Tory leadership contest hangs on gamble over the economy

Liz Truss’s dismissal of Bank of England warnings revives memories of Brexit attacks on ‘experts’, writes Andrew Woodcock

The factors that will determine Tory members’ choice of the UK’s next prime minister are various – with perceived competence, likeability, passion for Brexit, readiness to bash “woke” opinion, and ability to beat Labour at the next election all among them.

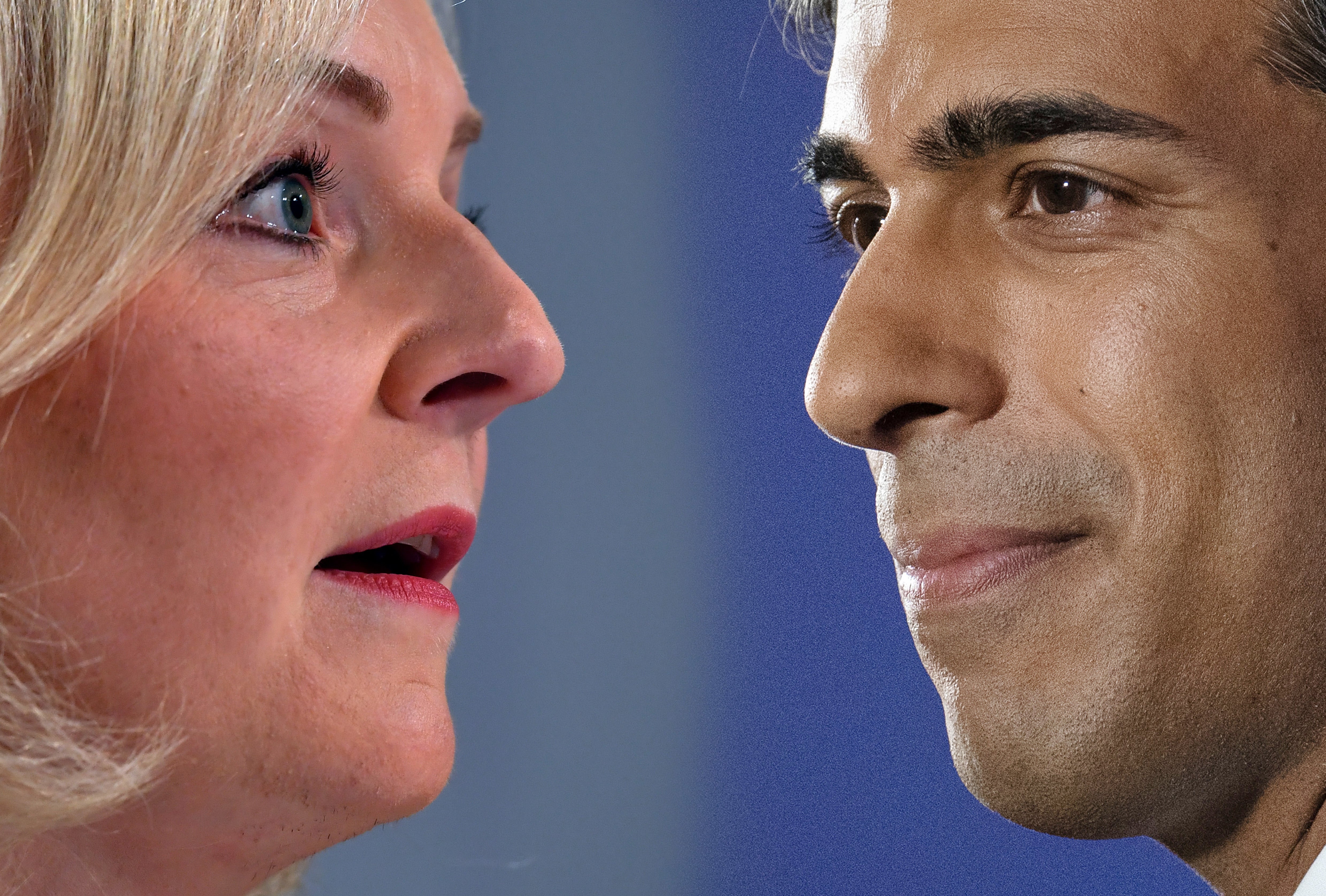

But at the heart of the contest between Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak is a single factor that will potentially have massive consequences for the country – a fundamental split on the economic response to the cost of living crisis.

As has been well-rehearsed in a succession of TV debates and hustings, Truss believes that the answer to the difficulties Britons are facing in paying for essentials is to put a bit more money in their pockets through tax cuts.

Sunak’s retort is that immediate tax cuts would only make matters worse. Giving people more money to spend at a time of supply shortages will force prices up further. Borrowing billions to do so will undermine international confidence in the UK, tank the value of the pound and add to the government’s already astronomical debt repayments.

Other commentators – most recently former CBI president Paul Drechsler – point out that relief from tax cuts will mostly go to more comfortable households and will arrive too late for anyone going hungry and cold this winter.

Even the removal of green levies from energy bills promised by the foreign secretary, while taking some of the pressure off the poor, will disproportionately help the wealthy who use more gas and electricity.

Ms Truss, of course, dismisses the former chancellor’s warnings as “Treasury orthodoxy”, which she implies has played a big part in getting the UK into its current parlous economic condition.

Declaring that it is not possible to “tax our way out of a recession”, she argues that excessive caution about state debt is holding back the growth and productivity improvements needed to deliver prosperity. Giving taxpayers more of their money back will allow more spending, more investment and more innovation, and get the economy sizzling again.

It’s an approach that has sparked alarm among many economists, and which Margaret Thatcher’s chancellor, Nigel Lawson, – a Sunak supporter – believes could usher in a 1970s-style inflationary spiral, at a huge cost to jobs and livelihoods.

Back then, a “dash for growth” announced by chancellor Anthony Barber to invigorate a moribund economy saw taxes slashed and lending eased. It delivered growth in the short term but was followed by ballooning borrowing, a fall in the value in sterling, and runaway inflation, which was not tamed until the mid-1980s after Thatcher – notably – raised taxes in her early years in office.

It is out of such experiences that orthodoxies are built. Economists, given the opportunity to see how a particular policy plays out in the real world, adjust their theories and amend their forecasts in the hope of avoiding similar mistakes in future. Now some revealing remarks by the leadership frontrunner have shone an interesting light on her thinking, highlighting a mindset shared by many of this generation of Tory leaders that would have horrified some of their predecessors in the party.

Presented with the sober analysis of the Bank of England, that the UK is heading for five quarters of negative growth and inflation topping 13 per cent, Ms Truss responded that “forecasts aren’t destiny” and we must not “talk our way into a recession”.

The remarks are all too reminiscent of the Leave campaign’s dismissal of warnings about the impact of Brexit as “Project Fear”, and Michael Gove’s notorious assertion that “people in this country have had enough of experts”. The entire Brexit project was underpinned by senior politicians willing to brush aside the judgment of experts and instead place their faith in their own hunch that things would turn out fine.

Now that their “sunlit uplands” have turned out to involve – as predicted – loss of trade, increases in red tape and queues at borders, they continue trashing the experts by insisting that the downsides are not as bad as the worst forecasts implied.

Of course, economic predictions are often wrong. Economists recognise that fact openly, and usually build into their models a wide range of possible outcomes deviating from their “central forecast” on the positive and negative side. But they represent the best stab, by people in a position to have some chance of getting it right, at answering the unfathomable question: what happens next?

Economic decision-making is always a high-stakes gamble. But if politicians are to write off the orthodoxy espoused by their advisers and dismiss their forecasts as a basis for forming policy, it is important that they make very clear that they are driving the stakes of that gamble even higher.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments