How long can we expect strikes to continue?

Extended action carries risk for the unions and government alike, writes Sean O’Grady

The Royal College of Nurses (RCN) has announced an extension of their industrial action in England to hospital A&E departments, cancer units and critical care. On top of that, their strikes, starting on 1 March, will be over 48-hour periods, thus covering night shifts as well. It is an escalation that may define the outcome of the dispute.

What’s going to happen?

The headline news is that, aside from some sort of public service strike being scheduled for somewhere in the UK every day for the foreseeable future, on 1 March, from 6am, nurses at more than 120 NHS employers in England will begin action, which for the first time will last 48 hours. This is a significant move, and one loaded with risk for patients, the unions and the government alike.

Is the public still backing the strikers?

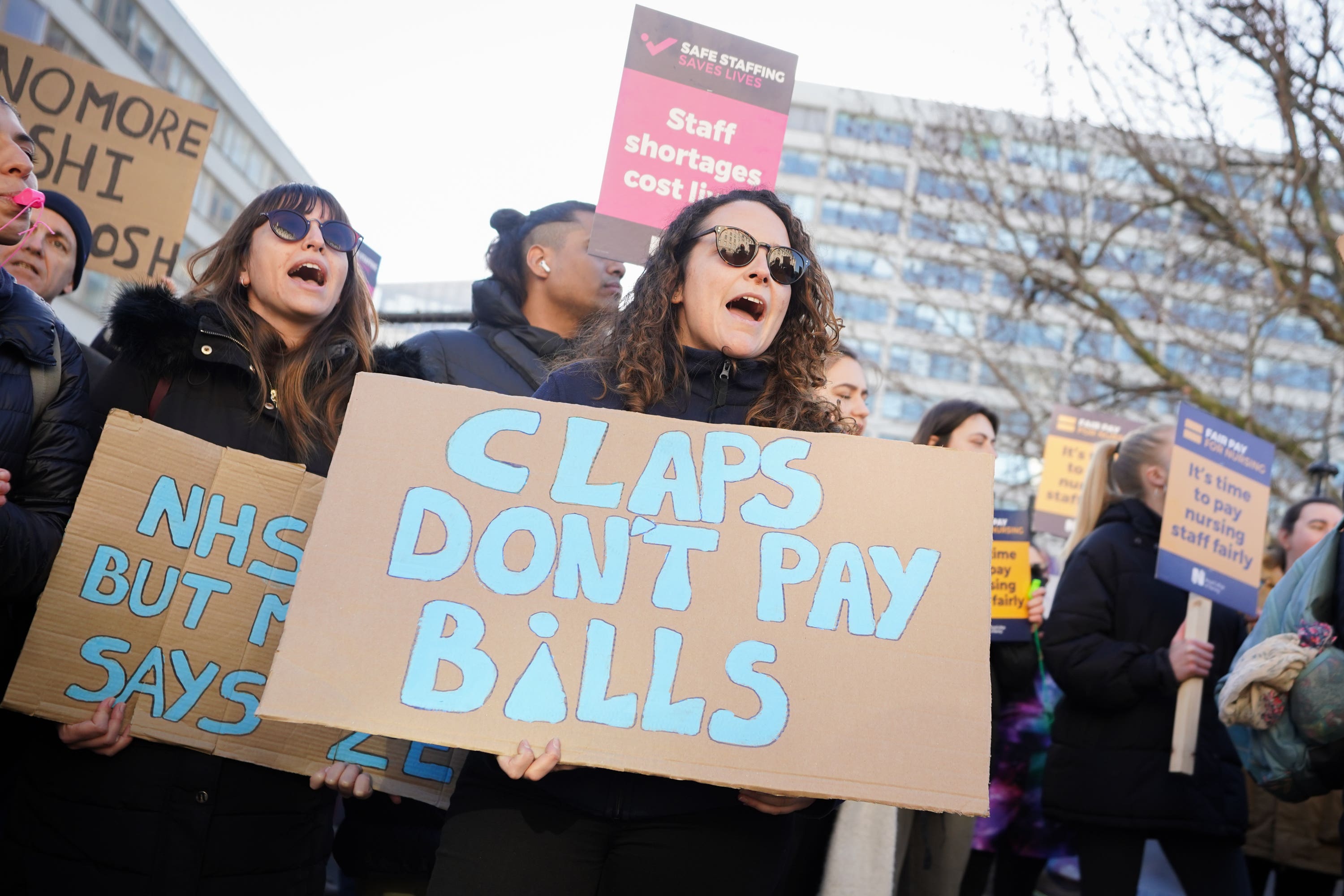

Yes, but it varies with the profession of those taking action, and support has been slipping. The nurses we clapped for not so long ago are favoured; Mick Lynch and the rail strikers of the RMT less so. A critical question is how public sentiment will shift as the strikes become more than a mere inconvenience and even begin to cost lives. It’s difficult to see how a legal and moral obligation to protect “life and limb” can be honoured if, say, ambulances and A&E units are subject to strike action simultaneously. At some point, people may feel that things have gone too far.

Why can’t they just settle the strikes now?

Good question. To state the obvious, because both sides think they can win and it’s worth going through the ordeal. For the nurses, and other strikers, the effort involves a real personal financial sacrifice, because their employers don’t have to pay them wages on a strike day. That in itself suggests that they are taking action for other reasons as well as pay – understaffing, an inability to provide a high standard of care, and general overstretch. It does actually look as though they have no alternative but to take this action, and force the changes needed to keep the NHS effective and thus save lives.

Who will win?

The government – or at least in the sense that it can afford to spin things out a little longer, and it has calculated that the worse things get in the hospitals, the more public support for the strikes will erode. On the other hand, the strikes are still obviously unpopular, and add to a sense of national malaise and official incompetence; and on balance, voters blame ministers for the mess. Also, the NHS will never clear the pandemic backlog, and Rishi Sunak won’t meet his pledge to cut waiting times, unless the strikes end soon.

So the nurses will eventually get a bigger rise, but they may have to wait, and keep up the pressure – without costing lives.

Could the strikes be settled quickly?

In the case of the nurses, almost certainly. Like wars, all strikes end eventually, and usually with some degree of compromise on all sides. This dispute doesn’t have the same quality as, say, the miners’ strike of 1984 to 85, when the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), led by Arthur Scargill, made little secret of the fact that it wanted to bring down the government (and Margaret Thatcher, who wanted to smash union power). The RCN is not the NUM, and the current industrial action doesn’t have the same political dimension. Equally, the government can’t afford, these days, to further alienate the public by being visibly vindictive towards the nurses.

The “landing ground” for a settlement has been plain for weeks, and certainly since the RCN cut their demand from 19 per cent to 9 per cent. The recommendation of the independent pay review body, to which the government is stubbornly adhering, is for an average 4 per cent rise. So something like 6.5 per cent, plus some reviews of staffing, excessive vacancies and stress levels, would probably settle things rapidly.

The obstacle is probably fear on the part of ministers of setting a precedent, and of weakening the authority of the pay review system, adding to wider upward pressures on wages and thus on labour costs and inflation. They also don’t want to lose face. The most likely outcome is an abnormally large settlement for next year, effectively catching up with what could be conceded immediately. But there will be little real saving for taxpayers. Similar logic applies to varying extents to the other public-sector and quasi-private-sector groups (eg the railway workers).

How long will all this last?

The strikes in the NHS, schools, universities, Border Force, the civil service and the railways will drag on for a few months until inflation subsides, modestly larger pay awards are granted, and more restrictive anti-strike laws start to make their presence felt towards the summer. Private-sector pay awards are running at more than 6 per cent on average – a real-terms cut, but enough to avoid strikes. There will be no general strike, and the government won’t fall. Probably.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments