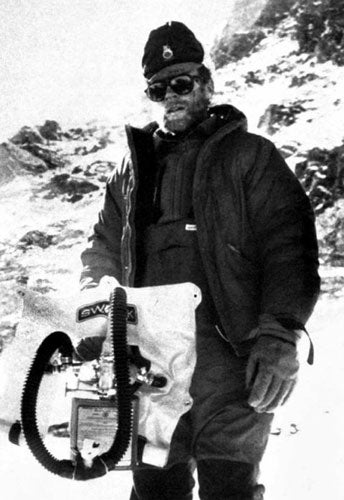

The History Man: The tale of Tom Bourdillon

Tom Bourdillon came within 300ft of immortality as the first man to climb Everest. Now fame beckons thanks to the breathing technology he pioneered, which could transform climbing and medicine, writes Andy McSmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tom Bourdillon came so close to being a household name. He was just 300ft away but to have crossed that distance would probably have meant death for him and his fellow-climber Charles Evans. So they turned back.

Three days later, Edmund Hillary and sherpa Tenzing Norgay succeeded where they had failed – they reached Earth's highest point, the peak of Mount Everest, and claimed immortality.

Bourdillon did not live long enough to make another attempt. After his tragic, early death, his name lived on in the mountaineering community, but for the public, he passed into obscurity. Only now, more than 50 years later, he has the chance of being honoured again – as a scientist.

When he was not tackling the world's peaks, Bourdillon worked for the British government as one of the pioneers of rocket design. As a sideline he designed equipment to help mountaineers breathe at high altitudes. It was his passion. He was convinced the apparatus in use was inefficient. It blew oxygen from a cylinder across the mountaineer's face to supplement open air, which meant some oxygen escaped.

It would be better, he believed, to clamp a mask over the mountaineer's mouth so no oxygen escaped, and have a second cylinder into which the mountaineer breathed out, filled with soda lime to absorb carbon dioxide.

Late in 1952, Bourdillon received a grant so he and his father Robert, a medical researcher, could design a closed cylinder system, which they hurriedly built in a lab at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury, and then whisked off to Snowdonia for tests.

Soon after, a team of British climbers led by John Hunt, and including Bourdillon and Edmund Hillary, set off to conquer Everest. Bourdillon and Evans, a brain surgeon, used the new closed circuit apparatus. Hillary and Tensing stuck with the usual open apparatus. Despite their heavy breathing equipment, the rocket scientist and the brain surgeon scaled most of Everest at record speed, covering the stage between 25,800ft and 27,300ft in 90 minutes. The same stretch took Hillary and Tenzing more than two hours.

But at that very high altitude, as the temperature fell, Evans' breathing equipment was giving him problems, and Bourdillon risked frostbite in his hands by adjusting it. They reached the final camp struck in 1952 by a Swiss expedition, and having rested, set off to altitudes higher than any European had ever reached.

Arriving at a sheltered area at 11am, on 26 May 1953, they decided to change the breathing canisters to ensure they had enough oxygen to reach the top. Ten minutes later, Charles Evans was in serious difficulties. He needed to take six breaths for every step.

At 1pm, they emerged on to Everest's south summit, at 28,740 feet, just 300ft from their destination, but it had taken them an hour longer than expected. Bourdillon, approaching exhaustion, took a hard look at Evans, and knew they had to turn back.

"The two men were an awe-inspiring sight," wrote Sir John Hunt, the expedition leader, who watched them struggle back exhausted to camp. "With their great loads of oxygen on their backs and masks on their faces, they looked like figures from another world. From head to foot they were encased in ice."

Mike Westmacott, 83, an old friend of Boudillon from Oxford University days, is one of only two members of that eight-man team still alive, 55 years later.

"I must say that all the rest of us on that expedition were very glad they did not go on," he said.

"It would have taken them at least a couple more hours, and when Tom got back he was exhausted. He might have got to the summit, but I don't think he would have survived."

Bourdillon's failure had lasting implications, because to this day, the only breathing kits for mountaineers are open circuit. But his son, Simon Bourdillon, is convinced it was bad luck and lack of time which led the kit to fail. "Dad came back from the Himalayas in August 1952, and was of the opinion that the closed circuit was the way to go," he said.

"He and my grandfather set about the design and development almost straight away. The funding did not come through until November 1952. The expedition left Britain in February 1953. So it was a very accelerated piece of development. It was effectively developed in three months from the the receipt of the funds.

"Dad tested it in North Wales, but it had never been developed to a stage of maturity until that expedition. He said it was good enough to get them to the top, but they used it unintelligently."

But in the 1950s, the lesson seemed clear enough – Bourdillon and Evans used closed circuit oxygen, which let them down as the temperature dropped to -25C; Hillary and Tenzing used open circuits all the way.

All further interest in Bourdillon's idea seemed to have died with him – until five years ago, when Dr Jeremy Windsor, part of a team at University College London studying medical techniques in extreme environments, wrote a paper pointing out that Bourdillon's equipment had allowed him and his partner to ascend more than 26,000ft very quickly. "Combining recent advances in breathing circuit technology with decades-old wisdom about closed-circuit oxygen systems, it may be possible to transform the way mountaineers travel at high altitude," he said.

The article was spotted by Dr Roger McMorrow, an Irish anaesthetist who, like Dr Windsor, is part of the Cauldwell Xtreme Everest project – a group of medics who went to Everest last year and set up the world's highest laboratory at 26,000ft. They worked on developing a new version of Bourdillon's equipment and used it on the expedition. But caution made them switch to open systems when at their second camp at 20,000ft.

Dr McMorrow is convinced it is possible to produce a modern version of Bourdillon's equipment that would work at the highest altitudes. "With an open circuit, an awful lot of oxygen is wasted and it becomes less efficient the faster you breathe. A closed circuit can deliver higher than sea level amounts of oxygen at high altitudes," he said.

He is also working with the private research firm, Smiths Medical, the medical arm of the giant Smiths Group, on a miniaturised system for sufferers of the increasingly-common disease, COPD, which restricts breathing, making it hard for sufferers to go out because they must be near to an oxygen source. The equipment could return their mobility.

The setback on Everest did nothing to dampen Tom Bourdillon's love of climbing. His friend Mike Westmacott went rock climbing with him shortly before his death. "Tom had something wrong with one of his hands," he recalls. "It wasn't functioning terribly well and when I went on that climb with him I did not want him to be in the lead."

"Then Tom went climbing in the Alps with a friend, Dick Viney. We don't know what happened, but it looked as if Tom was in the lead and he fell from above, which put tremendous strain on Dick. I lost two very good friends."

Tom Bourdillon died on 29 July 1956, aged 31.He had been married for four years and his son, Simon, was 10 weeks old. His widow is still alive. With hindsight, he should not have attempted that last climb on the east buttress of the Jagihorn, but as Simon Bourdillon said: "Mountaineering was his principal love. How do you ask someone whose principal love is to climb to stop?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments