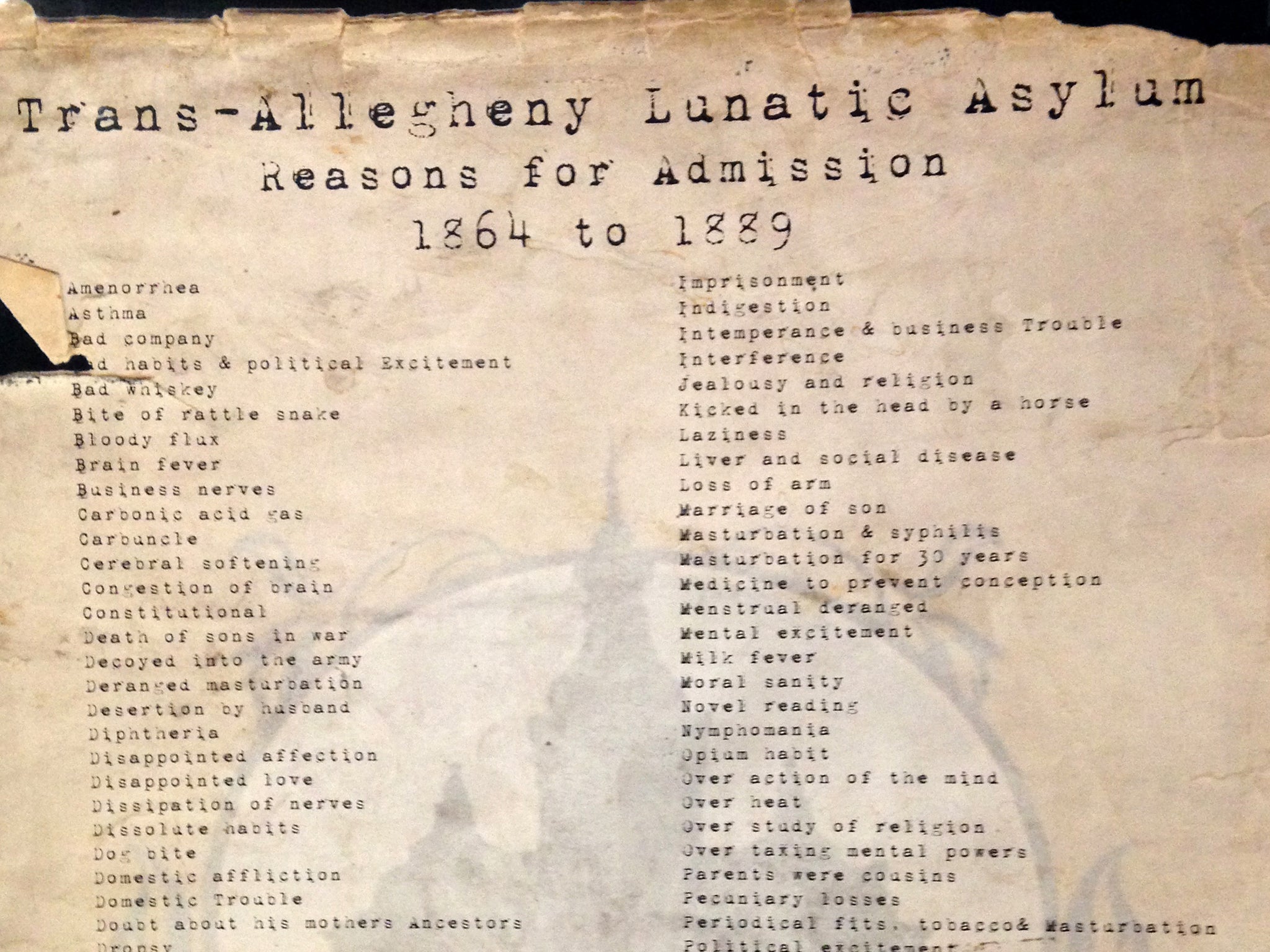

The asylum’s gift shop displays a poster – an enlargement of a document compiled from patient case studies listing some of the factors that led patients to be admitted to the asylum between 1864 and 1889. It includes such curious entries as “vicious vices in early life”, “seduction”, “egotism”, “bad whisky”, “indigestion”, “loss of arm”, “shooting of daughter” and “doubt about his mother’s ancestors”.

In the 1800s, when women had few rights, it was easy for men to have their wives committed for the rest of their lives, she says, suggesting that this could have been a way for the men to get their wives out of the way so they could pursue new relationships.This might explain some of the entries documenting some of the underlying reasons behind hospital admissions: “change of life”, “menstrual problems” and “childbirth”, as well as political or religious “excitement”, “disappointed love”, “death of sons in war”, “domestic trouble”, “laziness” or “novel reading”.

The tour provides a fascinating look at the asylum and a glimpse into the lives of the people who resided and worked there. Despite my misgivings about the use of the term “lunatic” in the facility’s moniker, and the names of some of the events, I feel that the heritage tour has generally been tastefully conducted and respectful of those who received care there.

When the tour ends, I study the poster in the gift shop and wonder about the patients – what their lives had been like before they arrived there and the reasons they were institutionalised, as well as their experiences inside.

The asylum does not have medical records of the patients who were admitted there, and I understand why their names or images are omitted from the tour. But the asylum’s story is ultimately about people, and although the tour has left me wanting to know more about them, their secrets will never see the light of day.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments