The Highland Clearances and land reform in Scotland: The country's semi-feudal great estates face reform

Scotland's vast estates were created on the misery of crofters and clansmen by a treacherous elite in league with the English. Ben Judah meets the land-grab rebels who want action to be taken.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They call him the Mannie, and panting, almost out of breath, I can see him rising over the dying bracken and the dry gorse at the top of the hill – a sandstone giant, atop a 100ft column of colonial splendour. This is the first Duke of Sutherland, and tiny beneath his plinth, here since 1836, I can see where Scottish Nationalists have been digging to topple him.

The Victorians called him the Great Improver. The towering Duke was English, of course, and everything you can see from this peak, from the mountains in the distance, to where the coast disappears out of sight, he inherited with his Scottish marriage. This was, and much of it still is, the Sutherland Estate, the barren result of the Duke's improvements – the Highland Clearances. Deer skip and chew through lichen and tufts, where his men burnt whole villages, as the hill tumbles into the sea.

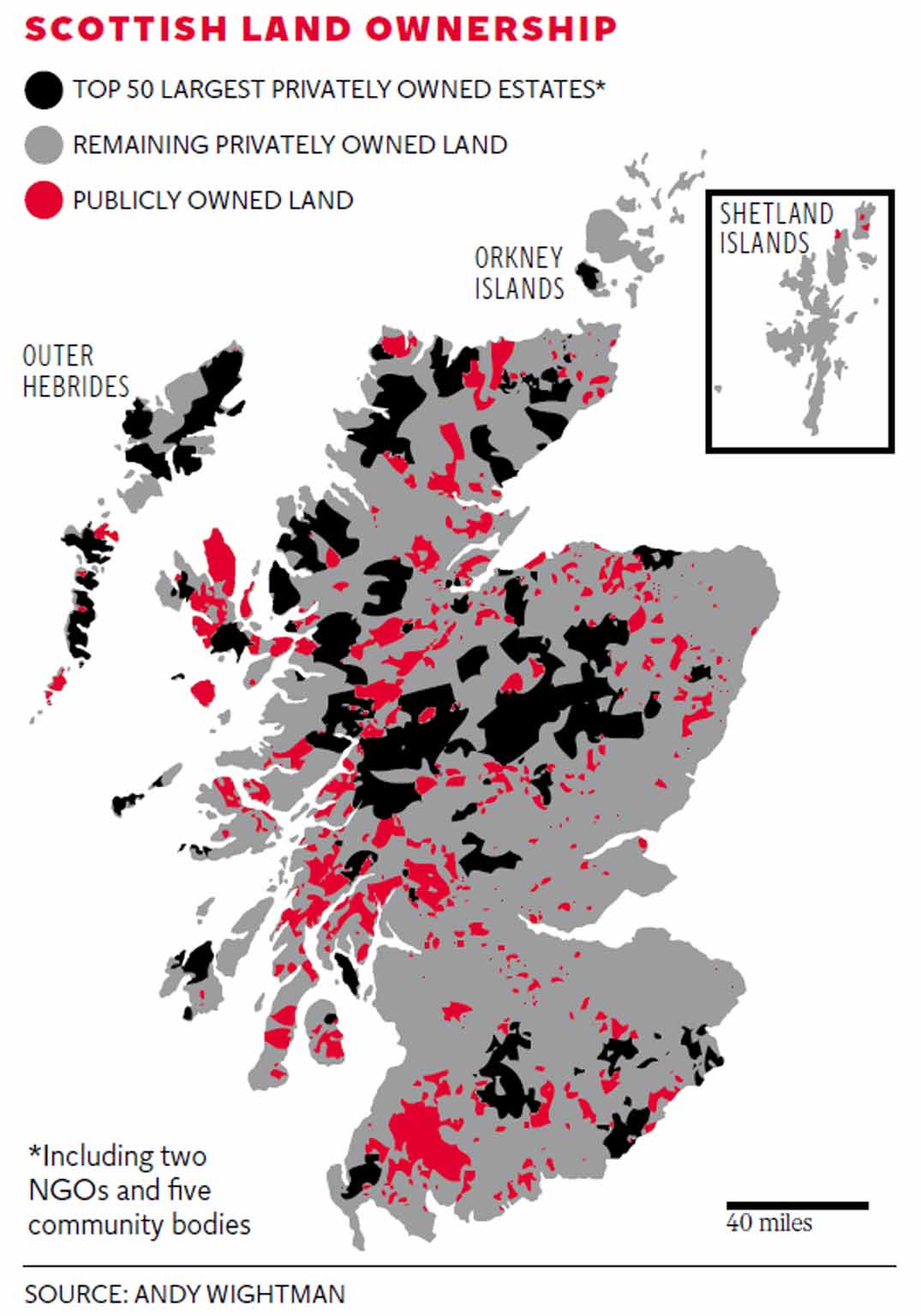

The Highlands as we know it is still a patchwork quilt of enormous estates created out of the Clearances. Today half of the privately owned Scottish countryside still belongs to 432 landowners. Nationalists call this a colonial creation, and radicals inside the Scottish National Party are pushing Holyrood to begin dividing them up.

Hunger for land reform has grown in the Highlands alongside nationalism. The attacks on the Mannie began in the Nineties. At first, there was a plot to dynamite it. Then, in green paint, they daubed “Monster” all over him.

SNP politicians in Inverness began hectoring for the Duke to be ripped down and replaced with a Celtic cross. Nationalist intellectuals suggested breaking his column, and then smashing him limb by limb, to lie ruined like the torched crofts of his 15,000 evictees. The closer Scotland gets to independence, the closer the Mannie, and the estate system he symbolises, is to a full-frontal attack.

What were the Highland Clearances and why do they matter? The barren moors as we see them today are a modern, man-made wilderness. After the Jacobite rebellions, Scotland's feudal lairds, who once saw themselves as clan chiefs, protecting upland villages, evolved into 19th-century British lords. Their inheritance was overpopulated, unprofitable and blighted by disease. To turn a profit, men like the Duke of Sutherland believed they knew the answer. They would empty the hills, forcibly resettling their tenants. Sheep, and profits, would replace people. Eviction would be swift and villages would be set alight if they resisted. Those who could not be resettled on the coast would be sent to the colonies. Two centuries on, the sheep have gone. The bracken and the heather are now grouse moors and deer forests, filled with the childhood memories of the aristocracy.

There used to be a “British” narrative to these events: in 1707 a poor Scotland and a rich England fused, with the result that Highland families rushed to work in the spectacularly industrialising Lowlands, and destitute crofters set out to conquer and colonise the world under the Union Jack. The Highlands, went the old reading, had been improved from misery into thriving sheep farms and grouse moors, with the people packed off to new, better lives in Canada and other thriving white colonies.

In 1973, a radical theatre group toured the Highlands. Called the 7:84 company (because seven per cent of Scotland's population owned 84 per cent of its land), they were performing a play by John McGrath, The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil. The church halls were packed. The Highlands, the story went, had not seen any improvements. In fact, it had been a colonial frontier. Treacherous lairds, conniving with London money, had expelled their own people from the lands. Then they ruthlessly exploited them: first the stolen moors had become sporting estates, and then came the fire-belching oil-platforms of the North Sea. The play was an instant sensation.

The following year, a radical, little-known theorist called Tom Nairn published a book – The Break-Up of Britain – which was sniggered at in London as fantasy. It is now seen as a milestone in Scottish writing.

Nairn argued that Britain was nothing less than an old, aristocratic, imperial state; a decrepit thing holding back democracy. To a new generation in Glasgow and Edinburgh it felt bang on. And along the coast road, a few miles north of the Mannie, I find that a new history is being erected in Scotland.

Here is the village of Helmsdale, all shuttered shops and pubs, where Alex Salmond came in 2007 soon after becoming Scotland's First Minister. At dusk, bluish lights from oilrigs blink from the sea as I stand by the SNP's anti-monument: The Emigrants. This is dedicated to those driven out of the hills by the Duke of Sutherland. A bronze couple and their children, evicted to lives overseas, the father looking forward, the mother looking back into these tumbling hills of pleasure-shooting with hate. The book, the play and the statue all tie together – into the emergence of a new popular mythology, replacing at its heart Britishness with the Clearances. It is Scotland reimagined as a second Ireland, England's victim, not England's partner.

When they free Scotland, SNP activists dream they'll free the hills – and in Highland pubs, I find the land-reform dreamers. Cleaners are planning to turn the grouse moors into national parks. Water-maintenance technicians are sketching out how to turn the gamekeepers into park rangers. On the road to Inverness, in one hamlet after another, is SNP militancy.

In the Highlands, I find dreamers everywhere, even in the ski resort of Aviemore. Before the referendum, a couple of crusty old folk would meet as the SNP, but since then the party in the area has swelled from 60 to more than 260. This is happening everywhere. There were 25,000 members before the vote; there are 115,000 now. This momentum, and the SNP's sweep of 56 out of 59 seats in last May's general election, is why two-thirds of Scots now think independence is inevitable.

Now party radicals want land reform to go further than has ever been expressed before: not only to make community buyouts impossible to resist, but to ban landowners leaving their estates to a single heir, breaking them up over time. And they want punitive taxes to force sales. They may not couch it in these terms – but they want Scotland to follow Ireland, where before independence more than half the country was owned by absentees in estates of 3,000 acres or more.

There is drizzle on the windscreen as we drive into the Cairngorms. My guide is an activist from the SNP, whom I'll call Alex. “Don't quote my real name, or put my job,” he pleads. “When you live in the country, lots of your work depends on these lairds. It's not just me, but the builders, the joiners, the electricians and gamekeepers. They're all SNP. They all want land reform. But you can't fall out with the laird – that's your job gone.”

We drive on, into the glens. But we are 40 years too late for the countryside, where the tenants who escaped emigration once lived. The villages are gone. One after another, in whitewash, all shuttered up. “That's a holiday home, that's a holiday home, that's stayed in, that's a holiday home, that's just been sold to be a holiday home.”

The acquirers, for the most part, are English. “We can't afford to live here any more, all these holiday homes have pushed the prices up to like £500,000 for one of these cottages and they've killed 'em off, all the shops.”

This means the Highlands look open, immense – but actually, for the people here, the little slivers where they really live are cramped and narrow. You can't build here, that's an estate. You can't build there, that belongs to the laird. It is hard to live here. Wages are a third below the Scottish average, but prices come out a third higher.

Alex begins talking about history, while I wonder whether all new nations must be based on victimhood. He explains that, when this or that fort was built in the 18th century, a quarter of those in Scotland spoke Gaelic and lived with their own clans and culture. Nationalists like him believe that from this ruin, beginning with the Jacobite rebellions, there is only one storyline that matters: the conquest of Gaelic Scotland. Lairds who fought the redcoats were executed, their land possessed by the Crown and gifted to loyalists. Gaelic dress and Gaelic schooling were forbidden and a way of life was finally broken in the Clearances.

“It's awful, just awful, what they did,” says Alex. But there is one crucial difference between the crushing of Ireland and the annexation of Scotland: betrayal. Unlike Ireland, Gaelic Scotland was broken by its own lairds – the clan chieftains once revered by tenants, now turned Westminster peers. When Queen Victoria was crowned, a fifth of Scotland spoke Gaelic; by her death, only five per cent, mostly in the Isles, still could.

Driving back in lowering gloom, I sit listening. “The SNP is not an ethnic nationalist party,” says Alex. “It's a civic one.”

Alex has been in the volunteer fire brigade. A few years ago, at 1.30am, their pagers had rung, bleeping, bleeping – emergency in the grounds. Panting, the boys ran and raced to the grand mansion. It was the laird's son. He was having a party. “And he was there, surrounded by all these bottles of champagne and he went, 'I've run out of water for my guests. Can you refill my tank?' The boys did it, and he gave them a glass of champagne, and a crate of beer. Those were the right sweepings off an Englishman's table, I tell ya.”

But that very same laird claimed an old clansman's lineage. This is why Scottish nationalism is not about blood. Scottish nationalists don't care if the ancestors of a Harrovian lord from the King's Road led the rebels' charge in 1745. We drive back to the real Highlands, a land of dismal bungalows, mini-roundabouts and co-ops, not turreted Victorian follies.

“That old laird, from the estate, we remember him, back in the referendum, he had his huge big poster: 'Delighted to be united', or whatever. But then six months later, he sold up. There were families living and farming there, and one day to the next, the new owner, some billionaire, went: 'Leave'. I tell you, it was like a new Highlands Clearances for them, it was.”

One farmer committed suicide when the old laird sold up and the new oligarch owner gave him notice to get out. “That family had farmed that land for three generations. The Clearances – the power to turf out families because you could – that's never stopped.”

Morning light. I am standing on the platform at Rannoch station, where in Trainspotting the junkies come for a breath of fresh air. A reddish wasteland ripples out from the platform into nothing. The deerstalker is waiting for me. We drive up to hunt with the guns.

“When they began, the SNP,” the stalker mutters, avoiding my eyes, “a lot of people thought they were good. To, you know, end the English rule. A lot of people liked it. A lot of people, they rise to them, against the English landowner. But now, we know they are going to interfere with our way of doing things, those of us up the hill don't like them at all.”

The stalker points down to Loch Rannoch. Most of the landlords here are now foreigners: Belgians, Swedes, Dutch, Germans. Further afield are Danes, French, Arabs. “The worst thing that could happen,” he says, “would be for the politicians in Edinburgh to destroy the lairds, who really are Scots, part of us for centuries, and hand this to some oligarchs. Or even worse, the politicians could destroy the sporting industry with an enormous and jobless national park.”

The rise of the SNP is unsettling the tiny rural communities around the great estates. Most of the people interviewed are too afraid to give their names. If they support land reform, they say they could lose their jobs. If they oppose independence, they say the local SNP would be aggressive down the pub. “They're so hotheaded, I say I'm not into this plan, they call me an English stooge.”

One landowner in Jura, who happens to be the Prime Minister's stepfather-in-law, has warned the SNP may bring about a “Mugabe-style” land grab. There is a sense of battening down the hatches. “We're a family. We've lived here for centuries. We know and love this village. We care. But if they decide to tax us till the pips squeak, a new community land trust won't pop up – but some sheikh who won't give a damn,” is a common refrain.

Like everyone in Scotland, the landowning families around Loch Rannoch don't know what direction the swollen ranks of nationalists are marching in: “British politics is so unstable. In 10 years they could be Scottish New Labour or they could be Scottish Sinn Fein.”

On the lochside, on a long tendril of land surrounded by darkening water and sky, it is easy to see Scotland in caricatures. The same goes for landowners. The majority of them live in Scotland, although the absentees are the ones with the greatest acreage.

Some of them have fortunes, others are clinging on. Some only come to Scotland for shooting on the Glorious Twelfth, while others, like Donald Cameron the Younger of Lochiel, who with 72,000 acres is one of the largest landowners in Scotland, have made their lives in Edinburgh. SNP activists do not see things in these shades.

Drained after the fog and the moor, I sit down and call Cameron. “The picture is much more nuanced than people would expect. Various people have set up this, I think, false argument: it's not private land equals bad, community landowners equals good. I feel part of my local community. I don't feel separate from them. These simplistic divides aren't there in real life. When you get to an estate you see a vibrant business that is employing local people and attracting them to the area. And were they not all tarnished with the brush of landowners, the SNP would be hailing them for their enterprise.”

Down the line, I tell the Younger of Lochiel what I've heard from Alex and others in the Cairngorms. “The history has entered popular myth,” he replies, “and there's no doubt that the Clearances are a great stain on our history and reputation. But at the same time, we can't be shackled by it. And that's my view. We are in 2015. And life goes on.”

On the night train heading south, as the windows shudder, I drift back to the two statues by the sea. Above all, I think, it is truly simple for The Emigrants and nationalist memory to win over the Duke of Sutherland and memories of Britain. The Scottish role in the conquest of India, and the Protestant mission, are not glorious stories any more. And in that absence, the Clearances loom largest.

A longer version of this article was originally published in 'Standpoint' magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments