Brexit: What is it and why are we having an EU referendum?

The big EU questions: The EU debate so far has been characterised by bias, distortion and exaggeration. So until the end of the referendum, we are running a series of question-and-answer features that will try to explain the most important issues in a detailed, dispassionate way

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we having a referendum?

That is probably a question David Cameron is asking himself – and the answer is not straightforward.

The British public have not had a direct say on our relationship with Europe since 1975, when we voted to stay in what was then the European Economic Community. In the intervening years, Europe has changed.

Then, we were voting on joining a “Common Market” of nine member states, with a population of 250 million. Today, the EU has 28 member states (19 of which share a single currency) and a population of more than 500 million. Importantly, successive treaties since 1975 have seen the European Union transform from a trading arrangement to a fully-fledged political union, giving Brussels influence over many other areas of policy.

Ever since the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which created the modern EU, there have been those calling for another vote to take into account how things have has changed, with Eurosceptics claiming that membership now represents an unacceptable transfer of powers from our Parliament to Brussels. It has been a running sore for the Conservative Party in particular, with many MPs and much of the membership never fully reconciled to our membership.

But a long period of economic growth (until the financial crash of 2008) under two pro-EU Labour Prime Ministers, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, gave credence to the idea that being in the EU and its Single Market was good for Britain’s prosperity, and the issue was placed on the backburner for nearly 20 years.

So why has it resurfaced now?

When Mr Cameron entered Downing Street in 2010 he was determined to be a Conservative Prime Minister whose tenure was not marred by internal party warfare over Europe – or as he put it he didn’t want the Tories to “bang on about Europe”. He hoped that the presence – and necessity – of Lib Dem support for the Coalition would reduce the power of the anti-Europeans on his own backbenches and allow him to concentrate on his domestic reform agenda.

What went wrong?

In a word: Events.

Mr Cameron and the political class in general underestimated the groundswell of public resentment caused by the influx of European migrants to the country since accession of Eastern European countries in the early 2000s.

To begin with Polish plumbers, builders, waitresses and bar staff were generally welcomed. But the financial crash of 2008 and the fall in living standards it resulted in stoked resentments which politicians from all three major parties were too slow to recognise and respond to.

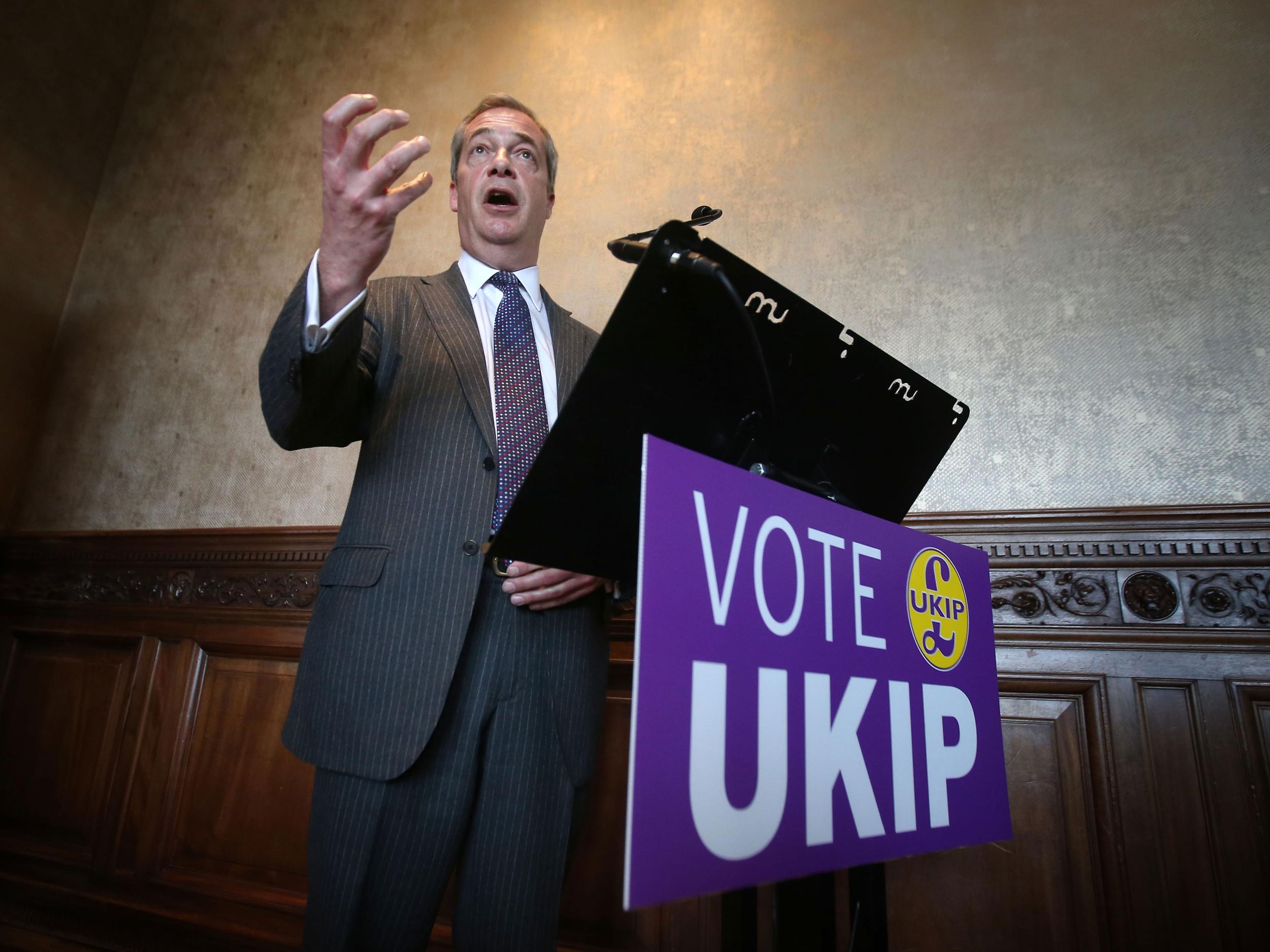

Into this vacuum stepped Nigel Farage and Ukip. In the 2010 general election the party polled around three per cent – just one per cent more than they had done five years before. But by 2012 Ukip fortunes had been transformed and some surveys suggested the party was being supported by up to 15 per cent of the electorate.

For Tory MPs facing re-election this looked ominous. They were worried, not that Ukip would take their seats but they would take enough of their votes to hand victory to Labour.

In private, and sometimes in public, they demanded that the Prime Minister give them something in their armoury to fight off the challenge – and that something was an EU referendum.

This would allow Tory candidates to go into 2015 able to assure their own anti-European supporters that only a vote for the Conservatives would give them a chance to have a definitive say over Britain’s future in Europe.

And so, in January 2013, Mr Cameron made his fateful pledge of an in/out referendum if the Conservatives won the 2015 election.

So was he in favour of a referendum himself?

We don’t know for sure but the answer is probably not. That being said, Cameron certainly felt he had little choice over the issue. His attempt to make the Europe question go away by promising a referendum if a UK Government ceded more powers to Brussels did not go far enough for Tory Eurosceptics. Meanwhile, there was a necessity to “shoot the Ukip fox”. Some of those around Mr Cameron – including the Chancellor George Osborne - are understood to have urged him not to go ahead with the pledge warning that it could have disastrous unintended consequences but he thought it was a gamble worth taking.

Why is that?

The main reason is that Mr Cameron thought it would never happen. He calculated that Labour under Ed Miliband would not back the plan and the Lib Dems were passionately opposed. Back in 2013 no senior Tory – including Mr Cameron – realistically thought they had a chance of winning an overall majority in 2015 and that another Coalition was likely. That being the case, most people believed that the referendum pledge would be the first thing to go in Coalition talks.

That was a bit of a miscalculation then?

Yes. But when they did win in 2015 Mr Cameron knew he had to embrace the referendum – and ensure that he won it. A vote was promised by the end of 2017, and Mr Cameron embarked upon his much-vaunted “EU renegotiation” – a long period of bargaining with the EU’s other leaders over the terms of Britain’s membership. Throughout, he maintained that his decision about which side to back in the referendum would only be made after the new terms were settled.

Eurosceptics in his own party weren’t convinced and were unsurprised when, in February, he emerged from marathon talks in Brussels with a new deal for Britain which he said was a strong basis for him – and his government – to back a Remain vote. Critics were not convinced that the changes amounted to much. Nevertheless, eager for the issue not to dominate the political agenda for any longer than necessary, Mr Cameron set an early referendum date – 23 June 2016.

And will the referendum be the final word on the matter?

Watch this space. Mr Cameron has ruled out a second referendum saying this is a “once in a generation, once in a lifetime” decision. Ukip leader Nigel Farage sees it differently, suggesting that a narrow Remain win would result in an irresistible clamour for another vote. Equally, there are those who wonder whether a victory for Leave would prompt a big new offer from Brussels that could keep us in the EU on very different terms – with restrictions on immigration, for example.

But for now, both camps are, officially at least, working on the assumption that the British people’s decision on 23 June will indeed be final.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments