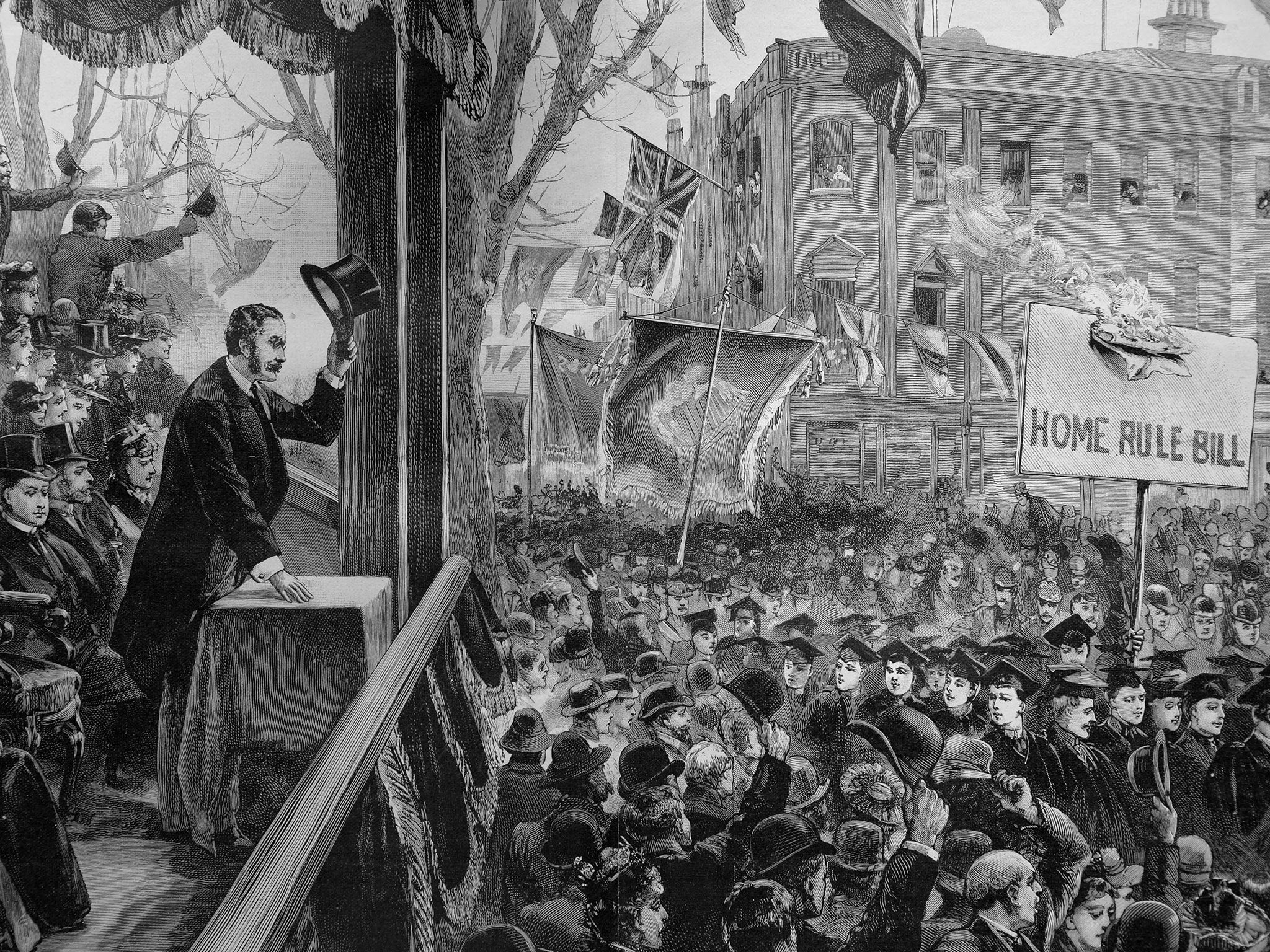

Devo max explained: The biggest constitutional change since Ireland got home rule

David Cameron’s granting of devo max guarantees a dramatic – and unpredictable – change to the way we are all governed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is David Cameron promising?

In his statement outside Downing Street yesterday morning, David Cameron declared that the Scottish referendum result had “kept our country of four nations together” but it was time for a new constitutional settlement – not just for Scotland but for the rest of the United Kingdom as well.

He said that the Scottish Parliament would have new powers over taxation, spending and some aspects of welfare policy with the specifics to be drawn up by an independent commission. He said he hoped to get cross-party consensus for the plan – with draft legislation to be drawn up by January and a Bill to go to Parliament after the next election.

At the same time, Mr Cameron announced that it was time to address the question of English votes for English laws – otherwise known as the West Lothian question.

What is the West Lothian question?

It is a conundrum that has existed in UK politics ever since Westminster began devolving powers to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. At its heart is this question: Why should Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish MPs be able to make laws that will not affect the people they represent? For example, why should they decide how NHS money is spent when it won’t have any impact on their own constituents?

Taking Scotland first: what specific new tax powers are they going to get?

This is still unclear. What we know for sure is that under the Scotland Act 2012, there will be a new Scottish rate of income tax (SRIT) from April 2016. This will reduce the basic, higher and additional rates of income tax by 10p in the pound for Scottish taxpayers, with the Scottish Parliament then able to take a decision about what rate of SRIT to add on top to the three rates set in Westminster. Scotland would keep all the money raised from the SRIT, instead of it going to the UK Treasury.

For example, if the SRIT was set at 10 per cent, Scottish workers would pay exactly the same levels of income tax as currently, but 10p in the pound would be retained by Holyrood.

An SRIT of 9 per cent would mean the rates paid by Scottish taxes were lower and a Scottish rate of 11 per cent would mean they were higher. In addition, stamp duty, land tax and landfill tax will also be devolved.

As part of the new settlement Labour wants to increase the tranche of income tax retained by the Scottish Parliament from 10p to 15p.

The Tories also want to give Scotland more control of income tax bands as well as devolving air passenger duty. Exactly what these new revenue-raising powers will be is set to be examined by Lord Smith of Kelvin who is expected to make his final recommendations in November. But one thing is clear: as Scotland would get to keep these revenues to spend as it likes, there would be a reduction in the amount currently given to Scotland by the UK Treasury under the so-called Barnett formula.

What is the Barnett formula and why is it controversial?

The formula was introduced in 1978 and distributes expenditure to the four UK countries to fund sectors such as health and education for which the devolved administrations have responsibility. It is calculated in rough proportion to current population.

Its basic principle is that any increase or reduction in expenditure in England will automatically lead to a proportionate increase or reduction in resources for the devolved governments. However, it has long been criticised for being unfair due to historical anomalies over the way population was originally calculated. Last year under the formula, Scotland got £10,152 per head; Wales, despite being much poorer, got £9,709, and England got £8,529.

As part of the last-minute plea to Scottish voters, the main party leaders agreed to keep the formula. But what is still far from clear (and open to negotiation) is how it will be reduced in line with the new revenue-raising powers that Scotland will have.

What other powers will Scotland get?

Again, this has not been decided. The Tories have talked about devolving some aspects of welfare spending to Scotland – such as the payment of housing benefit. This was done mainly to allay anger over the bedroom tax. But if they do this it would drive a coach and horses through plans for UK-wide universal credit which is to include housing benefit.

How will all this affect England?

David Cameron was very clear yesterday that devolving further powers to Scotland will mean that the question of English votes for English laws also has to be addressed, in what will be the biggest constitutional change since home rule for Ireland in 1920. He was deliberately vague about the specifics but said that William Hague would chair a cabinet committee to draw up proposals for how such a system might work. He said he wanted this to be done on a cross-party basis on the same timescale as Scottish devolution.

How could this work in practice?

In 2012, the Government set up the McKay Commission to consider how the House of Commons might deal with legislation that affects only one part of the UK. It set out a series of complex options – including a special committee of English MPs to rubber-stamp English bits of legislation. This report, which was ignored when it was published, is now likely to be dusted down.

But any move of this kind would have very practical political implications. For example, at the next election, if Labour won power with majority of less than 41 (its current number of Scottish MPs), it would not command a majority of English MPs to implement its manifesto pledges on everything from the NHS, to income tax to schools and possibly welfare payments. So in effect, you could have a national Labour government whose English policy is controlled by the Conservatives in coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

Does that mean we could never have another Scottish prime minister?

No – but it would mean that the prime minister would not be able to vote on a large number of his own government’s policies.

What does Labour think about this?

It doesn’t like it at all but it finding it hard to argue against the logic of English votes for English laws. Yesterday, the party proposed that instead of Mr Cameron’s plan, there should be a constitutional convention set up after the election to “determine the UK-wide implications of devolution and to bring these recommendations together”. This looks like an attempt to push the issue into the long grass and avoid having to take a position ahead of the next election where the issue will certainly form a key part of the campaign.

What happens now?

Intensive negotiations, both over the specifics of new powers for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and a new settlement for England. But with a general election looming it is difficult to see where consensus can be found. Mr Cameron said he want the two issues to be resolved concurrently on the timescale that the party leaders pledged to Scottish voters. That might be impossible.

Ultimately this extraordinary constitutional change will have to be approved by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords in an Act of Parliament after the next election.

Given that the far smaller constitutional question of House of Lords reform is still unresolved after 100 years, it will be a rocky road ahead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments