RBS chief's huge pension 'contrary to bank policy'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

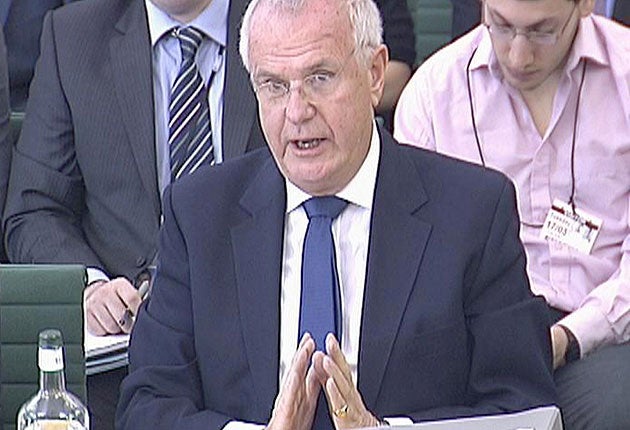

Your support makes all the difference.The £700,000-a-year pension paid out to ousted Royal Bank of Scotland chief Sir Fred Goodwin was "clearly contrary" to the bank's own pension policy, City Minister Lord Myners told MPs today.

Lord Myners refused to apologise for allowing the massive payout to go ahead, insisting he was not told "the full story" by the RBS board and did not learn that it had chosen to double Sir Fred's pension pot until four months later.

He told the House of Commons Treasury Committee that it was "beyond my comprehension" that the RBS board had agreed to allow Sir Fred to take his full pension from the age of 50 - something which effectively doubled its value from £8m to £16m.

RBS's own pension policies said this arrangement was available only to employees voluntarily retiring early, while it was clear that Sir Fred - who has been widely blamed for the bank's multibillion-pound losses - could not turn down their request for him to go.

The board "consistently misdirected themselves" about Sir Fred's entitlement, even after being warned by a leading consulting firm that it would have adverse consequences, Lord Myners told the committee.

The size of Sir Fred's pension sparked furore when it became known earlier this year and was branded unacceptable by Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who took legal advice on whether any of the money could be clawed back.

John McFall, the chairman of the Treasury Committee, which is carrying out an inquiry into the banking crisis, asked Lord Myners: "Isn't it the case that you have dropped the ball? Detail is king and you haven't looked at it and you were either negligent or misled - it can only be one or the other."

Lord Myners said he discussed the issue of Sir Fred's pension with members of the RBS board when they informed him on October 11 last year that he was to be replaced.

Working from a script he had drawn up for discussions with banks where the Government was taking a major stake, he said he was "very clear" that ministers did not expect banks to abrogate contractual commitments, but expected there to be no rewards for failure, that pensions to departing executives should be "minimised" and that executives should be required to mitigate loss-of-office cost wherever possible.

He said director Robert Scott told him: "The pension will be enormous, you know that."

But he insisted that neither Mr Scott nor the then chairman of RBS, Sir Tom McKillop, informed him that the board intended to exercise its discretion to allow Sir Fred to draw his full pension at the age of 50.

"At no stage prior to February of this year was I or anyone else in the Government, so far as I know, made aware that, in the process of replacing Sir Fred Goodwin, RBS had exercised the discretion which allowed him to take his full undiscounted pension from the age of 50 and thereby nearly doubled the value of his pension," said Lord Myners. "Quite the contrary."

Sir Tom and Mr Scott "expressed no issue at all" about the principles which he set out in relation to the departure of senior staff "although it has subsequently become clear that they were already embarked on a process which was contrary to those principles", said Lord Myners.

"It is beyond my comprehension that RBS could have then exercised a discretion that very substantially increased the cost of funding Sir Fred Goodwin's pension," he said.

RBS policy entitled staff who were asked to retire early to receive their full pension early if they voluntarily took up the offer, said Lord Myners.

But he added: "Sir Fred Goodwin didn't have the option of staying. The board had decided he must go.

"Someone in RBS took the decision to treat him more favourably than was required. This decision was completely at odds with the principles that the Government made clear to RBS and expected them to follow."

And Lord Myners said: "When directors fail to act in the interests of shareholders, they should be held to account. It is not the job of a Government minister to negotiate or settle the details of individual transactions the banks enter into, including termination agreements for departing executives.

"I didn't negotiate, settle or approve Sir Fred Goodwin's departure terms. All those issues were handled by RBS.

"The new board of RBS, like the Government, is very concerned to understand exactly how people in the company could have made this quite extraordinary decision, clearly at odds with the principles the Government had laid out, and exactly who made that decision - a decision which was also clearly contrary to the terms of reference of the remuneration committee of RBS."

Papers submitted by the RBS board to the company's remuneration committee made clear that "they consistently misdirected themselves in saying that Sir Fred's pension reflected his contractual entitlements", said Lord Myners.

"It simply did not reflect his contractual entitlements, only the interpretation that they had allowed to be placed on it by virtue of the fact that they had requested that he retire, rather than them requiring that he retire - which was clearly, in my view, what they had actually done.

"In order that he could get a better pension, they framed this in terms of a request, but I repeat my view that it was a request that clearly Sir Fred was not going to be able to decline.

"They were advised very seriously by Watson Wyatt - a reputable firm in this area - that this would have adverse consequences and shareholders would not approve of this decision but they continued with their actions.

"It is the board to whom these questions should be directed, not a minister."

Lord Myners said his discussions about Sir Fred's pension took place during a weekend when he was working "round the clock" on the Government's bail-out of a number of struggling banks and acknowledged that there was "a limit to how much we could do" in relation to the details of the package.

But he added: "What is clear with hindsight is that I was not told the full story."

Lord Myners faced a barrage of hostile questions from MPs on the committee of all parties.

Senior Tory Michael Fallon told him: "Either you were party to some very expensive piece of back-scratching and it was only later, when the Prime Minister found out about it, that you pretended that you hadn't approved the full details, or you simply failed in your duty to the taxpayer."

Lord Myners, however, insisted that he had taken no part in the decisions about Sir Fred's pensions which were made by the RBS board.

"I made no decision, my approval was not sought, I was given no information, I sought no information. What I did do was to set out very clearly the principles," he said.

"The responsibility for fully informing me on these matters lay with Sir Tom Killop and Mr Bob Scott."

Lord Myners said it was clear that the RBS directors took their decision on Sir Fred's pension without a "single point of data" on the costs.

He said they had even given Sir Fred the choice of taking his full pension at the age of 60 or at 50.

"I think one would have had to have been a monkey in that situation to have spent a great of deal of time deciding which of those choices to take," he said.

"But it does give a picture of a board of directors - or at least some directors - bending over backwards to be generous to Sir Fred."

He said there was "a real sense of denial" within RBS about the extent of the failures, with Mr Scott warning that, if Sir Tom was forced out, the non-executive directors would resign in protest at his "harsh and outrageous treatment".

Lord Myners said it would have been straightforward for the RBS board to have dismissed Sir Fred with 12 months' salary as compensation, and a duty on him to find alternative employment as soon as possible, in which case the RBS payments to him would have ceased.

"It would have been a quite straightforward and simple thing to have done," said Lord Myners.

"The board could quite easily have concluded that the conduct of a man who has taken his bank towards a reported loss of £30bn probably met the test of no longer enjoying the confidence of the owners of the business and the board of directors.

"And in those circumstances they could simply have terminated his contract."

Lord Myners said he accepted it was "a challenge" for regulators to keep up with complex trades but added: "I believe that relief is at hand because these activities were clearly nothing like as profitable as originally believed."

He said such activities would become less prominent in the future if regulators required more capital to be held against them.

"Banking will become much simpler," he said.

But he stressed: "Banks have suffered huge losses from very straightforward banking."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments