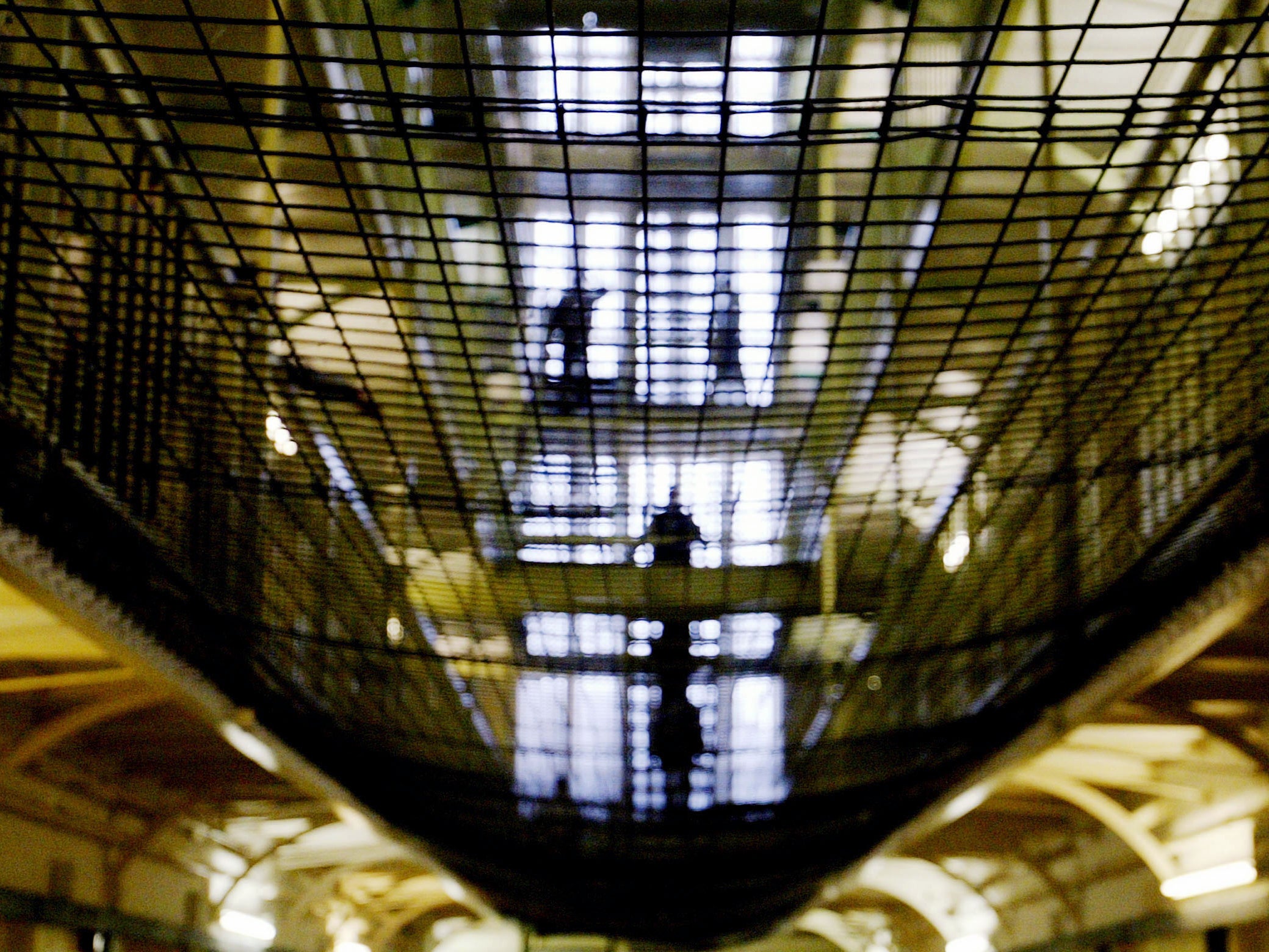

Mentally unwell women are being sent to prison instead of hospital due to lack of NHS beds, MPs warn

Shortage of NHS beds means women with acute mental health problems sent to jail ‘for their own safety’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mentally unwell women are being imprisoned unnecessarily as self-harm rates surge in prisons across England, MPs have warned.

Evidence from the Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons to an all-party parliamentary group (APPG) revealed 68 women, remanded to three jails in the 12 months to August 2021, should have been moved elsewhere due to their mental illnesses.

Women with acute mental health problems were being remanded to prison “for their own safety” due to a shortage of NHS beds and lack of appropriate services within the community, a report to the APPG said.

The APPG on women in the penal system has now called for the repeal of legislation that gives the courts the power to remand people in prison “for their own protection”.

Pre-pandemic self-harm rates for women in prison were five times higher than men, the report said. This increased to up to eight times after restrictions to curb Covid-19 were implemented, with some women self-harming daily.

In one prison, HMIP found 20 women sharing just two toilets.

Previous inspections found damp, mould and evidence of an ant infestation in Downview prison. Living accommodation units were described as ‘completely inappropriate’ in Eastwood Park prison.

Women were also kept in their cells for up to 23 hours a day during the pandemic, which meant that undertaking activities to improve their mental health, such as running, were difficult.

Jackie Doyle-Price MP, co-chair of the APPG, said: “From filthy living conditions to alarming evidence about self-harm, our inquiry has considered in great detail the impact that imprisonment has on women’s health and well-being.

“This requires urgent attention. The government has published a Prisons Strategy White Paper, which recognises that women in the criminal justice system have complex needs. Unfortunately, however, the current proposals represent a missed opportunity to address the specific issues women face.

“The focus should be on stopping unnecessary use of custody – not prison expansion, which would only pull more women into a system that fails to provide the care and support they require.”

The briefing states that most of the women in prison did not need to be there. There were 4,787 first receptions of women into prison in the year ending June 2021, with more than half of the women on remand. One in three were in for a sentence of less than 12 months.

The inquiry heard about the psychological struggles women in prison faced in the pandemic, exacerbated by restrictions limiting contact between visitors.

HMIP reported that one woman found family visits so upsetting that she made the decision to stop. She found it unbearable to see how distressed her children were at not being allowed to hug her.

Some prisoners missed hospital appointments due to a lack of staff, and two babies died in women’s prisons over the last three years.

NHS Inclusion told the APPG that women serving shorter sentences and those travelling to and from prison frequently could face disruption to any treatment or medication they might have been receiving before custody.

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “We are clear that custody should be the last resort for women, and the number entering prison has fallen by nearly a third since we launched our Female Offender Strategy in 2018.

“We have also made significant improvements to support female offenders – building new prison places to increase the availability of single cells and in-cell showers while providing greater access to education, healthcare and employment.

“In addition, we are investing heavily in rehabilitation and treatment programmes, which will see £80m help fund drug treatment services so more women can turn their backs on crime.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments