The In/Out Question: Why Britain should stay in the EU

European elections are weeks away, the Clegg-Farage TV debates are about to kick off, and there's a huge question mark over Britain's place in the EU. But, says the author of a new book, the case for staying in has never been stronger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Should Britain quit the European Union? Or should it stay? What, indeed, would quitting mean? The hard-line eurosceptic view can be summarised in three phrases: our plight is dire; attempting to reform the EU is futile; the prospects outside are golden. My view is the opposite: our existing EU membership is valuable; we have a great chance to make it better; and all the alternatives are worse.

Indeed, it would be a historic error to pull out. Our economy would suffer if we quit. Our global influence would also be diminished.

The UK now accounts for less than 1 per cent of the world's population and less than 3 per cent of global income (GDP). Each year that goes by, these numbers shrink a little. We will find it increasingly hard to get our voice heard on topics that affect our prosperity and well-being if we go it alone.

Of course, there are problems. Just to list a few: the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is a waste of money that keeps food prices higher than they would otherwise be; its regional policy splurges money on unnecessary motorways; the EU often meddles in things that are best left to nation states – such as the hours people are permitted to work and how curvy cucumbers are allowed to be; the European Parliament seems like a travelling circus, shuttling back and forth between Brussels and Strasbourg; and EU regulations are sometimes heavy-handed.

There is also a lot that is good within the EU. First and foremost is the single market, which gives British business access to the entire EU with its 500 million consumers. Free trade is one of the most powerful ways of boosting wealth. We would be foolish to compromise our access to this market.

Contrary to popular belief, EU membership doesn't cost us much, either. Our annual budget contribution, after taking account of money transferred back to the UK, is £8.3bn. That's around half a per cent of our GDP, or £130 per person.

When the Confederation of British Industry surveyed its members in 2013, it found overwhelming support for Britain to stay in the EU among both big and small businesses: 78 per cent wanted to stay versus only 10 per cent wanting to quit. Three-quarters thought leaving would have a negative impact on foreign investment in the UK.

At the moment, when we negotiate with America, China or Japan, we are doing so as part of the world's largest trade bloc, which accounts for nearly 20 per cent of world GDP. Washington, Beijing and Tokyo have to take Brussels seriously as a trade partner. If we were on our own, the balance of power would be quite different. The US economy is seven times as big as ours, the Chinese is five times as big, and Japan's is twice our size.

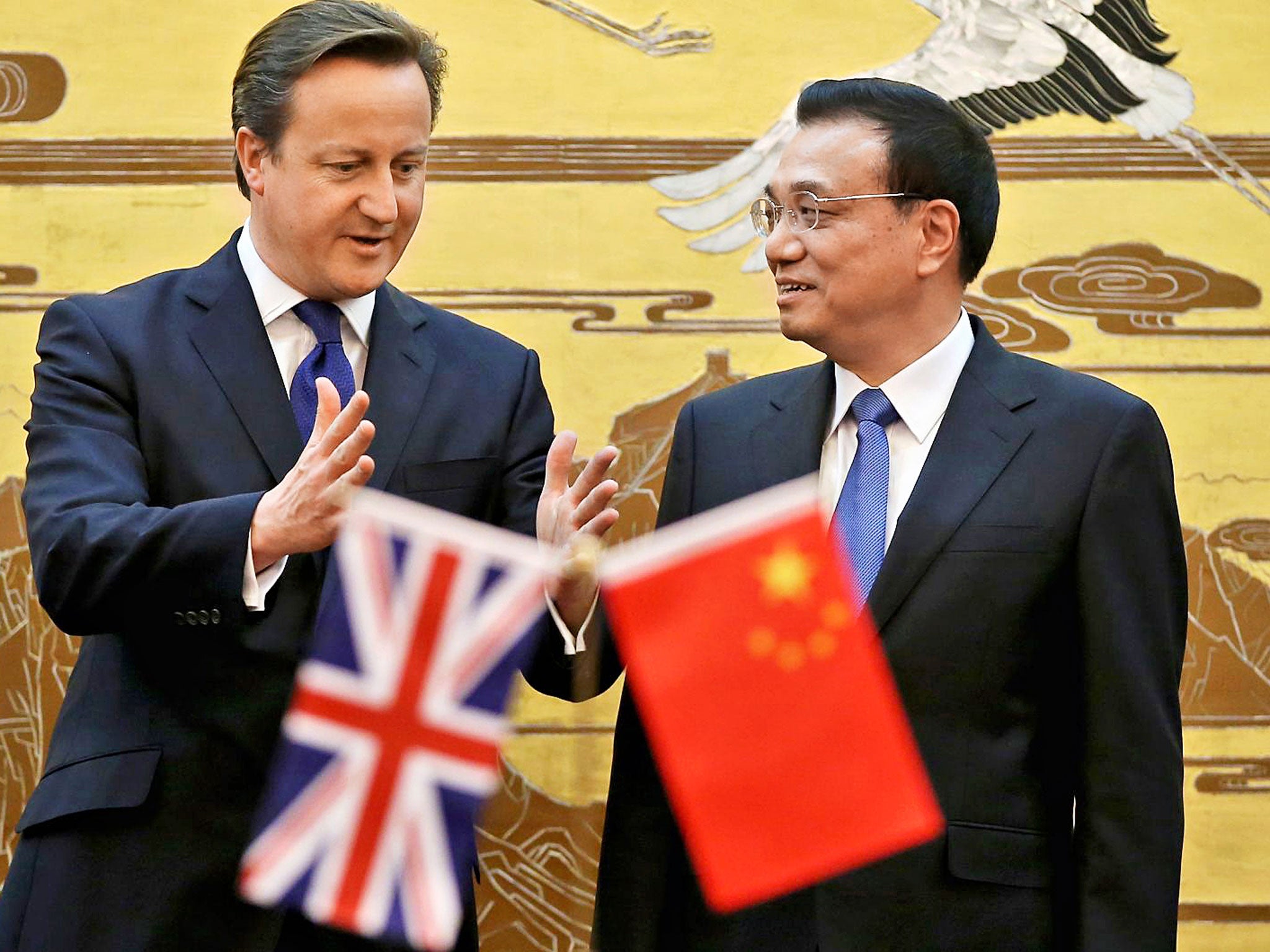

It is telling what a Chinese government-controlled newspaper, the Global Times, said about Britain when David Cameron visited the country in 2013: "The Cameron administration should acknowledge that the UK is not a big power in the eyes of the Chinese. It is just an old European country apt for travel and study."

If we left the EU, we'd often find ourselves opening up our markets more to the world's big economies than they would open theirs to us. We'd typically have to play by their rules – whereas, at the moment, we influence the EU's product regulations, which then have a chance of becoming global standards. We'd also have to negotiate with the EU, whose economy would be six times our size after we quit. Far better to stay in the EU and use its influence to open up markets elsewhere.

The single market is based on what are known as the "four freedoms". These were contained in the Treaty of Rome that set up the forerunner to the EU in 1958: the free movement of goods, services, capital and people. This is one of the most important charters for freedom the world has ever seen.

In Britain, there is little controversy over the first three freedoms. But the free movement of people is the subject of heated debate. Indeed, a desire to keep foreigners out of Britain is the main reason why the electorate may want to quit the EU entirely.

Immigration is undoubtedly an emotive topic. But allowing free movement of people within the EU has been good for our economy. It has also enriched our culture and given our own citizens more opportunities to work, study and retire across the Channel. Hundreds of thousands of our citizens work in other EU countries; hundreds of thousands more have retired to sunnier climates around the Mediterranean. There are one million Brits living in Spain, 330,000 living in France, and 65,000 in Cyprus. There are also 330,000 in Ireland.

If we left the EU, it is not at all clear what would happen to our citizens living and working abroad. But the best guess is that tit-for-tat would prevail. In the unlikely event that relations got really acrimonious and we kicked EU citizens out of the UK, the EU would probably retaliate and kick out our citizens, too. That would be disastrous. More likely, we would just severely curtail new immigrants crossing the Channel to Britain. But if the EU then stopped Brits going to live and work there, that would still be a diminution of the freedom we currently enjoy.

Now look at the EU citizens living in the UK. Most are young and skilled. They come here mainly to work. Their so-called "non-activity" rate – which covers pensioners, students and stay-at-home parents as well as the unemployed – is 30 per cent. The rate for the UK population as a whole is 43 per cent. Meanwhile, 32 per cent of recent arrivals have university degrees compared with 21 per cent of the native population.

Many Brits are worried about EU immigrants taking our benefits. The facts, though, don't bear this out. European immigrants are half as likely as natives to receive state benefits or tax credits, according to a study by academics at University College London.

The average age of the European immigrant population in Britain was 34 in 2011, compared with 41 for the native population. We don't pay much for the immigrants' education since they normally arrive after being educated. And, since most of them are of working age, we don't pay much for their pensions or healthcare, either. Many eventually return home, carrying good memories of the UK with them. In other words, we get a good deal from EU immigrants.

In judging the merits of EU membership, we should look at the future, not just the present. In particular, can we make it more competitive and less centralised? The crisis in the eurozone and rising euroscepticism throughout the EU mean we are well placed to do this.

This argument, it has to be admitted, is contrary to the conventional wisdom that the eurozone will have to integrate further to solve its problems. Germany, France, Italy and the other countries will then act as a single bloc, with the ability to dictate what happens in the EU without taking account of our interests – even on matters that are vital to us such as how the City is regulated.

But the eurozone probably won't rush towards so-called political and fiscal union. The growth of euroscepticism across Europe means the elites won't be able to bamboozle the people into agreeing more transfers of power to Brussels, as they have done in the past. Political union is also unnecessary because the main problem with the periphery is one of competitiveness. Centralising power and giving hand-outs won't solve that. The solution, rather, is to restore competitiveness and boost productivity by freeing up markets. This is not a pleasant process, but it is beginning to happen in places such as Greece and Spain.

The peripheral countries have to solve their own problems. But the EU can help in four ways: it can complete the single market in services, which is patchy; it can open up Europe's markets to trade with other parts of the world, especially the United States and China; it can help develop a modern financial system based more on capital markets rather than banks; and it can lighten the burden of regulation on business by cutting red tape.

The euro crisis is an opportunity for Britain, because all these things would be beneficial for our economy. Just think how Germany is the big winner from the single market in goods because of its prowess as a manufacturing nation. Extending it fully to services, where Britain excels, could be correspondingly beneficial for us. Or think about what would happen if the EU was less "bankcentric" and relied more on capital market instruments, such as shares and bonds, to channel funds from investors to companies. The bulk of the business would flow through the City of London with its army of investment bankers, lawyers and accountants. More trade and less red tape would help our businesses, too.

The time is ripe to persuade the EU to sign up for such an agenda. Germany's Angela Merkel made clear on a visit to London in early 2014 that she saw Britain as an important ally to make the EU more competitive and less bureaucratic.

In determining whether to quit the EU, we shouldn't just look at the benefits of being in, but also understand what "out" would mean. None of the varieties would be attractive.

Let's start with the option of staying in the single market. That may be feasible. After all, Norway has access to the single market without being in the EU. This means it isn't part of the CAP. But there is a big disadvantage: Norway has to apply all the rules of the single market without any vote on what those rules are.

If Britain was in the same position, it really would be subservient to Brussels. Quite apart from the blow to our sovereignty, the rules would be written without taking account of our interests and so could easily harm us. It's hard to see how such an arrangement could be preferable to our current membership.

Because the Norwegian option is unappealing, many eurosceptics cast around for half-way houses that give some access to the single market but without following all the EU's rules. The two main ones are Switzerland and Turkey. Unfortunately, they don't have full access to the market and they still have to follow some of the rules, without a vote on them. If we copied them, one consequence is that the financial services industry, which accounts for 10 per cent of our economy, would lose its "passport" to offer services across the Channel.

Other eurosceptics think we should rely on our membership of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to ensure access to markets. The snag is that, although the WTO has made progress in opening up trade, it has not secured anything like free trade in manufacturing – let alone services, which account for more than three-quarters of our GDP. Our large car industry, for example, would have to pay 10 per cent tariffs on exports to the EU. No wonder Ford warned in early 2014 that the UK would be "cutting off its nose to spite its face" if it quit the EU.

Investment would fall as foreign companies that invested in the UK as a launch-pad for serving the entire EU market shifted some of their activities across the Channel. Some British companies would do the same. Unemployment would rise until wages had fallen far enough for people to price themselves back into the market.

There are no good alternatives to membership. We should stay in the EU and put our energy into reforming it. We should fix it, not nix it.

'The In/Out Question: Why Britain should stay in the EU and fight to make it better', by Hugo Dixon, is published as a Kindle Single (Scampstonian, £1.99), available at http://amzn.to/Q7xImP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments