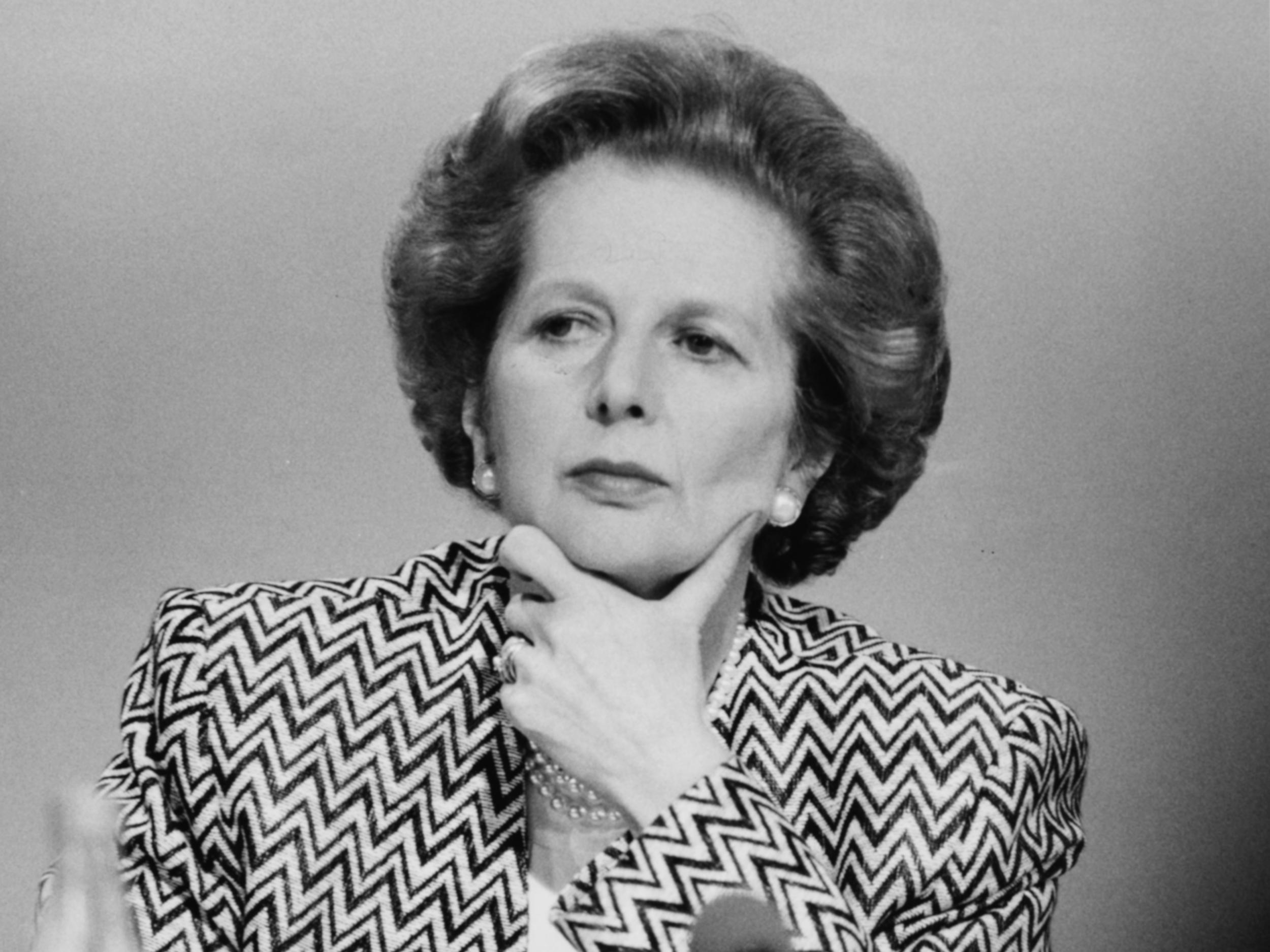

Section 28: What was Margaret Thatcher's controversial law and how did it affect the lives of LGBT+ people?

Reviled clause that banned discussion of same-sex relationships in schools left damaging legacy that still endures

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today marks 30 years since Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government introduced its highly controversial Section 28 legislation.

The clause, part of the Local Government Act 1988, banned the "promotion" of homosexuality by local authorities and in Britain's schools.

A successor to the Local Government Act 1986 (Amendment) Bill introduced by the Earl of Halsbury that had pushed the same agenda, the clause meant in practice that teachers were prohibited from discussing even the possibility of same-sex relationships with students.

Councils were meanwhile forbidden from stocking libraries with literature or films that contained gay or lesbian themes, forcing young people to look elsewhere for educational material, finding solace in novels like Jeanette Winterson's Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985) and the positive examples set by the era's "out" or androgynous pop stars.

Thatcher's law was met with uproar from LGBT+ activists. Three lesbian protesters abseiled from the public gallery of the House of Lords to the chamber before being hustled away by attendants, a spectacular sight that made national news and helped draw attention to their cause. Their actions were commemorated last year when an unofficial blue plaque was placed at Parliament by a group calling themselves the Sexual Avengers.

Activists also stormed the BBC on 23 May 1988, handcuffing themselves to a TV camera and disrupting a broadcast of The Six O'Clock News presented by Sue Lawley and Nicholas Witchell.

In Manchester, more than 20,000 people marched against Section 28 while the actor Ian McKellen came out publicly for the first time in order to voice his opposition.

Ms Thatcher, responsible for the first new homophobic law to be introduced in a century, had voiced her opposition to gay rights at the 1987 Conservative Party Conference in Blackpool.

"Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay," she said.

"All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life. Yes, cheated."

She was emboldened to express her prejudice by a rise in homophobia exacerbated by the AIDS/HIV crisis and its hostile coverage in the right-wing tabloid press.

The Tories capitalised on this sentiment in that same year's election campaign, suggesting that Labour was intent on seeing pro-LGBT+ books taught in school, a powerful piece of rhetoric at a time when the 75 per cent of the population believed homosexuality was "always or mostly wrong", according to a contemporary British Social Attitudes survey.

Section 28 marked a disturbing backwards step for tolerance and inclusivity after the strides made by the British LGBT+ movement since the decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1967, a surge of progress that had seen activists forge alliances with Labour unions and the National Union of Mineworkers, as depicted in the film Pride (2014), and the election of Margaret Roff, Britain's first "out" lesbian mayor, in Manchester in 1985.

The pernicious influence of the clause unquestionably played a huge role in legitimising hate and reinforcing playground homophobia and bullying, demonising LGBT+ children and ensuring many stayed imprisoned in the closet for fear of social reprisals or disapproval.

The clause endured until it was repealed in Scotland on 21 June 2001 and in the rest of the UK on 18 November 2003.

Tory leader and later PM David Cameron apologised for Section 28 as a "mistake" on 1 July 2009.

Its timely passing arguably represented a watershed moment for LGBT+ rights in Britain and marked progress has since been made, a process facilitated by the emergence of Twitter as a platform for cultivating more sensitive attitudes towards questions of representation and diversity.

The number of LGBT+ teachers rose from 5 per cent to 9 per cent between 2014 and 2018, according to new data from Teach First, with many motivated in their choice of career explicitly because of their own experiences as children being unable to address their sexuality in the classroom.

However, as Stonewall has pointed out, the damaging legacy of Section 28 remains and just 13 per cent of pupils say they have been taught about how to be part of a healthy same-sex relationship in the classroom.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments