Ulez: Everything you need to know as London’s low-emission zone expands

Sadiq Khan’s flagship policy will be enforced in a matter of days. Jon Stone looks looks at the details of the scheme - and how it divided the capital

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sadiq Khan is going ahead with the expansion of London’s Ulez (ultra low emission zone) on Tuesday, following the failure of a legal challenge against it last month.

But what is the policy, what is the thinking behind it, and why has it caused such an almighty political row?

What is Ulez?

Ulez already exists, and has done since 2019. Under the scheme, cars and vans that don't meet certain emissions standards (Euro 4 for petrol and Euro 6 for diesel) have to pay a £12.50 charge to drive into the Ulez zone. TfL says this means around 10 per cent of vehicles have to pay.

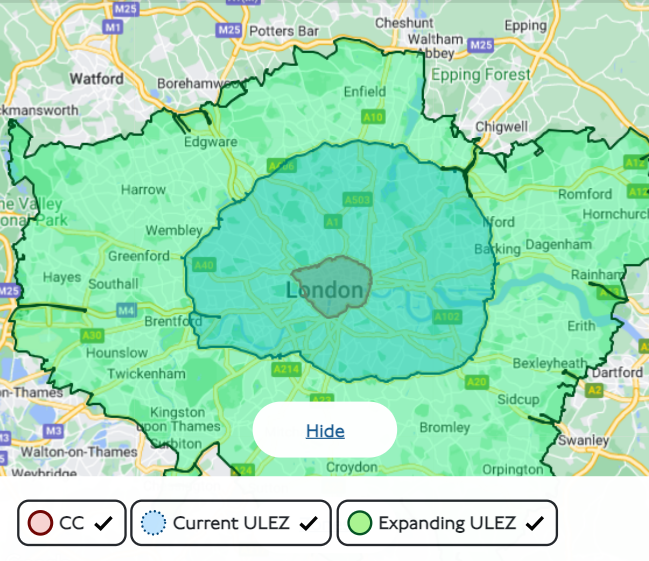

In 2019 when Ulez was launched, it only covered the same area as the central London congestion charge zone. In 2021, the scheme area was expanded to "inner London" – inside the north and south circular roads. This means it currently stretches to roughly Dulwich in the south and Finchley in the north.

The next step, which will take place on Tuesday, is to expand it to the whole of Greater London. This is what the current row is about.

What is for?

Around 4,000 Londoners die prematurely every year from the effects of toxic air, according to research by Imperial College London – with fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) the main culprits. Huge swathes of the capital regularly breach World Health Organisation legal limits on air pollution.

The aim of Ulez is to reduce this pollution. It does this in two ways: firstly, it discourages people in the most polluting cars from making as many trips in the capital, by putting a high price on them. Secondly, it encourages people with polluting cars to replace them with less polluting cars.

Revenue from the charge is also being reinvested into bus lanes and walking and cycling improvements, with the aim of providing alternatives for people to get around.

– How significant is the expansion?

Mayor of LondonSadiq Khan is extending the zone to cover all London boroughs from Tuesday.

– How many vehicles will be affected?

Transport for London (TfL) says nine out of 10 cars seen driving in outer London on an average day meet the Ulez standards, so will not be liable for the charge.

But Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency figures obtained by the RAC show 691,559 licensed cars in the whole of London are likely to be non-compliant.

This does not take into account other vehicles such as vans and lorries, or vehicles which enter London from neighbouring counties such as Essex, Hertfordshire, Surrey and Kent.

– How much is the fee?

The charge for vehicles that do not comply with minimum emissions standards is £12.50 for cars, smaller vans and motorbikes.

Lorries, buses, coaches and heavy vans that are non-compliant are charged £100 under the separate low emission zone scheme, which already covers most of London.

– How do I avoid the fee when driving in the zone?

Ensure your vehicle meets the minimum emissions standards.

For petrol cars that means those generally first registered after 2005.

Most diesel cars registered after September 2015 are also exempt from the charge.

– When does the Ulez operate?

All day, every day, except Christmas Day.

– How soon after a journey do I need to pay?

You have until midnight at the end of the third day following the journey.

– Where does the money go?

TfL says all revenue is reinvested into running and improving the capital’s transport network, such as expanding bus routes in outer London.

– What happens if I do not pay?

You may receive a penalty charge notice of £160, reduced to £80 for early payment.

Does it work?

There is good evidence that the policy so far has had a positive impact. In the first 10 months of the central London Ulez, road transport nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions fell by 35 per cent in the zone, and CO2 emissions by six per cent.

A study by Imperial released in February this year found that the expansion of the scheme to the north and south circular had also had an effect. It found that NO2 levels were 46 per cent lower in central London and 21 per cent lower in inner London than they would have been without Ulez.

This was achieved by having 74,000 fewer qualifying vehicles driving in the zone, a cut of 60 per cent since expansion in October 2021.

So what's the problem?

Critics of Ulez argue that it is unfair. They say that with the cost of living stretched, it is a bad time to extend an extra charge.

What's more, they say because the worst polluting cars tend to be older, the charge falls on lower income drivers who are less likely to have replaced their cars recently.

And they say the Greater London scheme is different to the inner London scheme because public transport is not as good as it is in inner London or the centre – meaning people have fewer options to switch to.

Is this fair? It's certainly true that people on higher incomes will be less bothered by a £12.50 charge than someone in lower income. There may also be something in the idea that lower income drivers have older cars.

But there is more context to be aware of. Defenders of the scheme point out that while lower-income drivers may have older cars, lower income people in London are in fact significantly less likely to have a car at all in London.

TfL has also allocated £160m million of its budget for a scrappage scheme to help replace polluting vehicles. This pays out £2,000 to any Londoner wanting to scrap a non-compliant car and can even come with other perks like free bus passes. The money does not have to be spent on a new car.

Is Ulez unpopular?

Overall, despite the coverage the campaign against Ulez has managed to generate, the policy is actually rather popular in London.

Most polls have found similar results: the latest, by Redfield and Wilton, found 47 per cent of Londoners back expansion to the whole of Greater London, with 32 per cent opposed.

Drilling into the data, there is some variation: if you only look at people living in the city’s outer boroughs – where the scheme is being expanded to – people are evenly split, with 39 per cent responding each way. But this is far from a universally unpopular policy.

One caveat that could explain the spirited -anti campaign is that many may be located outside London. If you look at where people signing anti-Ulez petitions live, huge numbers live in the home counties.

This makes sense: these people are affected by the scheme if they wish to drive into London. Fortunately for Sadiq Khan, they do not have a vote in London elections – which may explain why he is confident about pushing ahead with the policy.

Is this fair? People will have different answers. On the one hand, people outside the capital are affected by a policy they have no say in. On the other hand, people in London were never consulted on whether they wanted to breathe poisonous aid caused in part by people who don't live there.

It’s also worth noting that this picture of public opinion is a snapshot. There is good reason to think that a few weeks before the implementation of a scheme is the most unpopular we’ll ever find it: give it a few months and people will have new cars or travel patterns to avoid it. Given it's pretty popular already, that's good news for Sadiq Khan.

This is one reason the mayor doesn't want to delay: why take the hit just before an election, when you could implement it now and make it less of an issue in a year's time?

Why has Keir Starmer attacked Ulez?

All this being said, why is Sadiq Khan taking friendly fire from the Labour leadership over Ulez?

It all goes back to Labour's failure to win the Uxbridge by-election. Keir Starmer and his allies have blamed Ulez for the result: Starmer said the mayor should "reflect" on the scheme and refused to endorse it, while the losing candidate said it was a "bad policy".

Why the rift? The main thing to remember is that Sadiq Khan and Keir Starmer are targeting different electorates. Khan's concern is what Londoners think of him, because he is mayor of London.

For Starmer, however, London is frankly not important. If the polls are right, Londoners will vote Labour anyway at a general election, and there are only a few marginal seats he could pick up in the capital on a really good night.

Uxbridge is not like the rest of London. It is a wealthy Tory seat, and one where 80 per cent of households have access to a car. Across the whole of London the figure is more like half, with significantly lower levels of driving in the inner boroughs.

But while the result is not representative of the capital, team Starmer is calculating that it resembled other constituencies they want to win across Britain.

Nevertheless, going after the flagship policy of Labour's most senior elected office holder is certainly an unusual approach. It may be that Starmer's approach pays off and neutralises a Tory attack line at the election. On the other hand, it could play into the perception that he stands for nothing and tells people what they want to hear.

Are there any other schemes like Ulez?

Ulez is the most ambitious clean air scheme in the UK, but it is not entirely unique.

Birmingham's Clean Air Zone (CAZ) has similar rules to Ulez, and been going since 2021. It covers all roads within the city's ring-road, with a charge of £8 for polluting vehicles.

Bristol also introduced a £9 scheme in 2022 covering part of the city centre, while Oxford has a tiny scheme covering just nine streets. There are also a variety of weaker schemes which only cover commercial vehicles, such as the ones in Bradford, Portsmouth and Bath.

One major city missing from this list is in Manchester, which was due to implement a CAZ from May 2022. Mayor Andy Burnham abandoned the scheme under political pressure, and the policy is now under review. It has been suggested the plan could make a come-back in a lesser form, perhaps excluding private cars.

Ulez is already the biggest of these schemes, but when it covers the whole of Greater Londoner what will really set it apart is its sheer size.

Looking ahead

Given the noise about Ulez it might feel like a major, permanent change: but it could actually be quite temporary. As cars are replaced, fewer will have to pay and the scheme could end up eating itself. TfL's own projections show Ulz raising revenue in the first year, but with that cash falling off quickly as people replace their vehicles to comply.

So the mayor could be having a big political fight over something that doesn't last very long. In the long term, TfL wants to replace Ulez and the congestion charge with a more comprehensive "smart road charging scheme" to reduce traffic – though we don't know what this would look like yet.

If this doesn't happen, another way of updating Ulez for the future might be to raise the emissions standards cars have to comply with.

Either way, one thing is for certain - the expanded scheme is coming in on Tuesday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments