Tories identify eight groups of voters as Labour look to Obama campaign for inspiration: The sophisticated tools that rivals hope will win them 2015 election revealed

Where once there were door-knockers and pamphleteers, now there’s ‘segmentation’ and demographic database. Archie Bland profiles the methods

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You may think you are a complicated person, with considered opinions, instincts and values that come together to form a unique character. And perhaps you are right. But you are something else, too: you are a voter.

As a voter, for a long time, you have been depersonalised, and categorised, in crassly alliterative ways. You might have been Mondeo Man or Worcester Woman or one of the Pebbledash People. As such, your proclivities towards one party or another have been scrutinised by political analysts for clues about who will run the country.

In the past, those categories have been relatively simple, and the groups granted the mysterious power to decide elections confined to a very few. “It used to be that all you could do was deliver a leaflet or a piece of direct mail,” says one senior Labour strategist. “With a blunt instrument, you only need a blunt understanding.”

The political rhetoric is still pretty blunt: whether it’s Ed Miliband talking about the “Squeezed Middle”, David Cameron talking about the “Strivers”, or Nick Clegg talking about “Alarm Clock Britain”, each party leader is making a soundbite pitch at the same broad group.

Behind the scenes, though, things will be different this time around. The complex demographic tools that were already playing an important role in the 2010 election have reached new heights of sophistication, and the battle for supremacy in this vital part of the political war – “segmentation” – is well under way.

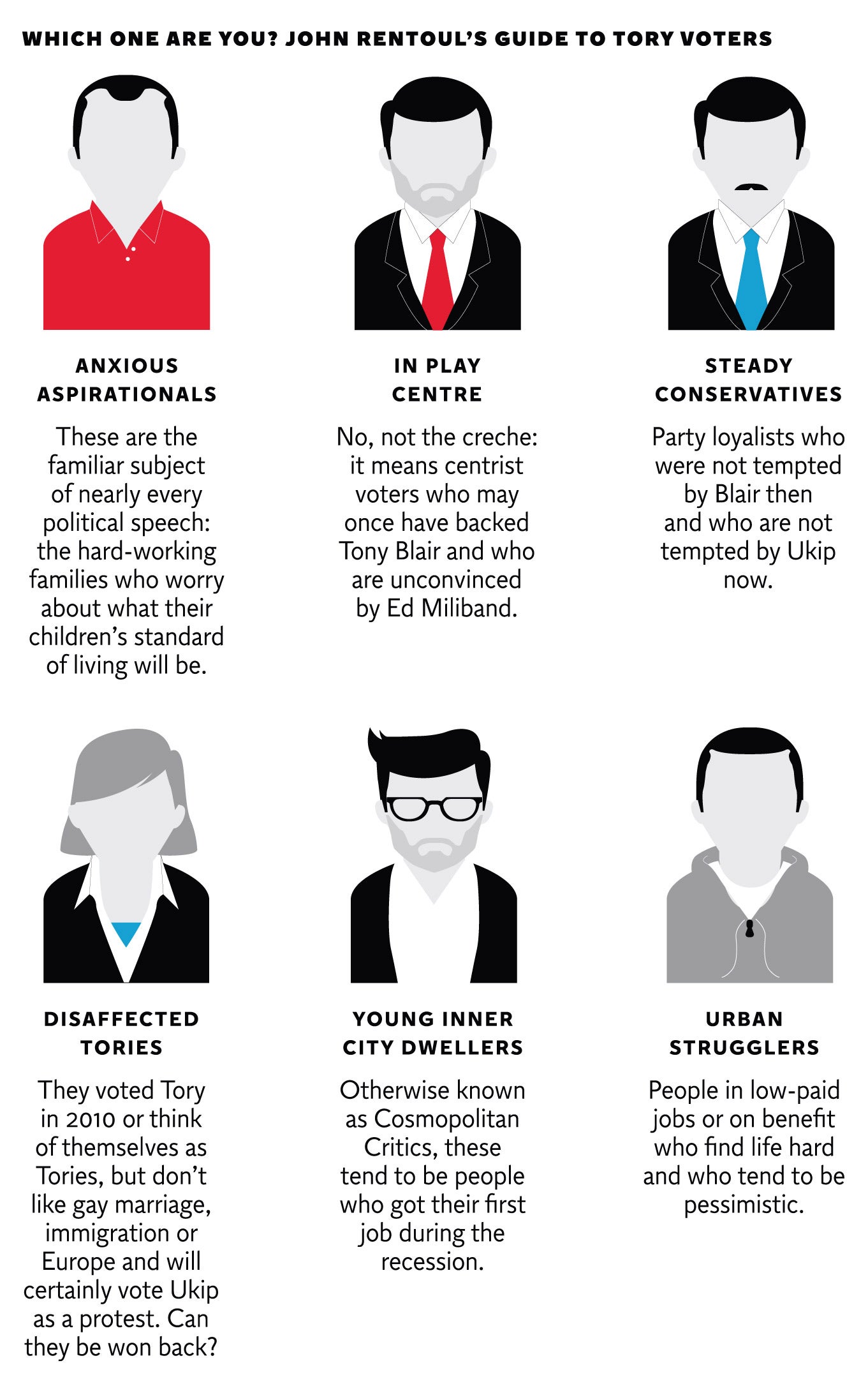

Earlier this week, The Times columnist Rachel Sylvester revealed that the Conservatives have identified eight key groups of voters to target. Although Downing Street quibbles with some of the names, from the Anxious Aspirationals to the Disaffected Tories, the pen portraits add up to a subtler version of Britain in 2013 – and in particular of the swing voters in battleground seats who will decide who wins power.

Each of these groups, the Tories believe, will be vitally important to building the coalition of interests that will help them win the next election – and each one will be persuadable of the case for David Cameron only if they are targeted in the right way.

The tools at the strategists’ disposal for winning them over are all based on one crucial, if overused, phrase: big data. One computer programme considered essential to the modern electioneer and used by all three main parties, Mosaic, assembles up to 400 pieces of publicly available data about each voter to put them into one of 15 main groups, or 89 hyperspecific categories, from “corporate chieftains” to “golden empty-nesters”.

“You’ve always had these segments that people want to win over, but what’s different now is that you’re finally able to develop a typology of the electorate,” says Rick Nye, managing director of the polling and strategy consultancy Populus. “You’re beginning to be able not just to identify those types of people but also to be able to pick them out from the general population and communicate with them on a personal basis.”

All of this adds up to a big leap forward for Team Cameron. Despite its increasing sophistication, though, and significant new hires – including Andrew Cooper, formerly of Populus, as director of political strategy – there are persistent fears that the Conservative operation is starting at a handicap. “We know that Miliband is putting huge amounts of effort into this,” says one senior Tory. “[Labour] has really studied it. The danger is that we are looking at the board and assuming broad parity without looking at what’s happening underneath.”

Indeed, while Labour still retains elements of that segmentation model, one which it was already using in 2010, it has looked to the Obama campaign for inspiration and has even hired one of the President’s mentors, the community organiser Arnie Graf.

This time around, Labour insiders say, segmentation is being left behind as a relatively crude system that fails to take into account just how various voters are. You might, it turns out, be allowed to be a complicated person after all.

“The stuff the Tories are presenting as innovative we have been doing for a long time,” boasts a Labour strategist. “But we’re trying to move beyond simple segmentation towards a much more sophisticated, individualised model.”

When all of this is put together, it suggests that the truly decisive factors in the next election are unlikely to be the debates over leadership or party unity that so dominate the media cycle. “I do feel like Westminster politics is just looking at the bit of the iceberg above the water,” says the strategist. “All the focus on the air war is missing the ground war, where this is really going to be won or lost.”

Maybe the key text in the theory of 21st-century electioneering has been Microtrends, a 2007 book by Mark Penn, a hugely influential US pollster. Penn was the man who helped Bill Clinton win power by identifying “Soccer Moms” as a key demographic, and later was chief strategist when Hillary Clinton ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008.

Penn argued that America was moving away from broad social movements and towards a far more complex set of narrower interests, each of which needed to be spoken to on their own terms. He identified all kinds of subgroups, from “30-winkers” (people who don’t get enough sleep) to “Pro-Semites” (gentiles who want to go out with Jews).

In the end, the application of the Microtrends model to the Hillary Clinton campaign failed. Some saw that defeat as a sign of the significant limitations to this whole approach. “It fell down as a narrative against Obama’s ‘Change’,” says the senior Conservative, who sees these tools as a powerful means of working out whom to talk to, but not of what to say to them.

“Politics is still at heart an emotional appeal. Plus, in the age of social media it’s very hard to demarcate information to specific groups like that – to tell entrepreneurs one thing and single mothers another. With digital, these messages are bound to bleed across.”

Still, as a means of engaging voters who might not otherwise pay attention, Penn’s theory seemed like a vital insight to many political operatives. “You need to understand who different voters are, and what messages they’re susceptible to,” says Andrew Hawkins, chairman of ComRes. “You can’t just focus on the psephological question of numbers on the ground.”

Those eight Conservative target groups amount to a theory of how to win the next election. They will be approached using Mosaic, an enormously sophisticated demographic database that has been a central part of all three parties’ operations. (Insiders say that Conservatives, relatively slow to exploit its capabilities in 2010, are working hard to build links with the company who built the system, Experian, in advance of the 2015 race.)

So, how does Mosaic work? “A political party will plug in information they have about their supporter base,” explains Bruno Rost, a spokesman for Experian. “They will do this across a very large database, and from that they will map out where and what type of people their base is – and more specifically, what issues they’re interested in. From that, they can target specific communications, depending on whether, say, someone is a key supporter or a floating voter.”

The system can also help identify whether someone is best approached by email, phone or in person.

This system helps strategists to craft messages not according to the crude old measures of class, age and location but by taking into account factors that may give a much more potent psychological insight into a voter’s interests. It makes an election machine massively more efficient. But it has limitations. Many people will belong in more than one category, and it isn’t necessarily easy to define which of their demographic particulars tell you most about their interests.

Ben Page, chief executive of Ipsos Mori, points out that Google claims to tailor its ads according to the most sophisticated algorithms but still gets it wrong about a quarter of the time. “You can deliver a jarring message because you’ve got the segmentation wrong,” he says. “So an old person who lives in a block of hipsters is getting a message about the council installing new bike racks. There is a risk. I mean, I occasionally buy cat stuff for my mother on Amazon. Now every time I go on there, it’s like a pet store.”

This may simply be the cost of doing business – the occasional misdelivered message that leaves the recipient shrugging. But it can be much worse. Unnervingly, Mosaic is able to identify likely cancer sufferers using anonymised hospital statistics; in 2010, Labour came under fire for sending cancer patients cards warning that a Conservative government would put their lives at risk. While it denied that the recipients were identified as being likely to be ill, the story makes the dangers clear.

“There’s a higher expectation of political parties using this approach than businesses,” says Ruth Fox, head of research at the Hansard Society. “The more micro the segmentation, the greater the risks that you send a letter that is of no relevance but implies personal knowledge.”

With these limitations in mind, Labour began to craft its approach to the next election – building on Mosaic with another, arguably even more sophisticated tool. Nationbuilder, which showed its potential in the SNP’s stunning victory in the 2011 Scottish Parliamentary elections and came of age as a key tool of the Obama campaign in 2012, is pretty simple – a bundle of software that brings a range of vital functions of the modern political operative, from planning events to sending out mass emails to whipping up support on Facebook, into one seamless whole.

By linking these functions, it makes it easier to see which Twitter follower might become a party member, and which might even organise an election-day event. The Conservatives may yet embrace it; one recent Telegraph piece warned that the failure to do so could cost them the election.

Labour certainly hopes so. It sees its crucial advantage as being a newfound ability to move beyond segmentation. “What we’re able to do now is identify key drivers of what makes someone vote Labour,” says the senior strategist. “So rather than saying there’s this big group of middle-income mums, you’re able to really treat them as individuals.”

Let’s say, for example, that a voter is a middle-income mum. Labour might have identified her as living within a small radius of a Sure Start centre that could be closed, and sent her an email telling her so. In 2010 it might have ended there. But now, if she doesn’t open the email, the party will know about it, and adjust its approach accordingly. And if she subsequently opens a Labour email about rising energy prices, or even sends a reply, the set of messages she will receive will subtly change.

“You build up a more sophisticated picture of what they’re interested in. And our experience is that the more personalised it is, the more warmly people respond.”

The overall picture is of an election that will be more personalised than ever before. Some warn that this will also mean it is more invasive – and perhaps bad for political discourse. “I don’t think highly targeted literature sent to a portion of the population who live in swing seats is necessarily good,” says Ruth Fox. “It’s obviously an effective tool for the parties, but it’s questionable whether it’s good for long-term engagement.”

Others suggest that, even if the means rely on data that most of us barely even realise is available, the end is a good one: an election battle where people hear about the things that matter to them more than ever before.

“This approach is really just recognition of something voters have known for a long time,” argues Rick Nye. “Voting is an exercise in self-expression as much as in self-interest. Now we’re getting beyond simple class identity or self-interest and looking at values, attitudes and outlooks. It’s a sign that politicians are beginning to understand it’s not about them. It’s about the people who elect them.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments