How could Scotland secure a second independence referendum?

Politics Explained: Row reflects growing threat to the union from a no-deal Brexit

While many MPs are on their sun loungers, studiously avoiding their phones, John McDonnell has taken it upon himself to make news.

In an interview at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the shadow chancellor declared that Labour would not block a second referendum on Scottish independence.

McDonnell also provocatively referred to Westminster as the “English parliament” – a phrase used by advocates of independence to express the view that Scotland is ruled by England.

The intervention sparked a furious backlash as his views directly contradict those of Scottish Labour leader Richard Leonard and the party’s policy north of the border.

McDonnell is regarded as a clever and careful politician who rarely says anything he does not mean, so his comments have triggered fevered speculation that Labour could be eyeing some sort of pact with the SNP.

But why is Scottish independence in the headlines again?

The short answer is because of Boris Johnson’s arrival in Downing Street, shifting the government’s Brexit stance towards a no-deal departure.

Mr Johnson has tried to put the preservation of the UK at the heart of his premiership, by visiting the devolved governments early and by describing himself as “minister for the union”.

However, his visit to Edinburgh, where he was booed and jeered by protesters, seems to have done more harm than good.

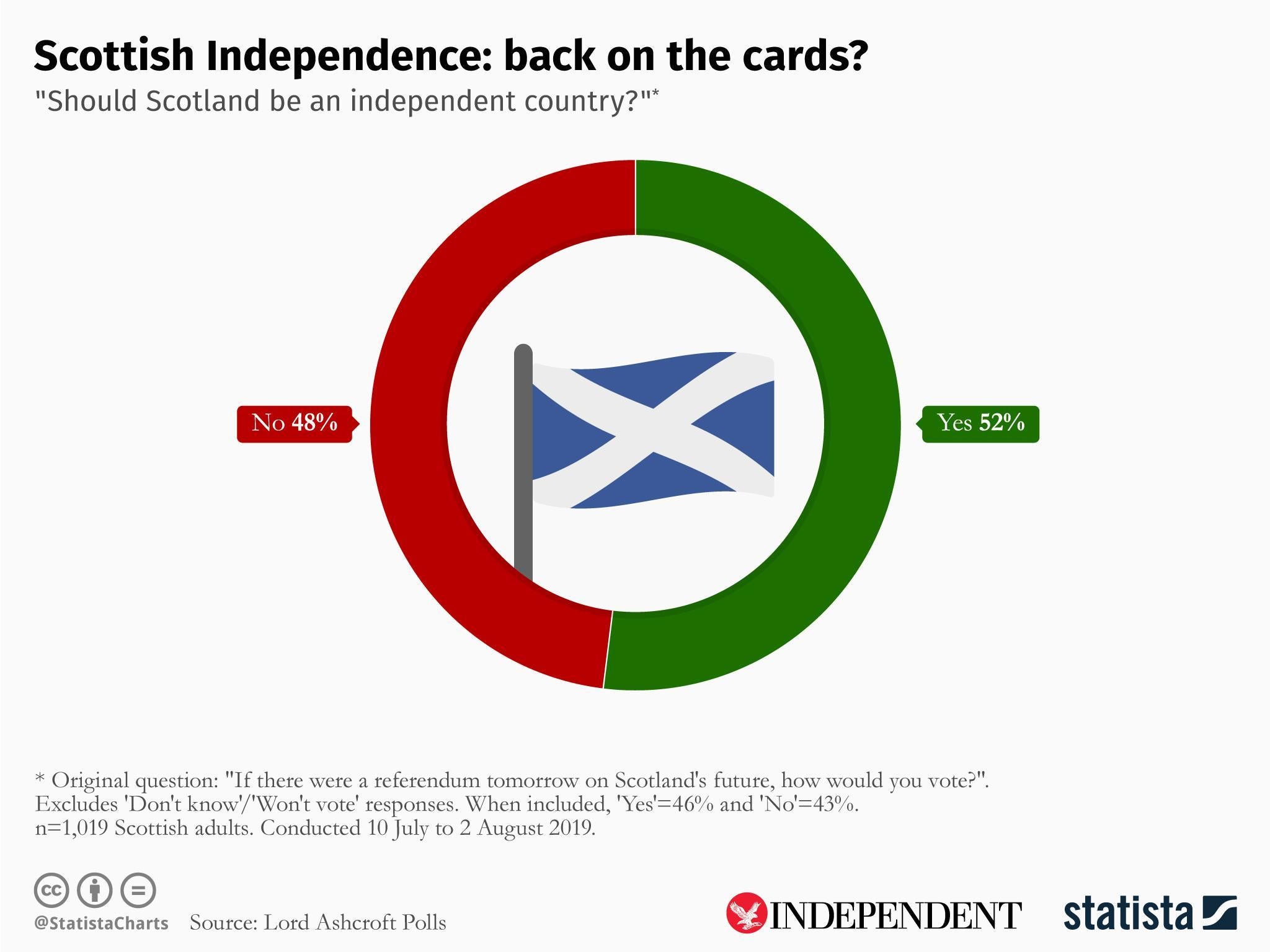

A shock poll, conducted in the wake of his trip, put backing for Scottish independence at 46 per cent, with 43 per cent of voters against.

Support for independence rose to 52 per cent, with 48 per cent against, when those who said they did not know how they would vote or said they would not vote were removed.

The poll by Lord Ashcroft – the first to show a lead for Scottish independence since 2017 – had a major impact.

Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish first minister, said it delivered a “phenomenal” boost for the independence movement, as Scotland was “dragged towards a no-deal Brexit”.

While it is only one poll, the Ashcroft findings illustrate the growing threat to the union from a no-deal Brexit.

By law, Scotland must seek the UK government’s approval to hold another referendum, as matters relating to the union of the United Kingdom are referred to Westminster.

After the 2014 vote, Sturgeon kept her troops at the top of the hill for some time.

She eventually requested consent from Theresa May in March 2017, the day before the then-prime minister fired the starting gun on the Brexit process.

May blocked the move, saying it was “not the time” for more constitutional upheaval. Sturgeon tried again in April 2019 but the request was again denied.

In May, the Scottish government published a bill laying out the framework for a second independence referendum once it has been granted powers by Westminster.

Using a similar framework to previous referendums, the bill would allow a new vote quickly as Holyrood would not need to pass another law. The question and the date would need parliamentary approval under the plan.

If the referendum question were the same as in the 2014 poll, there would be no need for further testing by the Electoral Commission.

There is a small majority for independence in the Scottish parliament, as the Scottish Greens would join the SNP to form a 68-strong bloc in the 129-seat parliament.

All of the remaining Holyrood parties are opposed to Scotland leaving the UK.

The problem for Sturgeon is all her preparations hinge on getting the nod from Westminster – and that remains an unlikely prospect.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments