After the tragic death of Harambe at Cincinnati Zoo, it’s easy to forget the story of escape artist Ken Allen

They shoot you in the wild, they shoot you in the zoo. It’s hard being an ape in 2016. But, says Joe Veix, it wasn’t always so tough

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last month, headlines mourned the death of Harambe, the gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo shot to death when he started dragging around a three year-old boy who had fallen into his enclosure. Contrast that to 13 June 1985, when a 250-pound orangutan named Ken Allen climbed up his retaining wall at the San Diego Zoo and escaped his pen.

He walked down a public path toward crowds of tourists, stopping to look at the other animals as if he were a visitor before being led back to his cage. It would not be the last time he escaped, but instead of a PR disaster, for a brief time in San Diego, Ken Allen became a folk hero. After that first escape, zoo officials ramped up security in the pen – an open area with a jungle gym made of utility poles and a large moat at the back. Behind the moat was a massive wall, which they extended four feet – but it wasn’t enough to contain Ken Allen.

A few weeks later, in July, he managed to climb the wall again. This time, he was a bit more irritable. Zookeepers found him in front of another ape enclosure, tossing rocks at Otis, a fellow orang-utan and former pen-mate who, according to the Los Angeles Times, was “not known to be amiable”.

The escapes continued. That August, Ken Allen found a crowbar in his pen that workers had left behind. He tossed it to another orang-utan, Vicki, who used it to pry open a window and let Ken out. After that incident, he was moved temporarily to an indoor pen with “a black-and-white television with one working channel”, according to the Times, while zookeepers increased the security of his original pen.

They probably should have seen his knack for escaping earlier. Born in captivity, Ken Allen got his name from the two keepers, Ken Willingham and Ben Allen, who rescued him from his also-captive mother after she attempted to smother him. As an adolescent, he would regularly unscrew the bolts of his cage and explore his nursery at night, returning in the morning and putting it back together before his keepers arrived.

Reports of his quest for freedom – especially in the 1980s, an era known for its schmaltzy patriotism – became a major selling point for the zoo. It began printing T-shirts featuring all of the headlines written about Allen and sold them for $14 (£10). “Free Ken Allen” bumper stickers were printed. One newspaper article described him as “Hairy Houdini,” a nickname that stuck.

Ken Allen even had a fan club, consisting mostly of pensioners who called themselves the Orang Gang. One member, a lab assistant named Twyla Baker, printed a 100-subscriber newsletter called The Orang Gang News.

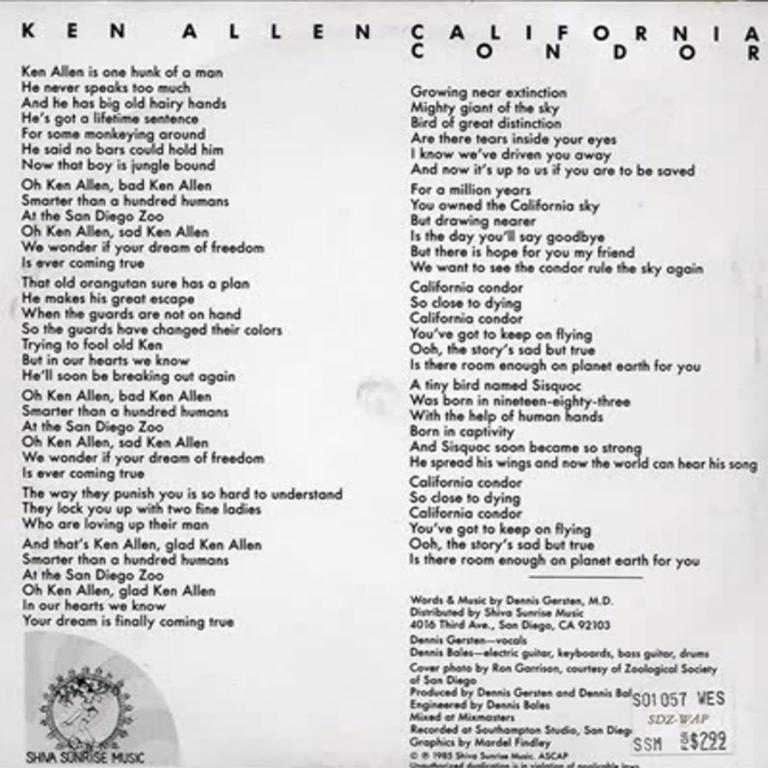

It gets weirder. A San Diego–based psychiatrist called Dennis Gersten was so inspired by Ken Allen that he wrote a song about him. (Sample lyrics include “Ken Allen is one hunk of a man/Never speaks too much/He has big ol’ hairy hands/He’s got a lifetime sentence for some monkeying around/He said no bars can hold him/Now that boy is jungle-bound.”) The song became an instant local hit, and a single was sold at the zoo for several years.

Meanwhile, zookeepers struggled to contain Ken Allen. They surrounded the moat’s wall with electric wire and hired rock climbers to look for potential escape routes. Once the orangutan learned not to try anything around uniformed zoo employees, they went undercover, disguising themselves as tourists – what one headline dubbed “gorilla tactics.”

Eventually, the zoo spies caught him climbing “like Spiderman” up the exterior wall, before brushing the electric wire and giving up. The new security measures seemed to work. According to one report, Ken Allen “settled down as a ‘family man’”. But that was only a ruse. Two years later, he escaped again. This time, his enclosure’s water pump clogged, causing the moat to dry up. Before anyone noticed, according to a Los Angeles Times article, he “walked across the dry moat and hoisted himself onto rocks outside the enclosure.”

Once again, he wandered around the zoo, posing for photos with tourists. A zoo gardener spotted him and cleared the area. As security guards converged on him, guns ready, Ken Allen bolted, heading toward the lion pens. Before he reached them, vets managed to corral him back to his enclosure, “nervous and agitated”, but unharmed. It was the furthest from his enclosure he’d ever got.

Desperate, zookeepers added female orangutans to his pen, thinking they could distract him. But Ken Allen was a bad influence on his new friends. A few months later, two of them, Jane and Kumang, found a five-foot-long squeegee left behind by window washers and used it to climb up the wall. Jane was found walking on the path near the flamingo exhibit and was tranquilised, while Kumang was peacefully returned to her pen.

The zoo spent roughly $45,000 on new security measures, and the escapes finally stopped. Ultimately, there were nine total breakouts, according to the Lodi News-Sentinel, “with crowds cheering the apes on as keepers ran after them.” The local news kept up with him for a few more years, but the coverage gradually faded, and Ken Allen returned to a simple life of sitting in his pen and giving young children the finger.

In the winter of 2000, he began acting erratically and was diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma. The Orang Gang News published a special, two-page tribute edition and held a candlelit vigil for him. Retired postal employee and Orang Gang member Marlene MacLeay told the Los Angeles Times, “He’d have done the same for us.”

With little hope of survival, Ken Allen was euthanised and cremated on 1 December 2000 at the age 29. Or was he? Perhaps Ken Allen faked his death in an elaborate, final escape, and is laying low across the border in Mexico. And maybe one day he’ll return.

© Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments