The Big Question: Why doesn't the UK have a written constitution, and does it matter?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Because Jack Straw has used a visit to Washington to hint that Britain could finally get a written constitution spelling out citizens' rights and codifying this country's political system. The Justice Secretary is already working on a new Bill of Rights and Responsibilities, clearly defining people's relationship to the state, as part of a wide-ranging package of constitutional reform. But he has, for the first time, also said the Bill could be a step towards a full written constitution to "bring us in line with the most progressive democracies around the world".

Why don't we have a written constitution?

Essentially because the country has been too stable for too long. The governing elites of many European nations, such as France and Germany, have been forced to draw up constitutions in response to popular revolt or war.

Great Britain, by contrast, remained free of the revolutionary fervour that swept much of the Continent in the 19th century. As a result, this country's democracy has been reformed incrementally over centuries rather than in one big bang. For younger countries, including the United States and Australia, codification of their citizens' rights and political systems was an essential step towards independence. Ironically, several based their written constitutions on Britain's unwritten version.

What do our rights depend upon?

Britain's constitution has developed in haphazard fashion, building on common law, case law, historical documents, Acts of Parliament and European legislation. It is not set out clearly in any one document. Mr Straw said yesterday: "The constitution of the United Kingdom exists in hearts and minds and habits as much as it does in law."

Nor is there a single statement of citizens' rights and freedom. As the Justice Secretary put it: "Most people might struggle to put their finger on where their rights are."

What about the Magna Carta?

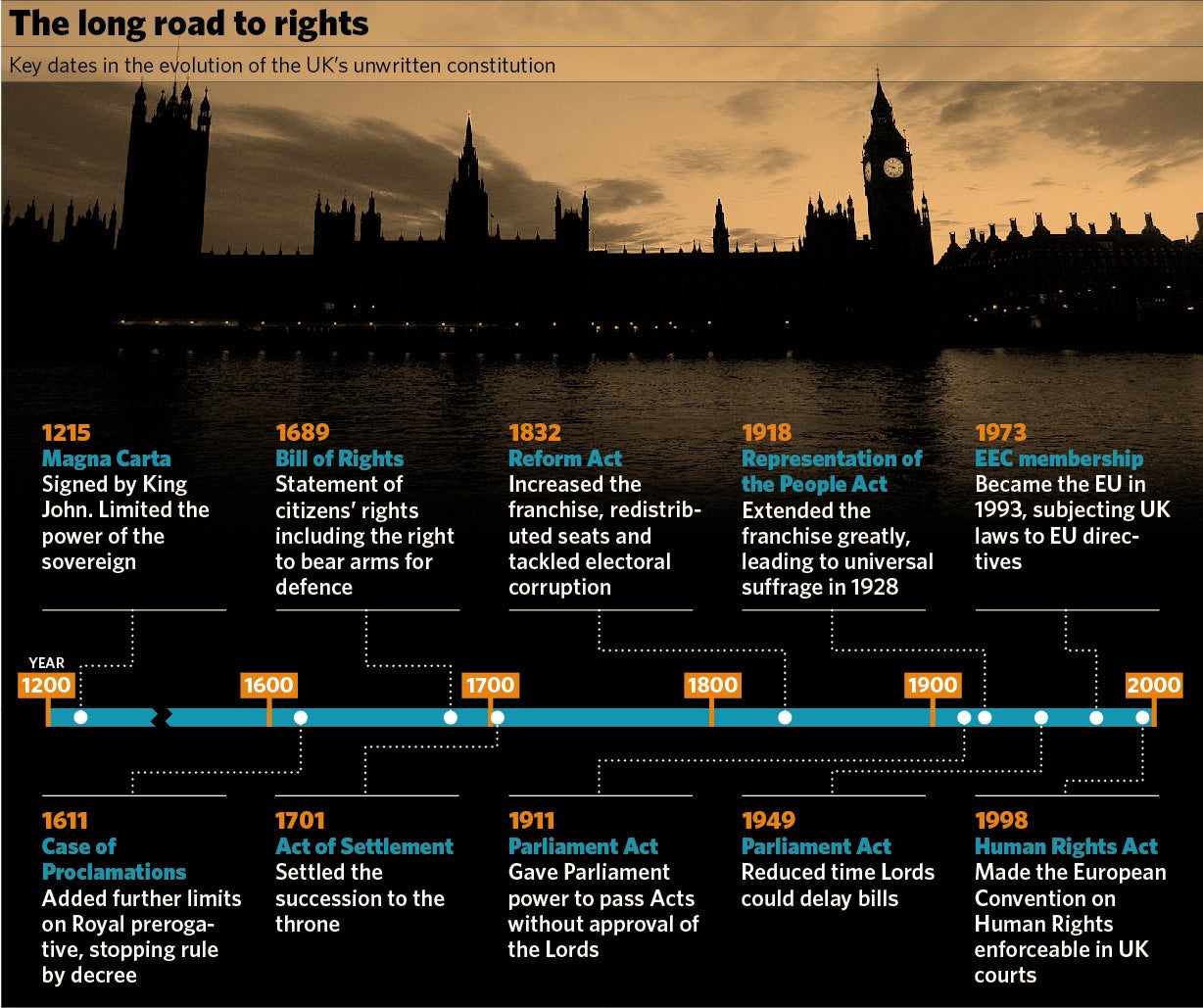

When the barons forced King John in 1215 to sign the Magna Carta, it was an event that would reverberate through constitutional law eight centuries later.

The landowners were driven by a desire to protect their own interests rather than those of the people. But the resulting document, which has no legal force today in this country, was a key inspiration for the architects of the US constitution.

It has had huge symbolic value in the development of Western-style democracy in that it limited state powers and protected some citizens' rights. Its key principles, including the right to a fair trial by one's peers and protection from unlawful imprisonment, have underpinned common law.

What other constitutional landmarks have there been?

The Bill of Rights of 1689, which followed the accession of William and Mary to the throne after the "glorious revolution" bolstered the powers of parliament and, by extension, the rights of the sovereign's subjects. They included freedom from taxes imposed by the monarch and from being called up in peace-time to serve in the army without Parliament's permission.

The Great Reform Act of 1832, which vastly increased the number of adult males entitled to vote in elections, is widely seen as the starting-point for establishing the sovereignty of citizens over parliament. It set in train the process that led to the Representation of the People's Act of 1928, which gave all men and women over the age of 21 the right to vote.

Then there was Britain's entry into the European Economic Community in 1973, which brought the country for the first time under a degree of international judicial control.

Ten years ago Britain came closer than before to codifying individuals' rights when the Human Rights Act enshrined the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

What are the advantages of awritten constitution?

It has become almost a truism that British politics, beset by cynicism about politicians and undermined by falling turn-outs at general elections, is in crisis.

Supporters argue that producing such a document could tackle such disillusionment, at the same time as setting new, clear limits on the power of the executive. The Liberal Democrats have called for the public to be involved in drawing up the constitution. They say: "This would reform and reinvigorate the democratic process, putting individuals back in control instead of the wealthy, large businesses and the unions."

And what are the disadvantages?

"It it ain't broke, don't fix it," argue opponents of a written constitution, who insist that the existing arrangements, however piecemeal their development has been, have worked well in practice. There are, moreover, formidable practical problems to be overcome before such a document could be drawn up. Would it be wide-ranging and largely abstract or would it list individuals' rights in detail and provide an exhaustive summary of Britain's constitutional settlement? If the latter, it could prove beyond the grasp of most of the citizens it would be designed to protect.

Why is the idea being floated now?

It is a natural follow-on from the proposed constitutional reforms announced by Gordon Brown as one of his first acts in Downing Street. He explained that he wanted to develop a "more open 21st-century British democracy which better serves the British people". As well as the British Bill of Rights, he suggested giving Parliament the right to approve any decision to send British troops to war and surrendering the prime minister's power to appoint judges and approve bishops. Such proposals would be small beer, however, compared with any move to write the country's first constitution.

What happens next?

Britain is not going to get the ground-breaking document any time in the near future. Mr Straw said any attempt to encapsulate Britain's constitutional arrangements in a single document should be done on a "bipartisan, consensual" basis over a period as long as 20 years. He also said a national referendum would have to be held to approve the document if it ushered in significant changes.

Professor Robert Hazell, the director of the Constitution Unit at University College London, predicted Britain would never get a written constitution. "Constitutions don't get written in cold blood." Nick Herbert, the shadow Justice Secretary, was equally sceptical. "The last thing Britain needs, with 2,000 years of history behind us, is more of New Labour's blind constitutional vandalism," he said.

Do we need a written constitution?

Yes...

* Britain's arcane hotch-potch of freedoms and rights cannot be defended in the 21st century

* It could help citizens clarify their rights and protect themselves against the state

* Most flourishing democracies base their institutions on a written constitution

No...

* The system should not be tampered with as it has served Britain well for centuries

* The practical problems over what to include and leave out would be a logistical nightmare

* It could undermine the power of Parliament to scrutinise ministers on behalf of the public

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments