Richest people in UK have grown even richer over past two decades, new research confirms

Including capital gains alongside income shows a clearer picture of rising inequality, with the total share of remuneration of the top 1 per cent increasing from 14 per cent of the total to 17 per cent over the past two decades

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The richest people in the UK have been getting richer faster than previously thought according to new research which includes the capital gains enjoyed by those at the top.

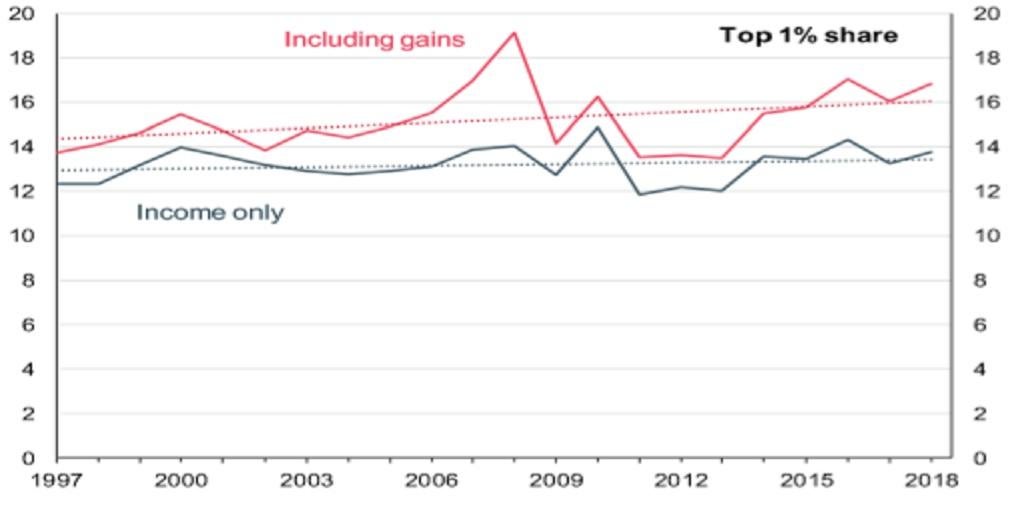

Most measures of inequality only include cash income and show the pre-tax total income share of the top 1 per cent – around 500,000 people – has remained broadly steady at around 14 per cent since the late 1990s.

Some have used those figures to argue that concerns about rising inequality as the very top are overblown.

But new work by Arun Advani of the CAGE Research Centre at Warwick University, Andy Summers of the London School of Economics and Adam Corlett of the Resolution Foundation, using newly available tax data from HMRC, combines these raw income figures with the capital gains of those on high incomes.

Their work shows a clearer picture of rising inequality, with the total share of remuneration of the top 1 per cent increasing from 14 per cent of the total to 17 per cent over the past two decades.

Capital gains accrue when people sell an asset, which can be anything from an entire business to stocks and shares, for more than they paid for it.

The adjustment to include capital gains in measures of inequality is important because the researchers’ work also shows that very wealthiest increasingly take their remuneration in this form, rather than salaries or bonuses.

Private equity partners are well-known for taking the bulk of their remuneration in the form of so-called “carried interest” on their investment portfolios of business because it means they pay a lower rate of tax.

The UK capital gains tax rate is 20 per cent versus 45 per cent for the highest rate of income tax.

In 2017-18, £55bn of taxable capital gains were recorded – more than double the amount recorded just five years earlier

“A clear majority of gains…come from business activity rather than from passive investment and so often reflect a choice to receive remuneration in the form of gains rather than wages,” the researchers say.

Rising inequality when capital gains is included

Within the top 1 per cent, the pattern of rising inequality is even more pronounced, the researchers found, with the total share of the top 0.1 per cent rising from 6 to 8 per cent and the share of the top 0.01 per cent increasing from 2 to 3.5 per cent.

The average total remuneration of those in the top 0.1 per cent – around 5,000 people – has increased from £4.9m to £8.4m since 1997.

Adam Corlett of Resolution said that the data, which goes up to 2017-18, suggested a taxation policy agenda for after the Covid-19 crisis has passed.

“We now know that the top 1 per cent are even richer than we previously thought – and account for £1 of every £6 of taxable income received, while the income share of the top 0.1 per cent has actually grown almost 50 per cent faster than we thought,” he said.

“That scale of inequality should be addressed in post-pandemic Britain.”

Dr Advani said the data should also prompt a reassessment of the impact of the post-2010 austerity years and the claims of various Conservative ministers that it had not increased inequality.

“Official statistics on the impact of austerity suggest that everyone was ‘in the same boat.’ But our report reveals this is simply not the case,” says Dr Advani.

“When you take into account income from capital gains the top one per cent has in fact been doing rather well and inequality has been rising.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments