It happened one Christmas

'Tis the season to tell a cracking good yarn. We asked five of our favourite columnists to reveal their Yuletide memories from first loves, via crazy horses, to doorstepping Felicity Kendal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

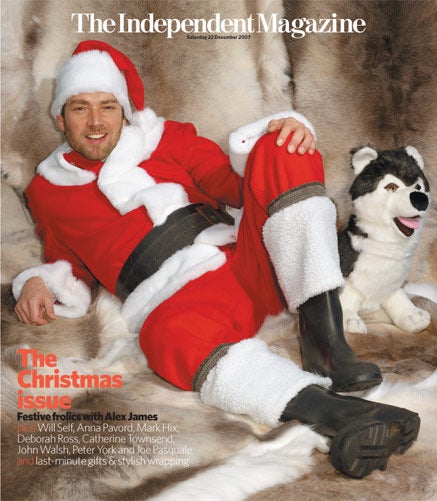

Your support makes all the difference.Alex James - Clodie and the choir

Christmas is my favourite time of year. I enjoy it more and more as I get older but I particularly remember my final Christmas at primary school. After that we wouldn't be children any more, if we still were then. The headmaster, who taught science, when he felt like it, had asked us all to bring in samples of alcoholic drinks to test their pH values: clearly irresponsible, if not completely mad. My mum gave me half a dozen carefully accumulated miniature bottles of various spirits and my friend Phillip Simmonds' mum, who ran a hotel, had been even more generous. Phillip and I decided not to declare our resources, but pool them and open a bar in the library at the back of the classroom.

We sat next to each other at the grammar school the following year that was an all boys' school but for the time being we were surrounded and preoccupied by girls and booze ... and we'd both fallen in love ... and it was Christmas.

Our teacher, Mr Mann, was quite scary, especially if you forgot your recorder, but he was a genius. Genius is the scariest thing there is. It makes one look so silly. I'd dropped out of recorder lessons by then, although I did enjoy plonking around on the class piano at lunchtimes after a few slugs of "cherry herring", the house special. As part of the Christmas jollities one afternoon, Mr Mann had shown us all how to take the piano to pieces and put it back together, something I had to do a few times myself as I dragged the piano my dad bought a couple of years later up and down the narrow staircases of my first London homes.

Mr Mann said that the first eight people to learn all the words to the carols for the combined schools Christmas concert at the Bournemouth Winter Gardens would represent the school and perform on the stage. I wanted to be one of them I was a show-off, still am. That was one reason, but it wouldn't have been enough on its own. My mum went to the concert every year, that was another. But if I didn't admit it to myself at the time, the main reason I wanted to be in the choir was that I knew Clodie would be. She was the best in the class at music. She even had a guitar, and in my 11-year-old way I was madly in love with her, but I couldn't tell her.

Learning the words to the carols wasn't a problem. I knew most of the first verses, everybody does. The latter verses of some of the classics didn't make that much sense to an 11-year-old, though. "Ding Dong Merrily on High", a preposterously brilliant song title when you think about it, gets even sillier towards the end. I can still remember the last verse. It starts:

Pray you, dutifully prime

Your matin chime ye ringers

Even now I can't recall it without smiling.

I learnt all the words to all the songs and gave Mr Mann and the rest of the class an audition, a tuneless interpretation, as he jangled the reassembled piano. I did know the words, though, so I was in, by rights. I was the only boy to qualify and I was also the only one who couldn't sing. I wasn't in the regular choir and not having been able to keep pace with the recorder honkers, had dropped out of music completely. I wonder if it hadn't been for that concert whether I would ever have been brave enough to jump back in.

It is absolutely terrifying to take the first few steps in singing. Singing is a bit like swimming, a kind of floating. In fact, it's much scarier than swimming, because you have to dive straight in to find out how to float. There is no shallow end. You're either singing or you're not. The audition was a plunge into a pool of terrifying scrutiny. Singing is no more difficult than swimming, though, and the best way to improve is to perform with people who are better than you. Under Mr Mann's strict diligence and the exquisite buoyancy of the girls' voices, in the weeks before Christmas, immersed in its music, I quickly became a singer. By the time the concert arrived I was singing harmonies. Harmonies aren't beyond anybody who is shown how to do it properly, and there is nothing more spiritual and warm than voices rising in consonant agreement.

We were at the top of the school and it was Christmas and the concert choir had a glamour that none of my other bands have recaptured. I suppose it was because it was the first time I'd performed properly and more importantly, it was bringing me closer to my first crush. In the week of the shows at the Winter Gardens the well-drilled concert choir made a brief tour of appearances at old people's homes and day centres around Pokesdown and we were a hit. We were good, man.

The combined concert choirs of all the schools in the area finally took to the stage at the Winter Gardens. The mums all came and cried. My mum went twice. Mr Mann said that people who lived near each other should share lifts and on the last night I gave Clodie a lift. It was some script. That night was my dad's turn to go; actually he'd been already with my mum. This time he was bringing my granddad. On the way home we got chips. Chips, my dad, my granddad and the girl, at Christmas. Nothing has ever been so perfect. I still couldn't tell her I loved her, that's way scarier even than singing, but she knew. My dad knew, I'm sure.

I don't hold the headmaster responsible for anything that happened later, but I do thank Clodie, who I never spoke to again after kissing her on the last day of junior school, for leading me towards music and love, one enchanted Christmas three decades ago.

May you beautifully rhyme

Your evetime song, ye singers.

Catherine Townsend

Snowed in

I'd always been nostalgic for the white Christmases of my childhood, but the year that I spent snowed into a bar with my cousin, an unlimited supply of alcohol and an incontinent greyhound was a harsh reminder that sometimes, a perfect setting isn't all it's cracked up to be.

I was 20 at the time I went to visit my cousin, Lauren, who is three years older than me and practically my sister. She was managing a bar in a small Colorado ski town, and living in the flat upstairs, so the plan was for me was to spend a few days with her and fly out right before Christmas and celebrate it back home with my mum.

Lauren loved the holidays, so the bar was decked out with over-the-top chintzy decorations, including an edible miniature manger scene made of pretzel sticks, sugar cookies and gingerbread that she'd spent a week preparing. Even her greyhound, Oscar, was wearing a sweater and little reindeer antlers.

As usual, we had a fantastic time, despite the fact that I'd never skied before in my life. I found the mountain air meditative, not to mention the adrenaline rush of tumbling down the hill in the company of Roger, a very cute ski instructor.

The night before my departure, Lauren and I threw a Christmas dinner bash where we spiked the eggnog with a lethal amount of bourbon, and I ended up in the hot tub with Roger, and then went back with him to his place.

Unfortunately, I woke up the next morning with a raging hangover and realised that a huge blizzard had hit during the night, dumping 12 inches of powder outside.

Roger very chivalrously snow-shoed me back to the bar, where Lauren broke the news that roads to the airport were shut. I had two options: I could leave the next day and risk spending Christmas day stuck at the airport trying to get on to a flight, or stay and party.

Not surprisingly, I chose the latter option. Lauren and I began planning the mother of all Christmas fêtes.

Ironically, the random cast of characters who showed up were probably the closest to Santa Claus I've ever got portly locals with copious amounts of facial hair who propped up the bar on a regular basis, mixed with the international staff who, like me, were stranded.

At first, a lot of us were in tears about not being able to get out of town. But then, a funny thing happened: trapped in the wilderness, suddenly we didn't feel like a bunch of losers who were spending the holidays alone we had a common cause.

We danced, drank and fired up the karaoke machine, singing everything from Journey to "Jingle Bells". We couldn't get to the main grocery store on the outskirts of town for Lauren to get her turkey, but the pizza joint around the corner was still working, so our Christmas lunch consisted of ham and pineapple pizza.

I can't think of another Christmas dinner where the topic of conversation was how soon we would all have to resort to cannibalism, but weirdly having to live without some home comforts for a few days reminded us how lucky we were. Everyone kept their spirits high, even on the second night when we briefly lost power and had to light candles and feel our way down to the basement.

Oscar took the opportunity, while we were distracted, to wolf down Lauren's entire manger. I got to him just as he was chewing on the baby Jesus marshmallow. He got violently ill, and I'd soon used every towel in the place to clean up after him. Lauren lost it momentarily, but I stayed positive. To cheer her up, I put on my red mini-dress and mistletoe hat and passed out shots of peppermint schnapps.

Obviously shopping was out, but Roger very sweetly came back with a gift he'd obviously wrapped at his flat. "It's a torch," he explained when I opened it. "Sorry it's second-hand, but right now that's the best I can do."

"No worries," I said. "It's definitely the gift that keeps on giving!"

Since the night of the storm, I've learnt to expect the unexpected, and to not beat myself up if things aren't perfect. I've spent many Christmases on my own since then, and even when times are tough I try to focus on what I have, instead of what I'm missing.

Anyone can fake a smile at a picture-perfect gathering opening presents by a fire, but singing Christmas carols with complete strangers in the face of dwindling loo paper? That's a real Christmas miracle.

Virginia Ironside

Bitter almonds

Christmases in the Fifties were, in my memory at least, rather bleak affairs. Certainly in our household, there was very little letting-down of hair. We never celebrated New Year, and birthdays, if they were remembered at all (my parents celebrated my own birthday on 4 February for about 11 years until they remembered I had been born on 3 February), were usually over by about nine in the morning, after a few presents had been opened.

We rarely put up decorations at Christmas, except perhaps one paper chain made painstakingly by me at school, and our tree was usually a small and sparse affair decorated with mangy tinsel and a few glass balls. Christmas lunch was always a chicken, the smell of which mingled with the curious odour from the paraffin heaters distributed round the house to take the edge off the cold.

I'm not playing the "poor me" card I think everyone had Christmases rather like ours in those immediate post-war days but I do remember one particularly grisly 25 December, when I was eight years old.

In the morning I had got the usual excellent stocking, which my parents packed tight with all kinds of bits of nonsense metal puzzles, magic drawing books, an ocarina, a glass animal. A cracker was pinned to the top. I woke early and took it to open on my parents' bed. My father and I struggled over the puzzles, and then my mother got up to put on the kettle. After breakfast, all the big presents were laid out on the sofa. I had the most, of course, but I was almost as excited to open mine as to watch my parents opening theirs.

In the autumn of 1952 I had begged my mother to teach me how to knit. She bought me some huge needles and I chose thick, lime-green wool to make my father, Christopher, a scarf for Christmas. I knitted in bed when he thought I was asleep. In the end the scarf was a vivid green snake, about seven feet long.

As for my mother, Janey, knowing she adored marzipan, I had saved up my pocket money to buy her some marzipan animals I had seen in a sweet shop. My mother was cold and difficult to please, but I longed to give her something that she could enjoy. I wanted to see the delight in her face as she popped my present in her mouth and swooned with delight at the flavour... and I spent ages choosing a marzipan heart, a marzipan rabbit and a marzipan chicken.

When my parents took my presents from the sofa, my father slowly opened his, with appropriate rolling of eyes and: "What can this be? I'm completely baffled! It isn't a jersey... a flying saucer... oh look! It's a scarf! It's exactly what I wanted!" He put it round his neck at once, delightedly admiring himself in the mirror.

My mother had already opened her present while all this was going on and stared at the marzipan animals in confusion.

"Well, go on, eat one!" I said.

"I'll eat one after lunch. Otherwise I might spoil my appetite," she said, rather coolly. "Thank you so much, darling."

This particular Christmas we were having Christmas lunch with my spinster great-aunts on my father's side, the Misses Ironside. Rene was tall, thin and forbidding, the long lobes of her ears nearly reaching the shoulders of a formal suit, made of Scotch tartan, usually worn over a high-collared lace shirt pinned with some kind of Celtic brooch. Nellie, her sister, was the complete opposite small, round and warm. Both of them had snow-white hair, pinned into buns at the tops of their heads.

The problem was that Rene was the headmistress of the school I attended from two years old to 16 and the aunts lived in the school itself, a huge, stuccoed, pillared house in Elvaston Place in South Kensington.

That Christmas day we walked from our house, my father still kindly wearing his scarf, my mother carrying the present for the elderly sisters, a bottle of wine. It was really, of course, for her, rather than them, as she needed fortification to get through the gruelling two hours that lay ahead. It was wrapped in the ironed paper kept from one of last year's Christmas presents.

This year my great aunts' black sheep brother, my grandfather and his new wife, Dolly, were there as well. My grandfather, having been struck off as a doctor for dreadful malpractices including seducing some of his wealthy female patients and introducing them to drugs, had eventually got a job as a private anaesthetist but was now retired. He was no longer dashing and good-looking as he had been when young, but fat and bald, though he still had an uncomfortably flirtatious way with him. He kept offering me cigarettes and calling me a "little sauce-box" a description that could hardly be less appropriate; at eight years old I was always dumb with shyness. We stood about in the school sitting room a space the pupils never entered except to be reprimanded by Rene. It being a progressive school there were no punishments. It was bad enough for Rene to ask what was one's misdemeanour and then comment, in strong, disapproving Scottish tones: "Well, I hope you never have to be sent to me again!"

Today, Nellie offered us all a very small glass of sherry. In a little glass dish lay a few tiny salted biscuits.

"Where did you get that perfectly lurid scarf, Christopher?" asked Dolly, her bright red lips pursed in disapproval.

Dolly, a millionairess, had been one of my grandfather's patients. She had a high forehead, wriggly hair, hard lipstick and wizened face. The moment this wealthy creature woke up from an operation she saw the stunning good looks of her anaesthetist, my grandfather, staring down at her and decided to marry him. He spent the rest of his life in their mock-Tudor house in Esher, kept on an extremely tight rein with a very small allowance and never allowed up to London except in the company of her chauffeur, who dogged his every move.

"Lurid?" said my father. "It's splendid. Virginia knitted it for me all by herself!"

"And you, Janey? What did she give you?"

My mother struggled to remember. "Um, some marzipan, I think," she said. "Wasn't it, darling?" she added. I felt my heart sinking.

At precisely one o'clock we made our way to the school dining room in the basement.

The cold light of the silent South Kensington day filtered in through the barred window on to the same oak trestle table I sat at every school day of my life, engrained with fat and the smell of old cabbage. There was nothing to drink except tap water in an earthenware school pitcher.

"Oh, what about the wine?" said my mother, pretending she'd just remembered it and hadn't been craving a glass and only then was it grudgingly produced. "Some for you, you young rascal?" said my grandfather, as he pretended to pour some into my glass.

Conversation, I seem to remember was about, variously, the weather, how erratic was the service of the No 49 bus and whether there were any ospreys nesting in Scotland this year.

Later, over coffee, my grandfather stuffed a 10 bob note into my hand telling me "not to spend it all on ice-cream, you cheeky monkey!" while Rene presented me with a book on Norman architecture.

As soon as we could politely leave, we rushed home. Even my father agreed that it had been "Ghastly!" As we walked, I fingered his scarf, examining the loopy stitches.

"Do you really like my present? Is it warm?" I asked him, fishing for a compliment.

"It's just wonderful, particularly in that freezing dining-room," he replied, having worn it nobly throughout lunch.

"And when we get home, you can eat one of your marzipan animals, mummy!" I said. "Which one will you choose first? The rabbit? Or the chicken? Or the heart?"

My mother laughed. "Oh, I don't intend to eat them," she said. "I am going to keep them so I can look at them for ever!"

And I felt, suddenly, terribly disappointed.

Deborah Ross

Chasing Felicity

It was 1988 or thereabouts and it was my first job on a national newspaper, a tabloid, and I was keen as mustard, or would have been had I not been so frightened and hadn't hidden in the Ladies for vast stretches of time. I'd started at the paper as a news reporter but once it became apparent as it so quickly did that I would not recognise a news story even if it were to happy-slap me and take a photograph, I was shunted to "showbiz" as a "showbiz reporter". This was seen as the softer option, even though it did not seem like it to me, and my time in the Ladies did not lessen appreciably

Anyway, that year I was co-opted to do the Christmas Day showbiz shift. I think this was because I was new-ish and Jewish. New-ish would have done, Jewish would have done, but the fact I was both seemed to seal it. (Hey, you, new Jew, you're doing Christmas Day.) I didn't mind too much. I'd been told it would be a doddle. Most of the paper would have been put to bed on Christmas Eve. I could amble in late, flick though a few magazines, make a few personal telephone calls today's generation don't appreciate how hard it was to waste time before the internet and then go home early, all for extra pay and a couple of days off in lieu. Days off in lieu, I still maintain, are far better than days on in loo.

So I ambled in on Christmas Day, late, and started flicking though the magazines and was just building up nicely to the personal phone calls when the news editor summoned me. (God damn it. I'd been lulled into a false sense of security. Why hadn't I had the sense to hide in the Ladies this time?) He did not, by the way, summon me with a "Hey you, new Jew" which was nice, at least. He said he wanted me to drive over, right now, to the actress Felicity Kendal's house. Earlier in the week, it had been reported that she had left her husband, the director Michael Rudman, for the playwright Tom Stoppard, but had yet to say anything about it.

It was made very clear to me that the whole world was waiting for a quote from Felicity, including the Pope and Nelson Mandela but probably not Cheryl Baker who, post Buck's Fizz, was concentrating very hard on her television career. I did not say: "What? It's Christmas Day and you want me to knock on Felicity Kendal's door to ask her if she's shagging Tom Stoppard?" I did not say that because even I knew I should at least appear keen as mustard. I probably said: "I'm on to it!" And then: "They don't call me Scoop for nothing!"

After a detour via the Ladies (a quick cry, if I recall rightly), it was into my car my first car, a Mini Metro, which had the unique feature of sometimes rolling backwards while driving uphill and made for the address I'd been given.

It was in Chelsea, in one of those exquisite Georgian squares where the creamy, tall houses cost an arm and a leg, then your other arm and your other leg. These were limb-hungry properties. I parked up near her house, and said to myself: OK, I'll give it 10 minutes, then I'll knock. It's best not to rush things.

Ten minutes went past, as did another and then another. OK, I said to myself, another 10 minutes and I really, really, really will do it. I know, I know, why so reluctant to doorstep Felicity Kendal on Christmas Day, probably as her children are gathered around her, to enquire about her sex life? After all, the Pope needs to know, as does Nelson (but not Cheryl). Actually, I am not noble (ask anyone) and not even particularly moral (ditto) but this felt bad and I did not like it. On the other hand, it was probably just cowardice. I am a hopeless coward and once even dialled 999 because there was a bee in my bedroom.

Finally, I did walk up the steps to her front door. Aside from anything else, the heater in the car did not and had never worked and, boy, was I cold. It was a nice door; green, decorated with a holly wreath. Light was blazing from the bay window so I thought that, even though I would knock, any minute now, I'd just take a peep. It was a beautiful living room, with a vast old fireplace, a roaring fire, photographs of her children all along the mantelpiece, empty drinks glasses, evidence of presents having been unwrapped and the most magnificently decorated Christmas tree wouldn't you just know, anyway, that Felicity Kendal would have the most magnificent Christmas tree? There was no sign of anybody it was time for Christmas lunch and they were probably all eating in another room but it was still all so warm and cosy-looking and lovely. Happy, even. And I couldn't do it. Just couldn't.

I returned to my icy car, had another short cry, then drove downhill, when I was supposed to be going up it to the nearest phone box to call the news desk.

"No one in," I reported because, as you know, this is what reporters must do: report. "And it's all dark. I think she is probably away," I added.

I got away with it superbly, right until the following morning, when a rival newspaper came out with not only a quote from a Felicity ("...as she said yesterday from her Chelsea home") but a photo of her on those very steps. It was then that I knew there was nothing for it: I was just going to have to sleep my way to the top.*

*Deborah Ross also failed to sleep her way to the top which is why she has languished at the bottom until this very day.

John Walsh

Way out west

When my parents retired in 1983, and went back to live in the Ireland of their youth, Christmas went with them. They packed up the ancient crib. They took the fat spools of crinkled crêpe decoration that festooned the living-room walls every year, the three strands of fairy lights and the brown soup tureens that were only ever used on Christmas Day. They left the family homestead on London's South Circular Road, and legged it back to the mystic west.

The first Christmas I spent with them in Ireland, though, was at my sister's house. She'd got there before them. Driven by some nostalgie de la boue, Madelyn had moved to Ireland years earlier, married the vet from Athenry, our father's village, and set up home there. Much rejoicing had followed: she was like a prodigal daughter, but one generation removed. And now my father, a genuine exile, was back after 33 years, and that too deserved celebration. Ireland in those days still exported its best children and welcomed them back warily if they were visiting to show off the wealth they'd accrued in Toronto or Boston; ecstatically, if they were home for good.

So Madelyn's home in Athenry was crammed with well-wishers. Neighbours dropped by to see my sister's new baby, Annabel, and discovered my father their old schoolfriend from half a century back drinking tea in the kitchen. Word got around, and more people came to see the wondrous sight, some of them bearing gifts. A keg of bitter was rolled round from Hanberry's Hotel on Christmas Eve and singing broke out around the piano. My mother, sternly Catholic, mellowed enough to accept a Harvey's Bristol Cream, and clucked to the parish priest about declining vocations.

It was all so rich, so authentic. The Christmas tree in the drawing-room didn't come from a garden centre; Frank, my brother-in-law, hacked it down himself in Derrydonnell Woods. The merrymaking wasn't done in the apologetic English way; it was heartfelt, euphoric, Dickensian. There was even a genuine Christmas baby. I stole upstairs to look at her. Annabel lay on her back, eyes tight shut, tiny arms extended, as if she was flying. She was the most beautiful thing I'd ever seen.

So there was my sister Madelyn, starting a new life of motherhood. There were my parents, newly grandparented, starting a new life surrounded by old friends, back in the Irish heartland they'd departed in the late 1940s. And here was I, unmarried, childless, a freelance hack with a chilly flat in south London. I didn't belong in this flushed and vivid company. I felt thin, sketchy, under-realised, a badly drawn boy.

Christmas Day passed in a blur of Catholic rituals and pagan appetites. After the plates of turkey, stuffing, bacon, sprouts, roast spuds, boiled swede and cranberry sauce had been washed down with Blue Nun and Guinness, the neighbours began dropping round all over again. It was unbearable. So when Frank wondered aloud if he should take the horse out for some exercise, I jumped at the chance.

"Let me take Scobie out," I pleaded. "I could do with some fresh air." "You think you'd be able for him?" asked Frank, doubtful that a London Sassenach could ride a great, black, muscle-bound, 16-hands gelding. "It's only a stroll up the road," I said. But I admit I was apprehensive as I led the animal out the gate. I'd ridden horses before, on Irish summer holidays. I could trot without much agony in the coccyx; I'd even cantered, in the Brecon Beacons. But Frank's horse seemed so huge, its great head so noble, its bearing so patrician, I suddenly felt doubts. Its shoulders and flanks seemed to quiver and flow alongside me like a slow-motion tsunami of horseflesh, massive, heroic, alarming...

For God's sake. It was only a horse. Jeans tucked into Frank's hunting boots, leather hat clamped on head, I climbed on to the stone alcove beside the gate and swung a leg over. We set off. The sun was declining fast as the horse walked down the high street, and over a tiny bridge between two dry-stone walls. I sat upright, feeling elated on my enormous charger, glad to be out on my own.

We ambled on. The low sun eased itself slowly on to the line of the horizon. Then, two fields away, a cow let out a painful, lowing sound. Scobie changed. A tremor ran through his spine and shook his flanks. Then he bolted.

My hat flew off and disappeared. At a turning, a Mini switched its headlights from dipped to full-beam and Scobie reared, his front legs three feet off the ground. I clung on, as I'd been clinging for the past minute, only more so. My rear end ached from crashing on to the saddle. I pulled hard at the reins, and Scobie finally halted, quivering.

It was dark as Hades. It was cold as Alaska. There were no signposts. All the dry-stone walls looked identical. I hadn't a clue where we were. Up ahead was a field with a lit-up house in it and I rode over gratefully. But then I realised: I couldn't trust myself to dismount because a) I might never get back on again, and b) the horse would leave without me. So I sat and shouted, pathetically, at the front door: "Hello? Is anyone there? Can you direct me to Athenry?"

It was pure Longfellow. Nobody came. Nobody answered. I thought I saw a curtain twitch as someone peered out, wondering who in God's name could be sitting there in the darkness, becalmed between earth and sky, trying to find a way home on Christmas Day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments