The Big Question: What would Scottish independence mean, and how would it work?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

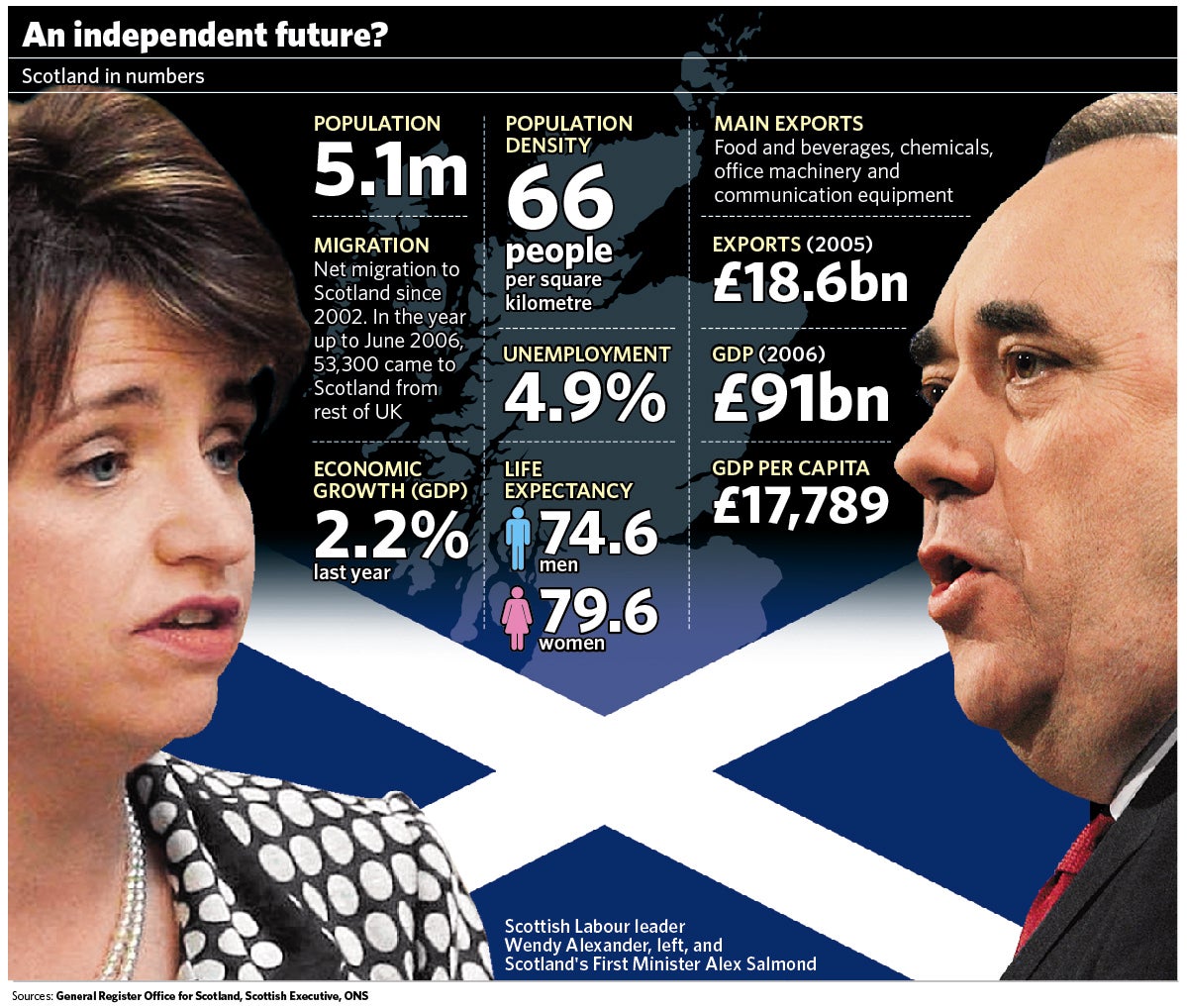

Wendy Alexander, who leads the Labour Party north of the border, has startled a lot of her political colleagues – not least, Gordon Brown – by suddenly announcing that she wants a referendum on Scottish independence, and she wants it now. "I don't fear the verdict of the Scottish people," she said. "Bring it on."

This was a remarkable departure from normal Labour Party policy, which is to preserve the unity of the United Kingdom. Put on the spot, Gordon Brown avoided saying whether he agreed or disagreed, by pretending she had not said what she said.

But this is a disagreement about tactics, not about policy. Wendy Alexander does not want Scotland to leave the UK. On the contrary, she is gambling that if asked now, the Scots would say no. The call for an early referendum was meant to wrongfoot the Scottish Nationalist Party, who run Scotland's devolved administration. They also say they want a referendum, but not until 2010.

What would happen if there was a yes vote for independence?

The SNP, the only party ever likely to organise a referendum, say that if there was a yes vote, they would open negotiations with London about the details, and pass a bill guaranteeing citizens' rights in an independent Scotland, which would no doubt be based on European law. The negotiations would be long and complex, because the peaceful splitting in two of a sovereign country is a rare event in history. The nearest precedent would be break up of what used to be Czechoslovakia.

British citizens would presumably be given time to choose which nationality they wanted to retain. This would be a difficult one for Scots who live and work in England, but have kept up their ties with Scotland – like Gordon Brown, for instance.

Everyone would need a new passport over time, but if the split was amicable, you might not be required to produce it at the Scottish-English border. Scotland would apply and probably be granted membership of the EU, whereupon it would abandon sterling and adopt the euro, so anyone travelling between the two countries would have to change currency.

If the Scots were in sentimental mood, they might retain the monarchy – which after all predates the 1707 Act of Union – but north of the border the Queen would be simply Queen Elizabeth, not Elizabeth II, and her grandson, if crowned, would be William II in Scotland and William V in England.

Would England be better off without Scotland?

The Act of Union in 1707 set off a wave of anti-Scottish sentiment in England, which has threatened to creep back since the creation of the Scottish Parliament and the electoral success of the SNP. An ICM poll for the Sunday Telegraph in November 2006 produced the startling finding that 59 per cent of English voters wish Scotland would leave the UK.

The reason is that Scotland is perceived to be living well off English taxes. New figures throwing light on this issue will be published next month. For now, we can only go on the published figures for the year 2003-04, when public spending in Scotland was £7,346 per head of population, compared with £5,940 in England. Scotland received £3bn more from the Exchequer than it paid in taxes. Scotland is seen as a country that gets Scandinavian levels of public services on US-level taxes.

For Conservatives, another argument in favour of a split is that it would vastly improve the Tories' chances of winning general elections in England.

Would Scotland be better off without England?

The SNP has two answers to the accusation that Scotland lives off English subsidies. One is that a self-governing Scotland could manage its economy better, attracting EU support and joining an "arc of prosperity" with its near neighbours, Norway, Denmark and Iceland.

The other answer is oil. In the past 30 years, taxes from North Sea oil have amounted to about £200bn, at today's prices. Last year's receipts were around £8bn, and this year's will be higher, possibly up to £12.5 bn. That looks like enough to fill the gap between income and expenditure – but it assumes that an English government would roll over and concede that all tax revenues from oil belong to Scotland. Actually, London would fight for a share. And North Sea oil is a diminishing asset. Production peaked at 2.9m barrels a day in 1999, and by 2010 is expected to be down to a million barrels a day – barely a third of what it used to be. If the Scots want exclusive use of the taxes generated by "their" oil, they have left it too late.

Is independence likely to happen?

It seems very likely that there will be a referendum in Scotland in 2010 or soon afterwards, because the SNP have promised it, and there is no indication yet that they are going to lose their position as the largest party in the Scottish Parliament. But even if it happens, and it produces the result the SNP want, it does not follow that Scotland will get independence. The London government would be morally obliged to abide by a properly run plebiscite that clearly showed a majority for independence – but it might not be that clear cut.

What are the possible scenarios?

The turn-out might be very small, or the majority very narrow, and there is an as yet unresolved dispute about what question to put on the ballot paper. If, as the SNP want, it is a vaguely worded question about the desirability of taking further steps towards independence, the London government might interpret that to mean nothing much. If the Scots tried to declare independence in defiance of the Westminster, they would get no recognition internationally.

What are the polls saying?

The evidence is that the Scots are happy to have an SNP administration in a devolved Edinburgh Parliament, but are not minded to vote for outright independence. The opinion polls do not all agree, but they seem to suggest that enthusiasm for self rule has cooled since the SNP won control of the Scottish administration. The Sunday Telegraph poll in 2006 said that 52 per cent of Scots wanted independence; a YouGov poll conducted in the past week put the figure at only 25 per cent, with 59 per cent saying they prefer things as they are. But in 2010, there could be a Conservative government in London, supported by less than a quarter of Scottish voters, which could stoke up separatist sentiment – and that, no doubt, was what Wendy Alexander was thinking when she said: "Bring it on".

Should England and Scotland separate?

Yes...

* Scotland's half-way status, partly independent, partly not, is an anomaly that cannot last

* There are smaller and much less wealthy countries than Scotland now in the EU

* Scotland's economy would benefit from the discipline of self-government

No...

* Most Scots like devolution, but that does not mean they want independence

* Breaking up the United Kingdom would leave each component weakened internationally

* Since 1707, both countries have benefited from the freedom with which people cross the border

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments