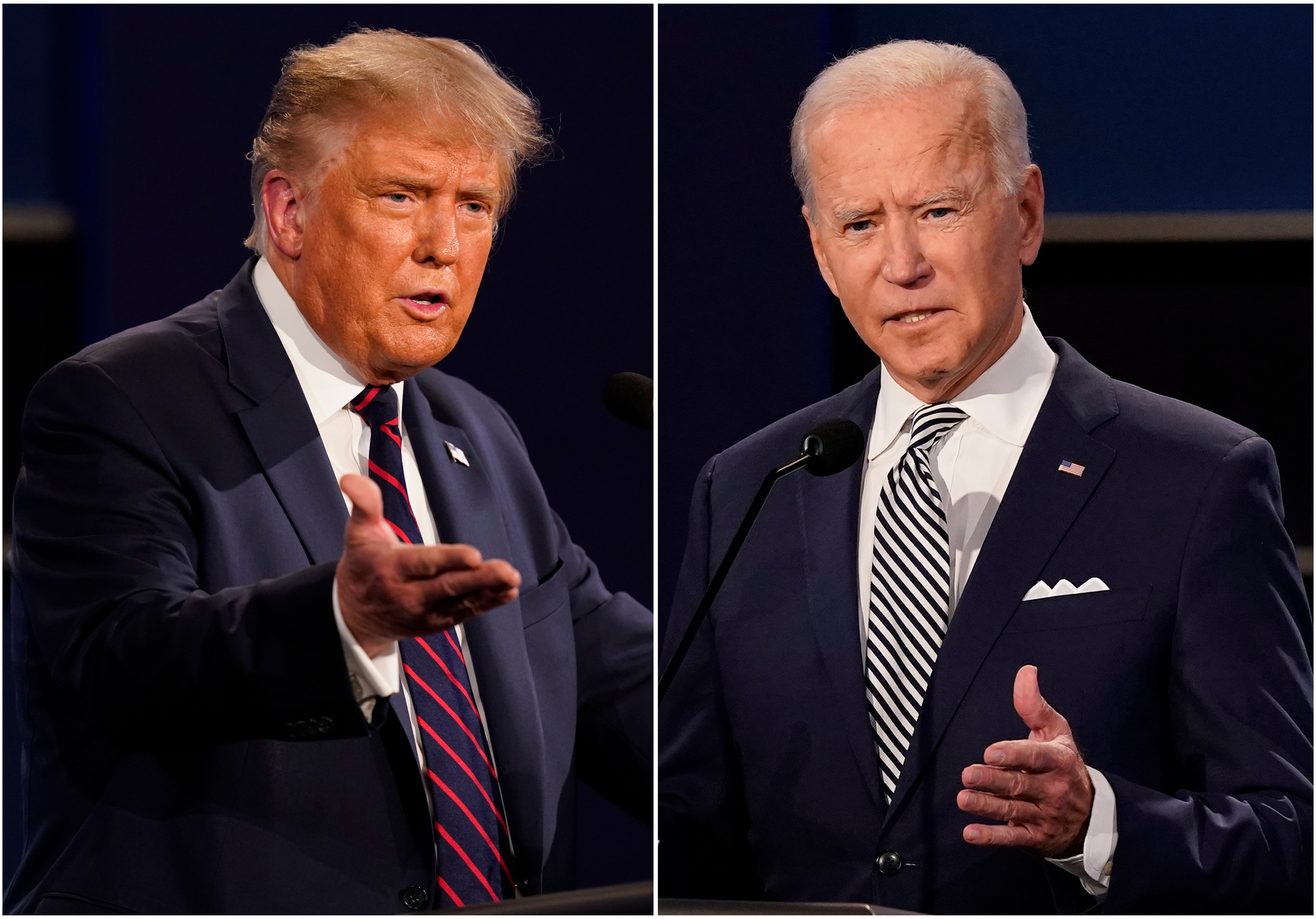

What if the US election polls are wrong?

There is precious little time for Trump to change the trajectory of the election. But, as Sean O’Grady explains, history shows why it’d be foolish to write him off just yet

Joe Biden and his supporters must be looking at the opinion polls and wondering if things might be just a little too good to be true. They may be, for three distinct reasons, all possibly true and – possibly – working to the unlikely advantage of Donald Trump.

First, they could just be wrong. Even as a snapshot of present opinion – because 3 November is, after all in the future – they might be inaccurate for “technical” reasons. As has been the case periodically in general elections, the pollsters’ methodologies move out of kilter with social trends, distorting the results. Thus, for example, polling the same standard target sample of 1,000 people through face-to-face contact (in the street and/or door to door) will miss some people; doing it by phone may miss others; using the internet might well not reach older citizens, and so on. The pollsters’ methods of “weighting” samples by demographics might be out of date, using, say, older census data. They may have failed to notice strong unexpected trends in willingness to turn out to vote, or some other long-established correlation might have uncoupled itself without them fully noticing. In 2016, for example, the state-based polls in places such as Wisconsin, Iowa and Ohio failed to catch the switch to Trump among working-class so-called left-behind voters, both in terms of moving from a Democrat allegiance and/or bothering to go and vote. There may also have been an underestimate of this at the national level, but in the US system of the electoral college and the importance of swing states it became a crucial (if still relatively modest) misreading of public mood.

That brings us to the second factor, which is that a national lead in the polls is, in a sense, irrelevant. To give an absurd example to make the point, President Trump could fail to persuade a single voter in New York and California to back him, because they are already in the Biden column, but would still take the White House if he can scrape a bare majority in Florida, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and the like: where you win votes matters more than how many votes you get. Indeed Hilary Clinton “won” in overall votes in 2016 by 2,868,686 votes (a 2.1 per cent margin) over Trump. By the same token, Al Gore “beat” George W Bush by 543,816 (give or take the odd hanging chad) in the controversial 2000 contest.

Clinton’s failure to campaign in the rust belt swing states in 2016, coupled with possibly inaccurate polling, contributed to the shock felt four years ago. Biden’s current double-digit lead probably overwhelms any state-based effects, but not if the national lead is itself overstated.

In any case it is a curious thing that national polling so dominates coverage of the US election, and so little effort is put into state-based polling, either quantitatively or qualitatively.

Third is the phenomenon known as “late swing”. An example of that would be the 1980 campaign. Although it always looked likely that Republican challenger Ronald Reagan would beat the incumbent Jimmy Carter, there is some feeling that a late change of mind among key voters turned a comparatively competitive election into something of a pushover for Reagan at the end. More pertinent is the dramatic shift to Biden over the past few weeks, a product of the televised debate and the president’s behaviour during and after his brush with Covid-19. Of course it is possible that his recovery, the rallies, an arms control deal with Russia, a Biden gaffe, civil disturbances or some other events could push floating voters back to Trump. None of that could be entirely ruled out.

There is a least one vague historic precedent, apart from the parallels with 2016, that might give Trumpists some heart. Back in 1948 there was another incumbent president, apparently unpopular, facing seemingly certain defeat. The polls put the Democrat president, Harry Truman, between 5 and 15 percentage points behind his challenger, Tom Dewey, Republican governor of New York (when such a thing was possible). Yet Truman went on to win by a shock 4.4 per cent. The pollsters and what’s now called the mainstream media were humiliated, even more than in 2016. So confident was the press about Truman’s demise that they’d all prepared their splash stories on that basis. So cocky was the Chicago Daily Tribune that it went ahead and printed an early edition with the banner headline “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN”. Truman was soon pictured gleefully brandishing the erroneous first edition. He quipped: “That’s not how I heard it!”.

In the event Truman served a further four distinguished years. His surprise victory was all the more remarkable because the Democratic Party split three ways in the election, with progressive and segregationist breakaways. However, shrewd campaigning based on electoral college votes and targeting the votes of people of colour, shortcomings in the pollsters’ techniques and their neglect of last-minute polling in what seemed a foregone conclusion made Truman into a political Lazarus. Donald Trump, who likes to go one better, will be hoping for a Trumanesque second resurrection in 2020.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments