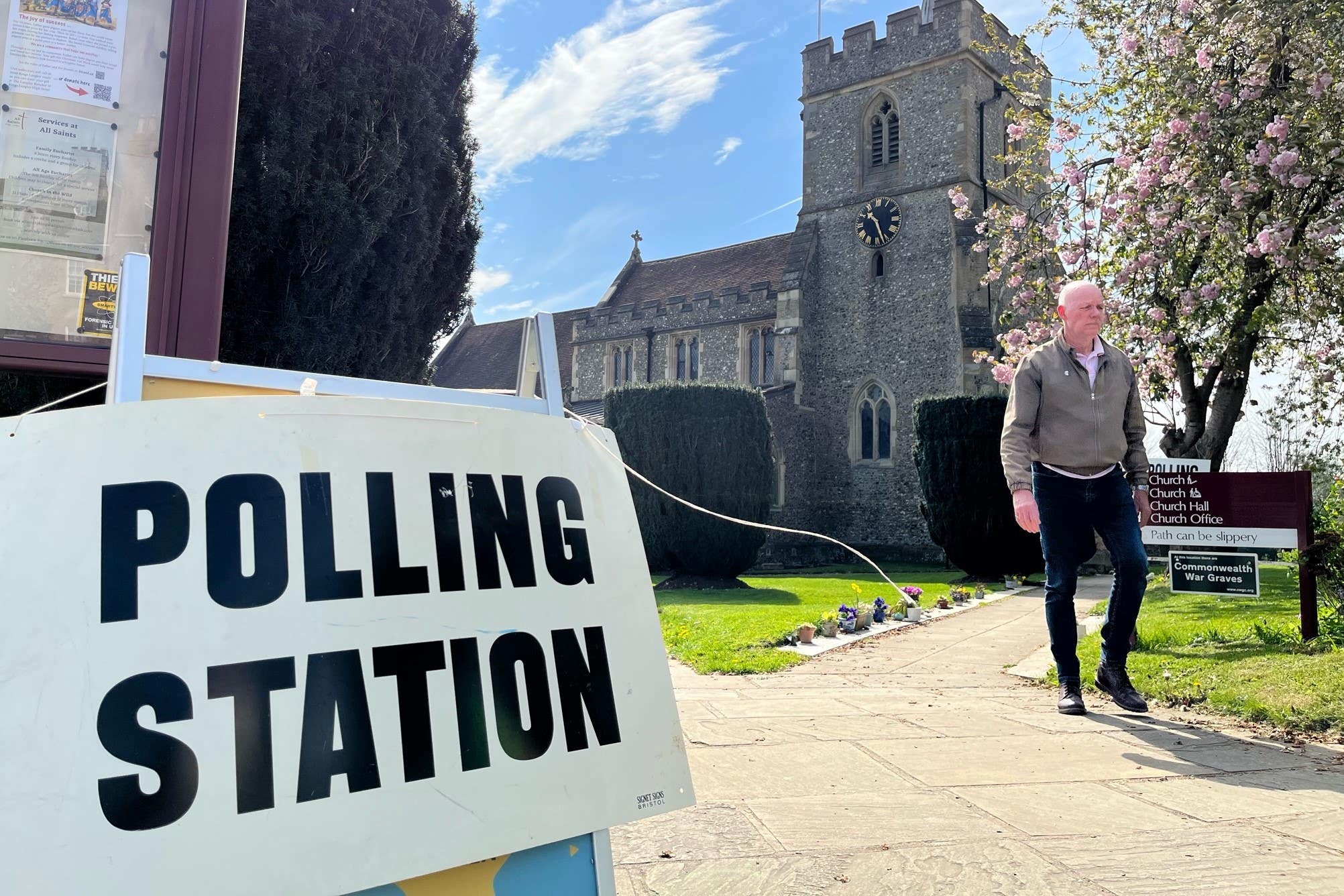

Why are the Conservatives extending voter ID laws?

There’s scant evidence that new restrictions on proxy and postal voting will ‘protect the integrity of our democracy’, says Sean O’Grady – and may even give the Tories a small electoral advantage

Compulsory voter photo ID is to be extended to postal and proxy voting, the government has decided. It follows the controversy over photo ID for in-person voting in the last round of local elections, and accusations that the Conservatives were seeking a partisan advantage. Some returning officers have confirmed that a number of voters were deterred by the new rules, while more may not have bothered to make the journey at all.

New requirements will apply to UK parliamentary elections and other reserved elections, referendums and recall petitions. Local elections in Scotland, and local elections in Wales apart from police and crime commissioner elections, are devolved, and thus not in scope.

Why is the government doing this?

Of all the problems facing the nation, fixing unbroken elections seems the least urgent. If such reforms are to be made, and the system does evolve, they are surely best done on a cross-party, consensual basis to avoid allegations of vote-rigging and gerrymandering. The Trump experience in the US shows what can befall a nation where faith in the electoral system is cynically eroded by sore losers. The Tories rejected cross-party amendments suggested by the House of Lords; predictably, the new rules are viewed with suspicion by opposition parties and many voters.

Was this not in the Tory manifesto, then?

Not entirely. A written statement from Dehenna Davison announcing the move states that it is part of the government’s manifesto commitment “to protect the integrity of our democracy”. However, that is only partly correct; there was no mention in the 2019 manifesto of requiring photographic identification, only some form of ID. “We will protect the integrity of our democracy, by introducing identification to vote at polling stations, stopping postal vote harvesting and measures to prevent any foreign interference in elections.”

Will the Conservatives win an unfair electoral advantage as a result?

Perhaps not from this move. As Jacob Rees-Mogg suggested the other day, the practical effect of reducing the number of older people and people in poorer areas from voting in the local elections may even have hurt the Conservatives more than their opponents, given the radical change in the profile of the Tory vote in recent years – even older and more working class than historically was the case. Rees-Mogg admitted the attempted gerrymandering had failed. Making it even harder for older and more infirm voters might have the same inadvertent effect under the new restrictions on proxy and, especially, postal voting.

Aside from that, the Tories might gain a small benefit from using this issue as a dog whistle – exploiting the occasional high-profile incidence of postal vote fraud in places such as Tower Hamlets and West Yorkshire, albeit still relatively minor and restricted to local not Westminster elections.

Where the Tories will almost certainly gain an unequivocal, if small advantage is in the extension of the franchise to expats. The old qualification that they should have lived in Britain no more than 15 years ago has been abolished, which means people who haven’t set foot in the UK since, perhaps, the 1950s will be able to vote on the same basis as residents. Indeed, the absent expat voter will potentially be able to make their vote count for more in practice if they can make it valid in a highly marginal constituency. In seats where a few dozen votes will make the difference, the expat vote is conceivably crucial.

Are there any other objections?

Bethany Bale, from Disability Rights UK, said the changes will “make voting harder for disabled people”. which seems a reasonable assumption. Generally, the more difficult it is to vote, the more it impacts poorer and ethnic minority voters; it is indirectly discriminatory in its impact.

What do other countries do?

A requirement for photo ID for voting has been in place in Northern Ireland for some time, where personation was a problem. Across the democratic world, voter ID is not uncommon, but demanding photo ID is less widespread. Many other European countries have compulsory ID cards, traditionally anathema to the British way of life. Indeed, when the Blair government was contemplating an ID card system, Boris Johnson wrote: “If I am ever asked on the streets of London, or in any other venue, public or private, to produce my ID card as evidence that I am who I say I am, when I have done nothing wrong and am simply ambling along and breathing God’s fresh air like any other freeborn Englishman, then I will take that card out of my wallet and physically eat it in the presence of whatever emanation of the state has demanded I produce it.”

Times change.

Will the new regulations be in place before the next general election?

Barring any unexpected rebellions, the change doesn’t require primary legislation and can be implemented by a Statutory Instrument with a simple vote of approval. That shouldn’t take long.

However, as with the changes made before the local elections it will add to the burdens on local councils if they have to re-register postal and proxy voting mandates. The government says it will make life easy for election registration officers by digitising the procedure, which does tend to need a lot of paperwork. However, and ominously, Davison’s statement says: “The online service is currently being built and will be tested to ensure it is robust and accessible for electors.” What are the chances it will be up and running properly by, say, autumn 2024?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments