13 unusual coronation customs from gold ingots to the threat of a duel

Celebrations over the years have featured secret recipes, a pardon for criminals and a royal stay in the Tower of London.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The intricate coronation ceremony and its celebrations comprise a host of curious customs.

Here are a few of the unusual rituals past and present which have featured in the historic occasions.

A night in the Tower of London

For hundreds of years the monarch stayed at the Tower of London two nights before the coronation.

Preparations included the creation of the Knights of the Bath – the monarch’s special escort for the coronation.

A chosen selection of young squires were ritually bathed – symbolising their spiritual purification – before spending the night in prayer.

The next day they were “dubbed” – knighted – by the monarch before escorting the sovereign in their procession from the Tower.

The monarch made their way through the City of London to Westminster the day before the coronation, seeing a series of pageants set on elaborate stages as part of the journey.

The last coronation procession from the Tower of London was Charles II’s in 1661.

Secret recipe for holy oil

The exact recipe for the oil used for the anointing of a monarch is kept a closely guarded secret.

It is usually made by the Surgeon-Apothecary and consecrated by a Bishop, with a large enough batch mixed to last a few coronations.

In 1941, during the Second World War, a bomb hit the Dean’s Study in Westminster Abbey destroying the remaining oil.

A new batch had to made from scratch for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953.

Charles III’s holy oil was made sacred in Jerusalem, and consecrated by the Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Anglican Archbishop in Jerusalem.

It was created using olives harvested from two groves on the Mount of Olives and pressed just outside Bethlehem, and perfumed with sesame, rose, jasmine, cinnamon, neroli, benzoin, amber and orange blossom.

The oil is vegan-friendly, whereas the oil used to anoint Elizabeth II came from a musk deer, a civet cat and a sperm whale.

The King’s Champion

The office of King’s Champion began in the reign of William the Conqueror.

It was the Champion’s duty to ride, on a white charger, fully clad in armour, into Westminster Hall during the coronation banquet.

His role was to defend the monarch’s honour and challenge any person who dared to deny the sovereign’s right to the throne to a duel.

Queen Victoria dispensed with traditional ride and challenge custom at her coronation, and Henry Dymoke – Queen’s Champion at the time – was made a baronet by way of compensation.

A member of the Dymoke family carried the Royal Standard at Elizabeth II’s coronation.

Francis Dymoke, a former accountant and the 34th generation of the family to run the Scrivelsby country estate in Lincolnshire, is the current champion, but is not expected to be taking to a horse for the proceedings nor demanding any duels.

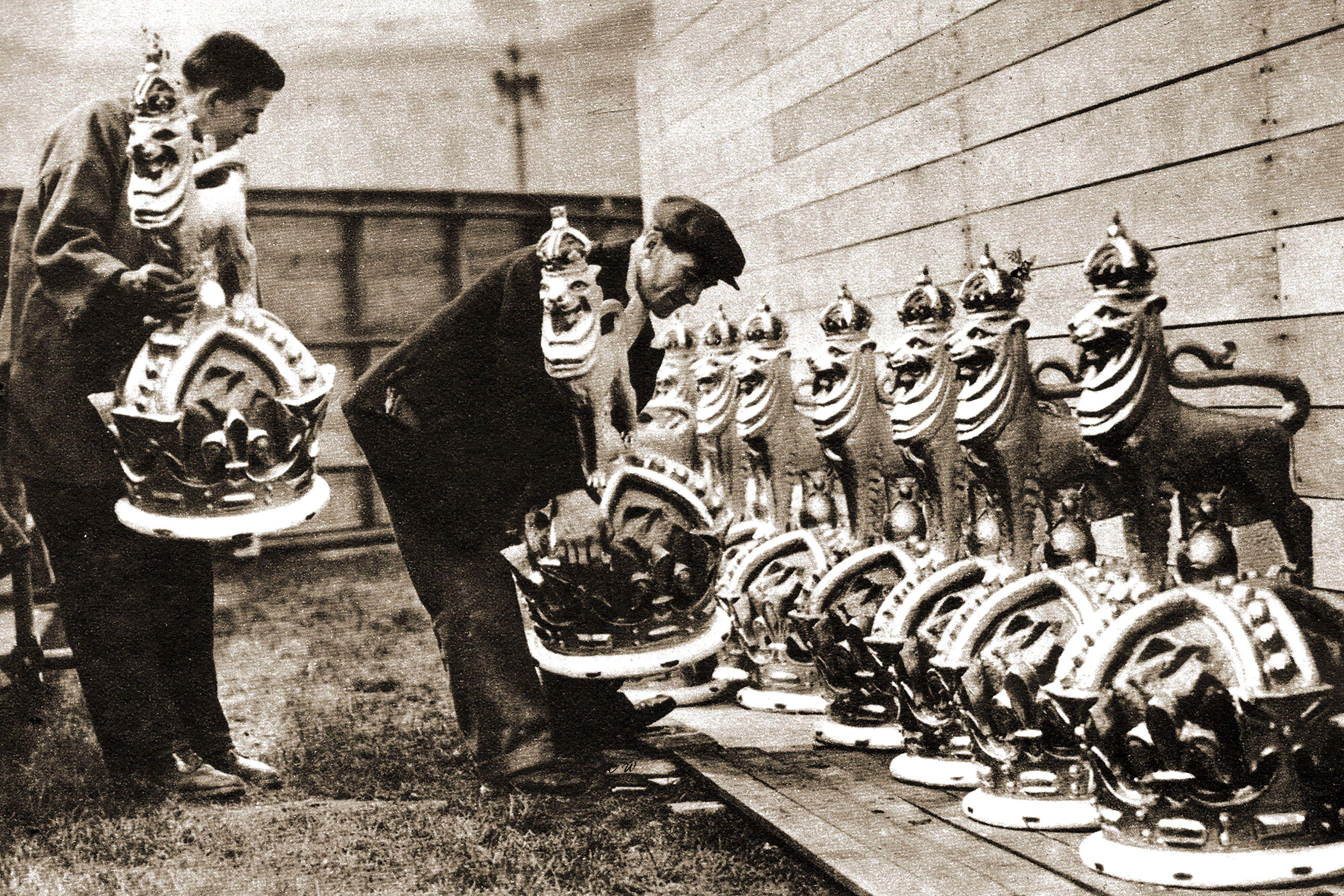

Sale of coronation furniture

Throughout 20th century coronations, it was customary for chairs and stools to be specially designed for those attending and to include the royal cypher.

After the ceremony, the new Abbey furniture was sold, with preference given to those who had occupied the seats, and the rest auctioned, with the money going towards the cost of the coronation.

In 1953, applications could also be made to buy the carpets which covered the floor of the Abbey and for the damask frontals, with preference given to churches.

The hidden anointing

Because the anointing of a monarch with holy oil is the most sacred part of the ceremony, no-one sees it apart from the sovereign and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The King, according to tradition, will be hidden beneath a golden canopy held over his head as he is consecrated – with the anointing signalling that he has been chosen by God.

Ingots

According to tradition, a monarch offers an ingot – or wedge – of gold of a pound in weight (around 450g) – worth about £18,500 for a troy pound – at the High Altar before their communion.

It is delivered to the monarch by the Lord Great Chamberlain and carried to the altar by the Archbishop of Canterbury in an embroidered velvet bag on a tray as an offering from the sovereign.

A Queen Consort traditionally offers a mark weight of gold – which is eight troy ounces (250g) – and worth around £12,500.

There have been suggestions Charles will dispense with the ritual of offering ingots at his own coronation.

Handel’s coronation anthem

The dramatic, stirring Zadok The Priest has been sung at coronations in England for more than 1,000 years.

Handel composed the current musical setting for the coronation of King George II in 1727.

It is sung just before the anointing as the monarch is divested of their robe and takes their seat in the Coronation Chair for the first time.

The Stone under the Chair

Beneath the Coronation Chair will be the Stone of Destiny, also known as the Stone of Scone.

The ancient symbol of Scotland’s monarchy – a large rectangular block of sandstone weighing more than 150kg – was seized by Edward I of England in 1296 and not officially returned to the Scots until 700 years later.

Edward I commissioned the Coronation Chair to house the stone and, since the 13th century, all English and later British sovereigns have been crowned while seated above it.

It now leaves Scotland only for coronations.

According to Scottish myth, the stone was brought to Scotland by Pharoah’s daughter Scota.

In the English version, it was the stone on which the patriarch Jacob had laid his head at Bethel and dreamed of a ladder of angels stretching from earth to heaven.

Monarchs stay at home

It is rare for foreign monarchs to attend the coronation of a British King or Queen, according to the House of Commons Library.

In 1953, the ceremony was attended mostly by crown princes or princesses – although the Queen of Tonga and a number of sultans were there.

Prince Albert II, ruler of Monaco, has, however, said he will attend Charles’s coronation, as have King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima of the Netherlands – suggesting a break with tradition in 2023.

One hundred shillings for a sword

During the service, one of the peers traditionally offers the price of 100 silver shillings for the jewelled Sword of Offering in its scabbard to symbolically redeem it.

The shillings are delivered to the altar in a golden basin as part of a 650-year-old custom.

The peer then draws the sword and carries it in its “naked” form – without its scabbard – before the monarch for the rest of the service.

The intricate tapered sword, which was made for George IV’s coronation in 1821, is decorated in roses, thistles, shamrocks, with its hilt encrusted with diamonds, rubies and emeralds.

Blood princes and peers

The Archbishop of Canterbury pays homage to the monarch, followed by the senior peers, with the Prince of Wales and other blood princes taking precedence.

There has been a suggestion William will be the only blood prince to do so at the King’s coronation, which would remove the problem as to whether the disgraced Duke of York and controversial Duke of Sussex would be called upon to take part.

It has also been suggested that the King will cut the homage of other peers – dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons – from his ceremony to save time.

The ritual involves the peer placing their hands between the King’s and swearing allegiance, touching the crown and kissing the King’s left cheek.

MPs never pay homage at a coronation ceremony.

Amnesty

It used to be customary for a general pardon for criminals to be proclaimed during the service and read out by the Lord Chancellor.

This has been abandoned, but the Queen, ahead of her coronation in 1953, declared an amnesty for war-time deserters.

Court of Claims

Under a 650-year-old tradition, anyone whose ancestor played a role in a previous coronation can apply for a part in the May 6 ceremony.

The Cabinet Office set up a special Coronation Claims Office to look into the ancient ritual of the hereditary right, with a deadline of just four weeks to apply.

Thirteen successful applicants have been announced so far including the Earl of Erroll, who will bear a silver baton as Lord High Constable of Scotland, and the Earl of Loudoun, who lives in Australia and applied to carry the Golden Spurs like his ancestors.

The first recorded use of the Court of Claims was in 1377, when John of Gaunt, the uncle to a 10-year old Richard II, decided who would carry out which task during the boy-king’s coronation.