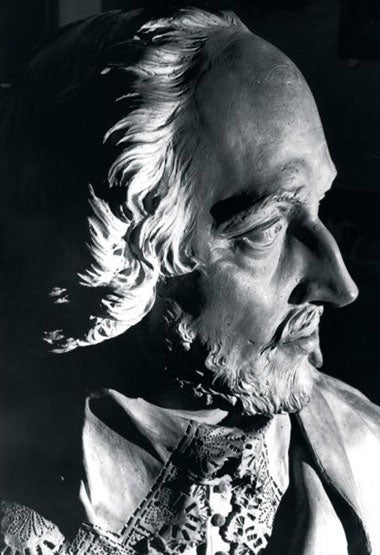

Is this bust the true face of Shakespeare?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A bust that has stood scarcely noticed in a London gentleman's club for 150 years is being hailed as the first authentic contemporary sculpture of William Shakespeare.

Forensic imaging techniques and medical studies comparing the so-called Davenant bust in the Garrick Club with a 17th-century death mask of the writer has convinced a German professor, Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel, that the bust was made in the early 17th century, when the playwright was still alive, and not the 18th.

The claim comes on the eve of a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, called Searching for Shakespeare, which is to present four years of research on all previously recognised images of the Bard. The new research, which is published in a book, The True Face of William Shakespeare, next month, also questions the provenance of one of the other known portraits of the playwright and poet - known as the Flower portrait.

Professor Hammerschmidt-Hummel's research into the Davenant bust involved forensic experts from the German equivalent of CID, doctors, ophthalmologists and archivists.

It was long believed to be by the 18th- century French sculptor Roubiliac. But the professor traces the bust back to the times of Shakespeare through the diary of William Clift, curator of the Royal College of Surgeons' Hunterian Museum in London. He discovered it in 1834 outside No 39 Lincoln's Inn Fields, which was adjacent to the Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre.

This was previously the Duke's Theatre and owned by Sir William Davenant, Shakespeare's godson and, perhaps, natural son, who owned many Shakespeare mementoes, including the famous Chandos portrait which most experts agree is genuine and contemporary.

"He must have been alive," the professor said. Superimposing the bust with a 17th-century death mask from Germany and other likenesses showed perfect matches between the forehead, eyes and nose. The lips on the death mask were thinner than those on the bust, but they would have shrunk with the loss of blood pressure after death. But the professor courts even greater controversy by claiming the so-called Flower portrait, which has been investigated by the Portrait Gallery and dismissed as a fake, is not the Flower portrait she originally examined 10 years ago.

Speaking from Germany yesterday, she said the portrait she examined had shown evidence of swelling around the eye and forehead, which she believes shows Shakespeare suffered from a kind of cancer of the tear duct known as Mikulicz's syndrome. But the one about to go on display at the gallery does not have these indications of illness - suggesting it is a copy of the one she tested in 1996.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments